Homeschooling With Movies: Using Hitchcock to Teach Literature

A combination of watchability and intelligence make Hitchcock a great starting point for serious cinema studies — and for applying critical reading techniques to a text that isn’t a book.

When Vertigo premiered 60 years ago this May, Alfred Hitchcock cemented his reputation as one of the 20th century’s great filmmakers. This spring is an ideal time to explore his work with its complex themes of control, identity, and connection.

So many of the things we take for granted in the world of cinema comes from obsessive auteur Alfred Hitchcock: those stomach-twistingly abrupt edits, the unadulterated pleasure of voyeuristic shots, the camera that roves dreamily but inevitably through the landscape, and that eyeline match that pulls the object of desire directly into your gaze. Hitchcock was notoriously difficult: His complex, controlling treatment of women, his micro-focus on every detail, his puppetmaster management of scenes and characters — all of these find their way into his films. But Hitchcock wasn’t just a cinematic genius. His movies also had tremendous popular appeal, spurring film critic Andrew Sarris to say, wryly, that “Hitchcock's reputation has suffered from the fact that he has given audiences more pleasure than is permissible for serious cinema.” That combination of watchability and intelligence make Hitchcock a great starting point for serious cinema studies.

WATCH REAR WINDOW and Talk about the Elements of Suspense.

The film’s protagonist Jeff is stuck in his apartment in a cast, so we’re stuck with him in his claustrophobic housebound perspective. Notice how Hitchcock slowly builds the tension — first, our curiosity is piqued as we watch Jeff ’s neighbor-across- the-way’s suspicious behavior. Then, curiosity turns to fear when we, with Jeff, watch his girlfriend search the apartment. We know, with Jeff, that the man is on his way back, but like Jeff, we’re powerless to warn Lisa. All that suspense builds to a fever pitch after Jeff loses sight of the man and we realize that the villain is coming after chair-bound Jeff. The genius of these scenes lies in Hitchcock’s focus on the narrow perspective of the protagonist: Like Jeff, we’re voyeurs who see more than we bargained for. Hitchcock manipulates us into complicity with Jeff ’s voyeurism — and by extension, his peril. Jeff is our cinematic stand-in — we’re not sure whether he’s imagining a murder to entertain himself or whether he’s truly witnessed something terrible, but that’s because we’re not certain of our own intentions.

Watch NORTH BY NORTHWEST and Talk About Setting the Scene.

One of the most visceral cinematic moments in North by Northwest comes in the middle of nowhere. Cary Grant’s suave businessman finds himself in the middle of a midwestern cornfield, a stark contrast to the busy city where his story begins. There, people and cars are so commonplace that no one notices them, but pay attention to how this changes once the bus drops him at this lonely out- post: Suddenly every car becomes imbued with meaning, promising danger or hope. With the protagonist, we’re screening the long, flat landscape for lurking danger, and like the protagonist, we’re shocked when it appears from the place we least suspect.

Watch VERTIGO and Talk about Psychology as Plot.

Casting Everyman Jimmy Stewart as the lead in Vertigo was a brilliant ploy on Hitchcock’s part: As soon as we see Stewart’s craggy, earnest face, we know we’re looking at the moral center of the movie. This is the guy we’ll cast our lot with. Except, in Vertigo, we’re wrong. We’re expecting Scotty to repair the damage he did at the beginning of the film when his acrophobia caused another police officer’s death or to somehow save the doomed woman whose suicide he couldn’t prevent. Instead, he spirals (just as the movie’s name suggests) further and further into twistier and twistier obsessions. Notice how Stewart’s psychology drives the plot, his obsessions echoing the role of director as he casts, trains, and observes his ice-blond leading lady — just like Hitchcock himself. The film is both a sly nod to Hitchcock’s reputation and a study in obsessive psychology.

Watch PSYCHO and Talk about Surprising the Audience.

Hitchcock’s version of a horror flick changed movies forever. Though countless other movies have followed its unpredictable twists and harrowing notion of purposeless evil, when Hitchcock (spoiler) sent his leading lady to her doom halfway through a perfectly plotted storytelling session, he shook not just the audience but the entire notion of cinematic narrative. Once the main character dies, the audience has no idea what might happen next. The whole idea of a story with a beginning, middle, and end is disrupted when Janet Leigh dies and the movie continues on without her. It’s a sudden, vicious transition that keeps us unsettled for the rest of the film. The film’s double twist, when (spoiler again) the monster is revealed, looking nothing like a Mr. Hyde or Frankenstein’s Monster but surprisingly like any one of us, is as unexpected as everything else—but also surprisingly right. In the post-World War II world, the notion that evil was not an outside force but a force within us is both shocking and utterly appropriate.

Want more? Hitchcock has inspired filmmakers for decades, but these modern movies really channel his spirit.

Source Code (2011): Jake Gyllenhaal stars in this twisty North by Northwest-ish thriller about a man whose

consciousness travels back in time with eight minutes to stop a deadly accident.

Shutter Island (2010): This noir-ish movie captures Hitchcock’s uneasy realities — right down to the (spoilers) twist ending.

Frantic (1988): Harrison Ford stars as a man whose wife disappears from their Paris hotel room after she accidentally picks up the wrong suitcase at the airport.

High Anxiety (1977): Hitchcock himself loved Mel Brooks’ spoof of his trademark style, jam-packed with wink-wink homages to Hitchcock’s best known films and featuring a theme song worth the price of admission all by itself.

The Spanish Prisoner (1997) David Mamet’s witty, fast-talking movie about corporate espionage owes a huge debt to Hitchcock’s unpredictable narrative twists and turns.

Homeschool Unit Study: The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

Books

Albert Marrin’s Civil War trilogy — Commander in Chief: Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, Unconditional Surrender: U.S. Grant and the Civil War, and Virginia’s General: Robert E. Lee and the Civil War (though this one is a little more apologist for Lee than I prefer)— makes a great read aloud spine for your Civil War studies if you are interested in the war part of the Civil War. Marrin does an excellent job illuminating the personalities and events of the Civil War while still presenting a straightforward, chronological history of the war.

Janis Herber’s The Civil War for Kids: A History with 21 Activities includes hands-on projects like making butternut dye (used by Confederate soldiers on their uniforms), baking hardtack (a food staple for soldiers in the fields), and decoding wigwag (a flag system used to pass messages long distances during the Civil War). This is written for younger students, but I find that high schoolers enjoy a few hands-on activities in their history studies, too.

How can neighbors fight on different sides of the same war? Harold Keith’s Rifles for Watie does a nice job illustrating the complexities of the war through the experiences of fictional Kansas teenager Jefferson Davis Bussey, who finds himself fighting for both the Union and Confederate armies over the course of the war. Keith also focuses his narrative on the war’s western front, which may not be as familiar to younger historians.

The Civil War was the first technology-assisted war, and new weapons, communication devices, and transportation systems played a significant role in the war’s outcome. In Secrets of a Civil War Submarine: Solving the Mysteries of the H. L. Hunley, Sally Walker explores the history of the Confederate submarine that became the first submarine to sink a ship in wartime — though it never resurfaced after the battle. Walker tackles both the science and history of the submarine’s Civil War days and the modern-day forensic work of discovering and investigating the sunken vessel.

Talking about slavery can be one of the hardest parts of studying the Civil War with your kids. Many Thousand Gone: African Americans from Slavery to Freedom by Virginia Hamilton manages to tackle to subject with a rare combination of sensitivity and thoroughness.

When Steve Sheinkin was writing history textbooks, he hated that the most interesting bits always seemed to get left out. He cheerfully remedies that problem in Two Miserable Presidents: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You about the Civil War, an engrossing, anecdote-rich history of the War Between the States that’s equal parts smart and surprising.

Irene Hunt’s Across Five Aprils focuses on life on the homefront. There are no heroic charges or dramatic battles for teenage Jethro Creighton, just the increasingly difficult task of keeping the family farm going while his brothers are away fighting in the Civil War.

In the Shadow of Liberty by Kenneth C. Davis isn’t just about the Civil War — but its collected biographies of Black Americans who were enslaved by former U.S. Presidents illuminate the hypocrisy lurking behind “the land of the free.” This book is an important reminder that talking about the Civil War without talking about how the United States justified, protected, and relied on slavery kind of misses the point.

Paul Fleischman’s Bull Run is a collection of sixteen monologues reflecting the personal experiences of people of different ages, races, genders, and regions during the First Battle of Bull Run.

Soldier’s Heart by Gary Paulsen is not an easy book to read, but this novel about 15-year-old Charley Goddard, who enlists with the First Minnesota Volunteers at the start of the Civil War and who returns home four years later, forever changed by his experiences, is powerful stuff.

Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts by Rebecca Hall is a fascinating graphic novel history of Black women’s leadership in enslaved people’s uprisings. I learned so much reading this book! Similarly, Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s biography She Came to Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman is a brilliant reminder that Black Americans were fighting against slavery before and during the Civil War.

The lasting impact of the Civil War is the central focus of Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. Though it’s more appropriate for older readers, Horowitz’s journey into the legacy of the Confederacy in the modern-day South raises the kinds of questions that can keep you talking for days.

Movies

Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990) is the undisputed must-see Civil War documentary. Though Burns caught some flack from historians for his“American Iliad,” his epic history of the Civil War is rich with details and emotionally charged. Balance it with thoughtful conversations about slavery and Reconstruction.

Glory (1989) tells the story of the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a platoon of African-American soldiers whose assault on Fort Wagner at the Battle of Fort Wagner helped the Union army win that battle. Though the story is exciting enough to be fiction, it’s firmly rooted in real historical details.

Gettysburg (1993) is based on Michael Shaara’s excellent novel The Killer Angels and was filmed on the battlefields of Gettysburg. The film focuses on the 1863 battle that prompted Lincoln’s famous address. (The follow-up film, Gods and Generals, is worth watching, too, if you want more.)

The tear-jerker ending of Shenandoah (1965) softens the film’s anti-war message, but the toll of war off the battlefield remains a major theme. Jimmy Stewart plays a Southern farmer who wants nothing to do with a war that doesn’t concern him — until his family, like so many families, is affected by the violence of the war.

Online Resources

The Valley of the Shadows project chronicles the history of two communities — Franklin County in Pennsylvania and Augusta County, Virginia — through the years leading up to, during, and following the Civil War. Thousands of primary sources tell the story of what life was like for people living through one of the United States’ most turbulent periods.

It would be hard to overemphasize the importance of the railroad in the progress and outcome of the Civil War, and the digital history project Railroads and the Making of Modern America walks you through the railroad’s role in military and political strategy.

The National Park Service’s Civil War hub has lots of information about the War Between the States, but one of the most practical resources for homeschoolers in search of a field trip is the comprehensive list of Civil War landmarks around the country.

One of the most interesting things about the Freedmen and Southern Society Project is its illumination of the role that slaves themselves played in the emancipation process.

Was the Civil War inevitable? See for yourself, as you face the same choices President Lincoln did in Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads, an interactive game developed by the National Constitution Center.

The 1862 battle at Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg) inspired Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. You can trace the pivotal battle online at Antietam on the Web, which includes handy maps and information about participants on both sides of the field.

Sherman’s march to the sea, cutting a swath of destruction through Georgia and effectively cutting off the Confederate Army, may be one of the best-known campaigns of the Civil War — and you can follow General Sherman’s route on the interactive maps at Sherman’s March and America: Mapping Memory.

The lines between North and South weren’t always as simple to draw as history books suggest, and New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War explores New York’s complex place in the war. The city supported a thriving abolitionist movement even as it relied on slavery-supported economic ties to the South.

Field Trip

Appomattox Courthouse National Historical Park has a full schedule of reenactments, lectures, guided battlefield walks, and more to commemorate Lee’s surrender here 150 years ago.

The Hero’s Journey: A Book and Movie List

The hero’s journey is so prevalent in film and books that it makes a great jumping off point for a comparative literature study, and these texts are a great place to begin.

Joseph Campbell’s take on the Hero’s Journey is maybe a little sexist (skip to the end for a different version), but it is reflected in centuries of great storytelling. The hero’s journey is so prevalent in film and books that it makes a great jumping off point for a comparative literature study, and these texts are a great place to begin.

You don’t have to be familiar with the hero’s journey to appreciate epics like the Odyssey and Beowulf, but the hero’s journey does provide a surprisingly useful framework for exploring classic Western literature. (Even Bluey uses it!) Sometimes, it can be just as interesting to look at the ways a text DOESN’T line up with the traditional hero’s journey — there’s a lot of conversation in the counterargument.

MOBY DICK

Ishmael signs on for a three-year journey on the whaling ship Pequod, entering Campbell’s belly of the whale as he cuts himself off from the known world to pursue a literal white whale through the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.

JANE EYRE

When she leaves her beloved Mr. Rochester and Thornfield Hall, Jane enters the English countryside equivalent of the Underworld: penniless, friendless, and fraught with trials and temptations.

THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN

Jim — with his combination of river knowledge and complex commitment to superstition — serves the role of Huck’s wise companion on their journey down the Mississippi River.

DUNE

Frank Herbert takes a subversive approach to the hero’s journey, following its patterns but raising questions about the nature and value of heroes. “The bottom line of the Dune trilogy is: beware of heroes. Much better to rely on your own judgment, and your own mistakes,” said Herbert.

THE MATRIX

Morpheus stands in for the father in Neo’s journey into the real world, and Neo can’t achieve full consciousness to fulfill his destiny until he understands his father’s teachings.

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ

A tornado sweeps Dorothy across the threshold and into the land of Oz, where she must follow a literal Road of Trials (paved in yellow brick) to complete her hero’s journey.

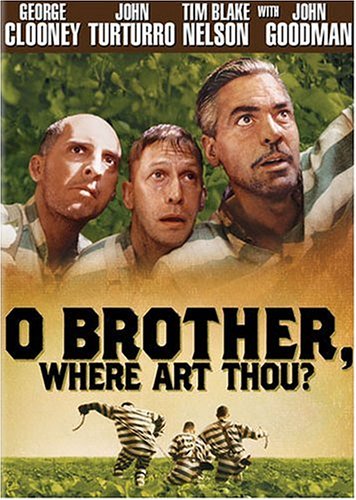

Like Odysseus, on whom he’s based, Ulysses Everett McGill can only end his journey when he’s reunited with his family and his home is restored.

LABYRINTH

This fantasy twists traditional gender roles as a teenage girl takes up the hero mantle and is tempted by a Goblin King — played by David Bowie, which makes it easy to sympathize with how hard he is for our heroine to resist.

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

Who knew a picture book could be so epic? But you can trace Max’s journey from the call to adventure to the freedom to live (and eat supper).

A group of kids follow the hero’s journey in this film, which ties its happy ending into the literal treasure the children bring back from their Underworld adventure.

STAR WARS

George Lucas sets the hero’s journey in space, but Luke Skywalker’s journey from farm boy to savior of the galaxy echoes the classic journeys of Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and other epic heroes.

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

Scout may be just a kid, but she heeds the call to adventure aided by the guidance of her wise mentor father.

And finally: For a feminist exploration of the hero’s journey, pick up From Girl to Goddess: The Heroine's Journey through Myth and Legend, which explores multicultural myths and folktales with female protagonists.

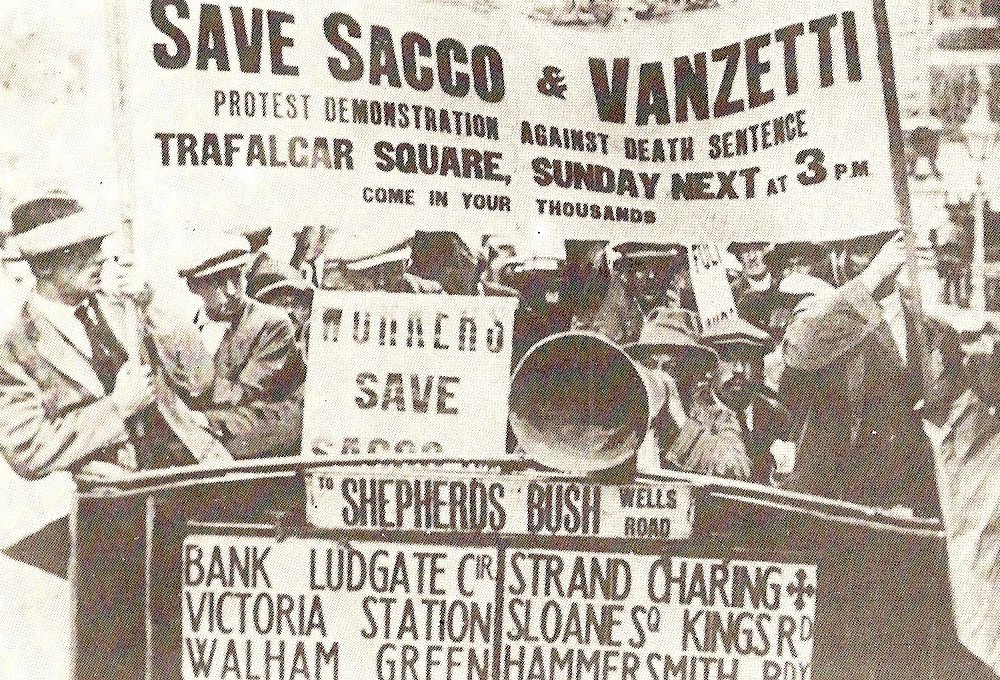

Homeschool Unit Study: The Sacco-Vanzetti Case

One of the most notorious trials of the 20th century United States makes a great starting point for big conversations about racism and the Red Scare.

How impartial is the U.S. justice system really? A deep dive into this notorious 20th century court case gives historical context for that big question.

The Sacco-Vanzetti case, which began in April 1920, remains one of the most controversial and debated cases in U.S. history. Did Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti commit the murder for which they were executed? The answer to that question remains less important than the other questions about immigrants, political opinions, and justice that it continues to raise. This is just one case, but digging into with your high schooler reveals a lot about the United States in the 1920s, anti-immigrant sentiment, and the Red Scare.

The Case:

On April 15, 1920, robbers killed a paymaster and a guard at a shoe factory in South Braintree, Massachusetts before escaping. Suspicion fell on two naturalized Italian immigrants: Nicola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a fish peddler. Sacco and Vanzetti were ideal villains — as atheists, draft avoiders, and anarchists, they represented a triple-threat to American ideas about the importance of religion, country, and property.

The problem was that they might not actually have been villains. Caught up in a maelstrom of prejudice and fear, their case moved rapidly to court and execution, in the end resembling a slow-moving lynch mob as much as an organized pursuit of justice. Neither man had a criminal record, and there was no evidence against them. Another known criminal actually confessed to the crime while the trial was happening. Despite numerous appeals and evidence of the innocence, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed August 23, 1927.

Listen to this: The Past Present: History For Public Radio’s episode on Sacco and Vanzetti includes historical audio of the defendants and other people involved in the case, Woody Guthrie ballads, Italian anarchist songs, and readings from the letters Sacco and Vanzetti wrote from prison. (Scroll to the bottom to download the full program.)

Talking point: Why were anarchists targets for suspicion in the 1920s United States?

Read this: How did people feel about the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti? The New York Times gave them the day’s main headline, and for the first time in modern history, the city of Boston shut down Boston Common in fear that activists would congregate there. The poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, one of many artists who tried to have the verdict overturned, wrote, “[the] men were castaways upon our shore, and we, an ignorant savage tribe, have put them to death because their speech and their manners were different from our own, and because to the untutored mind that which is strange is in its infancy ludicrous, but in its prime evil, dangerous, and to be done away with.’ And the Atlantic Monthly published a long essay by future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter highlighting some of the major problems with the case.

Talking point: How did anti-immigrant sentiment contribute to the sentence in this case? (You may want to look up the immigration quotas of 1924, which passed while Sacco and Vanzetti were in prison.)

Explore this: You can visit the virtual exhibit Sacco & Vanzetti: Justice on Trial from Boston’s John Adams Courthouse online and explore the history and after math of the trial, including court transcripts like this cross-examination of Sacco:

QUESTION: Did you love this country in the last week of May, 1917?

SACCO: That is pretty hard for me to say in one word, Mr. Katzmann

QUESTION: There are two words you can use, Mr. Sacco, yes or no. Which one is it?

SACCO: Yes.

Talking point: Would it have been possible for Sacco and Vanzetti to get a fair trial somewhere else?

Watch this: Tony Shaloub and John Turturro lend their voices to Peter Miller’s 2006 documentary Sacco and Vanzetti, which recreates the trial and incorporates modern forensic evidence.

30 Ideas (One for Every Day!) for Celebrating Poetry Month in Your Homeschool

It’s National Poetry Month, so let’s celebrate with a roundup of 30 ways to explore poetry in your secular homeschool.

Celebrate National Poetry Month this April with an inspiring activity for every day.

DAY 1: LAUGH IT UP

The National Poetry Foundation’s satiric send-up of what a world with plenty of everyday poetry might look like (Rachel Maddow hosts the MSNBC special “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays” and ESPN2’s best memorizer competition hits the big time) is hilarious.

DAY 2: LISTEN UP

Log on to the Poetry Everywhere channel, where poets like Galway Kinnell and Adrienne Rich read their favorite and original poems.

DAY 3: FIND YOUR OWN WORDS

Use classic poems or speeches as inspiration for your own poetic work with the Word Mover tool. For kids who have trouble getting those first words down on paper, this is a great place to start; for kids who love putting words on paper, it’s a great way to play with classic texts.

DAY 4: FIND A NEW FAVORITE POEM

A few we love: “Macavity the Mystery Cat” (T.S. Eliot), “April Rain Song” (Langston Hughes), “Sick” (Shel Silverstein), “About the Teeth of Sharks” (John Ciardi), “Rabbit” (Mary Ann Hoberman), “The Adventures of Isabel” (Ogden Nash), “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening” (Robert Frost), “What Is Pink?” (Christina Rossetti)

DAY 5: ORGANIZE AN EXHIBITION

Put together a homeschool Poetry Out Loud competition in your town. Whether you decide to choose a winner or not, this recitation exhibition brings poetry to vivid life.

DAY 6: BE INSPIRED

Listen to three teens from the Santa Fe Indian School practice their recitations for the National Youth Poetry Slam Festival in Washington D.C.

DAY 7: MAKE A BLACKOUT POEM

All you need is a newspaper and a Sharpie to make poetry. Scribble out words and sentences on a newspaper page, leaving uncovered carefully chosen words to make a poem. (Tip: Arts pages often have better words to choose from than a newspaper’s front page.)

DAY 8: HAVE A POETRY TEA

Make a Tuesday date around the table to share your favorite poems over a traditional afternoon tea.

DAY 9: SAY HI TO HAIKU

Read classic haiku and master the skills you need to write your own seventeen-syllable poems (in lines of five, seven, five) with this worskshop from the University of Colorado at Boulder's Center for Asian Studies.

DAY 10: GET NERDY WITH IT

Write a Fib, a six-line poem that uses the Fibonacci sequence to dictate the number of syllables in each line.

DAY 11: GO EPIC

What makes a poem epic? Dig into the details of the history and characteristics of this distinctive poetic form.

DAY 12: STAGE A RECITATION

Memorize a poem and perform it for an audience, just like the “Friday concerts” in one-room schoolhouses.

DAY 13: START A COMMONPLACE BOOK

Make your own perfect-for-you poetry collection by copying your favorite poems into a notebook.

DAY 14: PLAN A BIRTHDAY PARTY FOR A POET

There are lots to choose from in April: Maya Angelou was born on April 4, William Wordsworth on the 7th, Charles-Pierre Baudelaire on the 10th, Seamus Heaney on the 13th, Shakespeare on the 23rd, Robert Penn Warren on the 24th, and John Crowe Ransom on the 30th.

DAY 15: TANKA YOU

When is a syllable not a syllable? When it’s an on, a Japanese sound unit used to set the strict metric tone for the Japanese tanka.

DAY 16: Make Poetry move

Students of all ages can be inspired by creating choreography for their favorite poems: Think of it as an interpretive dance that moves with words instead of music.

DAY 17: MAKE A CONNECTION

The Academy of American Poets invites students to write their own poetry in response to poems written by Academy members — what a great reminder that poetry is an ongoing conversation, not just a monologue.

DAY 18: NOMINATE A POET FOR A STAMP

You can nominate any American poet who has been dead for at least ten years to be featured on a U.S. stamp. Send suggestions to: Citizens' Stamp Advisory Committee, c/o Stamp Development, U.S. Postal Service. 475 L’Enfant Plaza, SW, Room 5670, Washington, D.C. 20260-2437

DAY 19: LAUGH AT LIMERICKS

Make poetic sense of nonsense with an in-depth look at Edward Lear’s work and the limerick’s form and function.

DAY 20: READ ALOUD

Former poet laureate Billy Collins gives his best poetry reading tips — and suggestions for 180 poems to practice with — on the Poetry 180 website.

DAY 21: MAKE A POETRY COLLAGE

Choose a favorite poem — your own or another writer’s — and illustrate it with a collage. Magazine pictures, flower petals, scrapbook letters, colorful paper, and yarn all make handy collage supplies.

DAY 22: GET PUBLISHED

Mail an original poem to the Poetry Wall at the Cathedral Church of St John the Divine in New York City. All submissions, from poets known and unknown, are hung in the Cathedral’s ambulatory.

DAY 23: DISCOVER NEW POETRY

Former poet laureate Ted Kooser introduces hundreds of hand-picked poems as part of his American Life in Poetry project.

DAY 24: TELL A STORY IN POETRY

Learn about narrative poetry and poetic persona using Robert Frost’s poem “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening”and other works as your starting point.

DAY 25: MAKE EVERY DAY A POETRY DAY

Subscribe to the (free) Poem-a-Day newsletter from the Academy of American Poets, and you’ll get a poem in your inbox every morning. The selections are a nice mix of classic and modern.

DAY 26: GET DESCRIPTIVE WITH KARLA KUSKIN

Take an online workshop with poet Karla Kuskin to learn how to use strong, descriptive imagery and language in your poems.

DAY 27: CELEBRATE POEM IN YOUR POCKET DAY

Our second-favorite holiday (right after Read in the Bathtub Day), Poem in Your Pocket Day encourages you to carry a scribbled version of your favorite poem in your pocket to share with other poetry lovers throughout the day.

DAY 28: PLAY EXQUISITE CORPSE

In this surrealist take on MadLibs, players choose a syntax pattern (adjective, noun, verb, adverb, adjective, noun, perhaps) and take turns filling in the blanks to create a poem.

DAY 29: FALL IN LOVE

Read the poems of poets whose romantic relationships influenced their work, such as Elizabeth Barrettand Robert Browning, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, or Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell.

DAY 30: PLAY WITH SHEL SILVERSTEIN

Head straight for where the sidewalk ends on this fun-filled site. You’ll make your own rhymes, solve cryptograms, test your knowledge of Silverstein’s work, and more.

Homeschool Reading List: The Big Bang Theory

Dig into the science behind the Big Bang Theory with a book for homeschool scientists at every level.

Dig into the science behind the Big Bang Theory with a book for homeschool scientists at every level.

Cosmologist and theoretical physicist George Gamow and his fellow scientists first proposed the Big Bang Theory seventy years ago, and their ideas about how the universe began remain our best-guess understanding of the universe’s origins. It’s a fascinating theory to dive into with your homeschoolers, whether they’re young or preparing for college.

Resources for Young Scientists

These resources are appropriate for elementary and early middle school students.

The Everything Seed: A Story of Beginnings by Carole Martignacco

Framed as an origin myth, this joyful picture book explains the basics of the Big Bang theory and creates a creation story that’s based in actual science.

Bang! How We Came to Be by Michael Rubino

Focusing on the story of evolution from the singularity that sparked the universe we know to the single-cell organisms that would eventually become us, this picture book is an exuberant celebration of science.

Older Than the Stars by Karen Fox and Nancy Davis

“You are older than the dinosaurs. Older than the earth.” So begins this scientific origin story of the universe, which explains how the larger cosmos and human beings within it came into existence.

The Birth of the Earth by Jacqui Bailey and Matthew Lilly

Part of the Cartoon History of the Earth series, this comic book exploration of the universe’s origins is great for beginning readers. (The timeline is especially useful for making sense of cosmic time.)

Resources for Older Scientists

Use these resources when your students are ready for more sophisticated science.

NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe website walks you through the cosmology, theory, and concepts behind the Big Bang theory in an organized (and continuously updated) series of pages. It makes a terrific orientation and an informative jumping-off point for more in-depth studies.

The Book of the Cosmos: Imagining the Universe from Heraclitus to Hawking by Dennis Richard Danielson

Cosmology has fascinated scientists since the beginning of written history, and this collection of writings chronicles that fascination and its developing understanding of the universe through human history. (If you want to jump straight to the Big Bang, go directly to chapter 67.)

Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe by Simon Singh

Singh brilliantly humanizes the Big Bang, focusing on the (sometimes funny, often surprising) stories of the scientists who pieced together the universe’s cataclysmic beginnings from research, observation, testing, and the occasional sci-fi movie.

The Left Hand of Creation: The Origin and Evolution of the Expanding Universe by John D. Barrow

When you’re comfortable with the basics, dive deep into this dense, provocative exploration of particle physics that asks (and offers some possible answers for) big questions about the origin and development of the universe, the nature of time, and the connections between the origins of the universe and our own lives, right down to our genetic structure.

Homeschool Unit Study: Introduction to Shakespeare

Dive into one of literature’s great authors with a homeschool study of Shakespeare this spring.

Dive into one of literature’s great authors with a study of Shakespeare this spring.

“Shakespeare knows what the sphinx thinks, if anybody does,” wrote Thomas Quayle in 1900 — and though it’s been more than 400 years since William Shakespeare’s birth (in April 1564), the Bard of Avon remains as literarily essential and personally mysterious as he has been since his first show at the Globe Theatre. Dive into one of literature’s great authors with a study of Shakespeare this spring.

Start here:

We know surprisingly little about the historical Shakespeare’s life, but Shakespeare: His Work and his World is a cogent, kid-friendly introduction to his life.

Best Beginner’s Shakespeare

The play’s the thing — but if you’re not quite ready to tackle the plays proper, these texts make useful introductions.

Stories from Shakespeare by Geraldine McCaughrean outlines Shakespeare’s best-known works intelligently and articulately.

Lois Burdett’s Shakepeare Can be Fun series includes five popular plays, retelling their stories in rhyming couplets. The author, who runs a Shakespeare workshop series for kids, writes with staging in mind, so don’t be surprised if your living room becomes the stage for Romeo and Juliet.

Mr. William Shakespeare’s Plays by Marcia Williams uses actual dialogue, comic strips, and imagined comments from the Globe theater audience to help younger readers make sense of Shakespeare’s best known plays.

Shakespeare in Fiction

Living books bring the historical Shakespeare and his time to life and can be a natural lead-in to the author’s plays.

In King of Shadows by Susan Cooper, a modern-day American, in London to play Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, timeslips to the play’s original performance at the Globe Theatre. Shakespeare, who becomes a father figure to teenage Nat, is one of the main characters.

The Shakespeare Stealer by Gary L. Blackwood introduces Widge, an Elizabethan orphan with a knack for shorthand and acting who gets corralled into trying to steal a draft of Shakespeare’s new play Hamlet for an unscrupulous theater manager.

Add a little mystery to your Shakespeare studies with Simon Hawke’s Shakespeare and Smythe series, in which the Bard teams up with an intelligent ostler to solve mysteries that bear a suspicious resemblance to Shakespeare’s future plays.

Critical Readings

When you’re ready to dig deep into the Bard’s work, these dense but insightful texts will point you down delightful rabbit trails.

Originally published in 1934, Caroline Spurgeon’s Shakespeare’s Imagery and What It Tells Us, takes a focused look at Shakespeare’s imagery and what it implies, both about the writer and his relationship with his fellow Elizabethan and Jacobean writers, is utterly fascinating.

The Genius of Shakespeare considers the ways Shakespeare’s work has inspired others, being reinvented and re-envisioned by each new generation. Scholarly, and occasionally gossipy, it’s one of the most readable studies of the Bard.

For a lighter, lively study that focuses on known facts over speculation, Bill Bryson’s Shakespeare: the World as a Stage is thorough and engaging.

Charles Nicholl's The Lodger Shakespeare: His Life on Silver Street is an unexpected delight, focused on a single 1612 lawsuit in which Shakespeare gives testimony in a dispute involving a a daughter, a dowry, and a wig-maker.

Fun Activities

Think of these projects as hands-on ways to experience the pleasures of Shakespeare.

Play Mad Libs with a list of words coined by Shakespeare.

PBS’s Shakespeare Uncovered series follows well-known actors as they explore the history and significance of Shakespeare’s plays; e.g., Ethan Hawke investigates Macbeth, and David Tennant goes backstage with Hamlet.

The Shakespeare Unlimited podcast looks at Shakespeare’s influence — not just in literature and theater (though there’s plenty of that) but also in science and history.

Even if you can’t swing a field trip to the actual Globe Theatre this year, you can take a virtual backstage tour.

Masterpuppet Theatre includes 60 finger puppet cards of memorable Shakespearean figures and 12 backdrops.

Bonus:

If you have the time and inclination, you may enjoy these sci-fi Shakespeare adaptations.

Shakespeare’s Loves Labors Won accidentally summons a group of a group of Eldritch Abominations in Doctor Who’s “The Shakespeare Code.” (Oops.)

Shakespeare in Space: William Shakespeare’s Star Wars retells the Skywalker saga, Shakespeare style.

And here's a list of our favorite Shakespearean film adaptations from the home/school/life blog.

Update Your Homeschool First Aid Kit for Spring Adventures

A well-stocked first aid kit ensures that you’ll be ready when the urge for homeschool adventure strikes.

A well-stocked first aid kit ensures that you’ll be ready when adventure strikes.

Carry On

Stash your first aid essentials in a sturdy, water-resistant case, and you never have to worry about soggy bandages or crushed tweezers. Waterproof toiletry bags or small backpacks are good choices for day-tripping adventurers.

We Like: Holly Aiken Jet Pack, $169

(But if this isn’t something you want to splurge on, hit the toiletry aisle at Target —they have lots of cute bags.)

TIP: Get a card laminated that lists the num- bers for your pediatrician, local hospital, fire, and police departments, the Poison Control hotline (800-222-1222), and two emergency contacts who could be notified in case of emergency, and keep it in your first aid bag.

Heat Index

One-use disposable thermometers are handy when you don’t have a convenient place to sterilize between uses. ‘

NexTemp Single-Use Clinical Thermometers, $17 for 100

TIP: Kids who don’t like having their temperature taken may change their minds when you tell them these are the same thermometers NASA astronauts use on missions.

Cleaner Pastures

When you can’t wash your hands, sanitizer gel helps keep scrapes and injuries sterile.

Honest Hand Sanitizer Gel, $3

TIP: Make sure you choose a gel that has at least 60 percent alcohol and have kids use a quarter-size dollop and scrape their nails over their palms for best results.

Insult to Injury

Sure, you can use regular bandages, but wherefore wouldst thou?

Shakespearean insult bandages, $7

TIP: The Red Cross recommends making sure your first aid kit has at least 25 adhesive bandages (preferably in a variety of sizes) if you’re using it with a family of four.

Heal Appeal

UA hemostatic sponge can stop bleeding fast by sealing up the wound.

QuikClot Sport, Advanced Clotting Sponge 25G, $30

Happy Hydration

Use one tablet per liter of water if you need to fill your water bottle from a natural source.

Aquatabs Water Purification Tablets, $11

Whine Spritzer

Spray-on triple-antibiotic ointment won’t goop up your kit and is easy to apply one-handed. (Each tiny container holds about 140 applications.)

Neosporin Neo To Go! First Aid Antiseptic/Pain Relieving Spray, $7

Brace Yourself

Kids barely have to slow down to slip on insect-repellent bracelets, which last up to 100 hours when you keep them properly stored in your first-aid kit.

Buggy Bands Insect Repellent Bracelet, $30

TIP: Prefer a more traditional spray? Plant-based repel lemon eucalyptus works similarly to products that contain 25-percent DEET but without the ick factor.

Guide Book

Stash a pocket-size emergency first-aid guide in your kit so that — even without cell service — you can treat a sprain, handle a wasp sting, or (gulp!) deliver a baby in the wild.

Emergency First Aid Pamphlet, $8

Tie One On

Soak it in water to help an overheated kid cool down, tie it for a makeshift sling, or use it to secure a splint. You’ll never be sorry you stashed a bandana.

Cotton Bandana, $15

FIRST AID ESSENTIALS

Here’s what the Red Cross recommends keeping stashed in your first aid kit.

first-aid manual

sterile gauze pads of different sizes

adhesive tape

adhesive bandages in several sizes

elastic bandage

a splint

antiseptic wipes

soap

antibiotic ointment

antiseptic solution (like hydrogen peroxide)

hydrocortisone cream (1%) for rashes and bug bites

acetaminophen and ibuprofen

extra prescription medications (if needed)

tweezers

sharp scissors

safety pins

disposable instant cold packs

calamine lotion

alcohol wipes or ethyl alcohol

thermometer

tooth preservation kit

plastic non-latex gloves (at least 2 pairs)

flashlight and extra batteries

a blanket

mouthpiece for administering CPR (can be obtained from your local Red Cross)

your list of emergency phone numbers

Tips to Make Homeschooling Math Less Stressful

If math is a pressure point for your homeschool middle or high school student, you’re not alone! Math anxiety affects lots of kids, but with patience and persistence, you can help your student become math-confident.

When more than half of college students say that math stresses them out, what can you do to help your student shake math anxiety?

Make individual problems the focus.

Researchers in a 2011 study found that math-anxious kids performed almost as well (83 percent correct answers) as kids who didn’t worry about math (88 percent correct answers) when their concentration kicked in. By really focusing on one problem at a time, kids were able to work with less anxiety. Try practice worksheets with fewer problems on the page, or have students copy each new problem into a clean notebook page to isolate it.

Don’t assume it will just go away.

Math anxiety is like any other phobia and should be addressed accordingly, says Kaustubh Supekar, a researcher at Stanford University who has studied math anxiety in elementary and middle school students. Some students may need help learning to regulate their emotions more effectively in general before they can apply that skill to conquering math anxiety. If your student is anxious about math, pay attention to other places where they may feel anxious. It might not actually be about the math.

Find a good tutor.

According to Supekar, cognitive skill-building is one of the most effective ways to reduce math anxiety. Not only does it help kids solve math problems more successfully, it also lowers overall math anxiety levels over time, as students get more confident in their abilities. If you know how to get the right answer but don’t know how to explain what goes into getting the write answer, a tutor can help bridge that gap for your student.

Don’t share your own anxiety.

Plenty of homeschool parents stress about math, too, but math-anxious parents and teachers tend to pass their anxiety on to their kids, found researchers at the University of Chicago. If your child’s math has reached the point where you can’t comfortably solve problems with him, consider outsourcing your math classes — or sign up for a math class yourself to finally beat your own math anxiety.

DO YOU HAVE MATH ANXIETY?

Indicate your anxiety level in the following situations:

[1] not anxious at all, [2] a bit anxious, [3] somewhat anxious, [4] definitely anxious, or [5] extremely anxious. If you have more than five [4] and [5] answers, you may have math anxiety.

How anxious would you feel:

If you were given a set of arithmetic problems involving fractions?

Figuring out the tax on a purchase?

Standing in the supermarket line and trying to figure out if the total makes sense?

Splitting the check with friends at a restaurant?

Interpreting mathematical information in a news story?

Calculating the amount of money you save when buying something on sale?

Figuring out how much eight gallons of gas will cost at $2.66 a gallon?

Learning a new math skill?

Opening a math workbook?

Explaining how to solve a math problem?

Movies for Women’s History Month

Celebrate Women’s History Month this March with a homeschool movie marathon.

March is Women’s History Month, and every year, it feels more than ever like a time to think about how far women have come in the modern world — and how far we still have to go. These films will inspire and engage as you explore women’s history.

One Woman, One Vote

Susan Sarandon narrates PBS’s American Experience documentary on women’s rights, a well-rounded and informa- tion-rich introduction to women’s suffrage in the United States. Bonus: This documentary does a really nice job of exploring the role of black women in the suffrage movement.

Iron Jawed Angels

Hillary Swank and Frances O’Connor star in this sometimes weirdly directed but ultimately very compelling story about the U.S. battle for women’s rights. There are some invented historical incidents, but the overall story is rooted in real events.

Nine to Five

Maybe an indictment of women’s treatment in the 1980s workforce shouldn’t be this hilarious, but sometimes laughter really is the best social commentary.

Not for Ourselves Alone

Ken Burns takes on the women’s movement with this documentary focused on the lives of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two of U.S. history’s best known fighters for women’s rights.

The Magdalene Sisters

This film about the Irish institutions where“wayward women” were sent — and often abused — definitely deserves its R rating, so you may want to preview it. But since the last of these institutions didn’t close until the 1990s, it’s a movie worth watching with your older students.

The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter

The women who — more than capably — took on “men’s work” during World War II are the subject and stars of this poignant, powerful documentary.

A Midwife’s Tale

This fascinating documentary explores the life of an 18th century Maine midwife and the 20th century historian who discovered her diary and brought it to light.

14 Women

This sometimes overly earnest but still engaging 2007 documentary focuses on the — wait for it — fourteen female Senators in the 109th United States Congress.

Heaven Will Protect the Working Girl: Immigrant Women in the Turn-of-the-Century City

Before women won the right to vote, immigrant women crusaded for safer and more reasonable work conditions in booming factories and sweatshops. This short documentary illuminates their struggle — and victories.

The Burning Times

Some feminist scholars call the persecution of witches that occurred from the 1400s to the 1700s the “Women’s Holocaust” because of the huge number of women who were executed during this time. This documentary considers the history, causes, and effects of this problematic period in women’s history.

Great Nature Books for Your Spring Library List

Fill your library bag with books that will get your secular homeschoolers excited about spring — whether the weather's in the right mood or not.

Nature study isn’t just for the littles! Greener pages inspire greener pastures for middle and high school homeschoolers, too. These nature books will make you want to head outdoors, whether you’re looking for a new project to take on or just for a little motivation to make nature time part of your everyday routine.

THE STICK BOOK: LOADS OF THINGS YOU CAN MAKE OR DO WITH A STICK by Fiona Danks and Jo Schofield

Who knew a stick had so much potential? This book makes it clear why the humble stick was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame and gives kids lots of ideas for creative outdoor play. Tweens and teens can challenge each other to craft the best stick-based creations.

THE KIDS’ OUTDOOR ADVENTURE BOOK by Stacy Tornio and Ken Keffer

There are 448 ideas for playing outside in all seasons in this handy tome — that’s more than one idea for every day of the year. Kids will enjoy this book, but it’s also a good pick for parents who aren’t sure how to help their children ease into free play or make the transition from little kid outdoor to adventure to big kid outdoor fun.

OWL MOON by Jane Yolen

Your kids will want to take a nighttime owl walk after reading this poetic story about a child’s owling adventure with her father. A lot of us start to phase out these kinds of activities as kids get older, but this is actually the time when these activities can be the most magical.

AN EGG IS QUIET by Dianna Hutts Aston

An egg may not have a voice, but it’s still pretty interesting — a fact that this gorgeously illustrated picture book makes clear as it introduces readers to more than 60 different eggs, from fossilized dinosaur eggs to tubular dogfish eggs to giant ostrich eggs. If you’re studying biology, this is a fun springtime surprise to pull out for older students.

THE NATURE CONNECTION: AN OUTDOOR WORKBOOK FOR KIDS, FAMILIES AND CLASSROOM by Clare Walker Leslie

Clare Walker Leslie’s book about nature journaling changed the way I look at the natural world forever, and her follow-up guide, full of activities and ideas for experiencing and exploring nature with your family, is a must-have. I used this book when my kids were little and pulled it out on a whim when the oldest was finishing up middle school — it was like an entirely new book! Definitely worth revisiting even if you used it for elementary homeschool nature study.

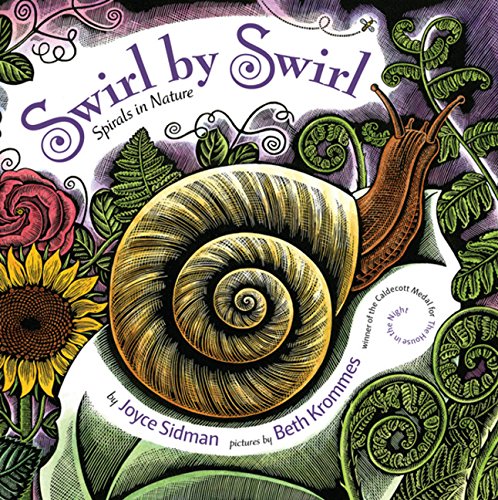

SWIRL BY SWIRL: SPIRALS IN NATURE by Joyce Sidman

A Newberry Honor poet and Caldecott medalist illustrator team up for this beautiful book about spirals in nature. This is a great book to inspire kids to look for shapes and patterns in the natural world and to get creative with how they think about nature study.

DIARY OF A CITIZEN SCIENTIST: CHASING TIGER BEETLES AND OTHER NEW WAYS OF ENGAGING THE WORLD by Sharman Apt Russell

Citizen science has big appeal for kids who want to be a part of something bigger, and this book, from a non-professional science fan who stalks tiger beetles, catalogs galaxies, and participates in other citizen science projects, makes an engaging read for older kids. (Bonus: You can find tons of citizen science projects to participate in if you’re feeling inspired.)

THE SENSE OF WONDER by Rachel Carson

Carson’s book, published in 1956, is hauntingly prescient, reflecting the importance of nature through a series of everyday outdoor experiences with her nephew along the Maine coast. This is a great book for reminding tweens and teens that their nature observations are part of bigger way of experiencing the world.

ALL THE WILD WONDERS: POEMS OF OUR EARTH edited by Wendy Cooling

Delicate watercolor paintings accompany nature poems by Christina Rossetti, Ogden Nash, John Agard, Thomas Hardy, and more. Kids who prefer writing to hiking may find that nature-inspired poetry is the perfect way to make outdoor time feel inspiring.

WALDEN by Henry David Thoreau

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Thoreau’s classic work about the importance of living a life connected to the natural world still resonates today, and teen readers will probably be both inspired by Thoreau’s ideas about a “simple” life and ready to critique some of the class and gender dynamics that are happening behind the scenes of that simple life.

THE CLOUDSPOTTER’S GUIDE: THE SCIENCE, HISTORY, AND CULTURE OF CLOUDS by Gavin Pretor-Pinney

Learn more about morning glory, cumulus, nimbostratus, and all those other clouds in this odd but awesome little book about the science, history, art, and pop culture significance of clouds. We spent hours making cloud charts and painting clouds in our high school nature study, and it was a welcome, meditative moment we looked forward to in our busy homeschool routine.

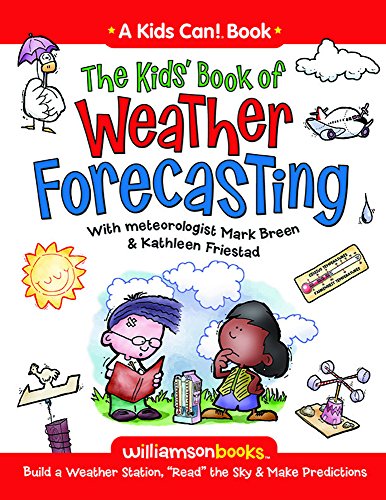

THE KID’S BOOK OF WEATHER FORECASTING: BUILD A WEATHER STATION, ‘READ THE SKY,’ AND MAKE PREDICTIONS! by Mark Breen and Kathleen Friestad

Who needs a weather unit study when you can build your own weather machine in the backyard? We tested this book out in elementary school, but my daughter was really too young to take ownership of the projects. Middle school proved to be perfect timing for us.

ROOTS, SHOOTS, BUCKETS & BOOTS: GARDENING TOGETHER WITH CHILDREN by Shannon Lovejoy

Lovejoy’s mix of practical information (you can start a garden with your kids using the information in this book) and inspiration (including a moon garden of night-blooming flowers) makes this an ideal volume for would-be gardeners of all ages.

TAKE A BACKYARD BIRD WALK by Jane Kirkland

Part of the Take a Walk series, this practical and engaging book helps kids develop the skills they need to notice and identify birds in their own neighborhoods. If you are just getting started with birdwatching, it’s not too late! And books like this make it much easier to let your tweens and teens lead the way.

A SEED IS SLEEPY by Dianna Hutts Aston

Sylvia Long’s accurate, detailed illustrations are a big part of what makes this book such a great addition to your nature library. Kids will learn about all kinds of seeds, from the ones light enough to float on the breeze to ones that can weigh up to 60 pounds. I think this would be a great book to include as part of a middle grades botany unit.

AND THEN IT’S SPRING by Julie Fogliano

Waiting and watching for signs of spring can sometimes feel like an endless process, a fact that Fogliano beautifully captures in this simple story. We read this book out loud every year when we’re on the lookout for those first indicators that winter is on the way out.

WHAT THE ROBIN KNOWS: HOW BIRDS REVEAL THE SECRETS OF THE NATURAL WORLD by Jon Young

A naturalist explores the language of birdsong in this book that manages to be both thoughtful and practical advice for birders. This is the kind of book that appeals to kids who explore their world like nature detectives, putting together clues and making deductions about how the world works.

SPRING: AN ANTHOLOGY FOR THE CHANGING SEASONS edited by Melissa Harrison

This tribute to British springtime includes spring-themed writings by Chaucer, Orwell, Hopkins, Larkin, and more. It’s a great gateway to comparative literature, exploring tone and mood, or digging into creating setting in literature — and it’s fun to read, too.

Alternatives to To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird is worth reading — but don’t make it the only book about racial justice on your list, or you’re missing the point.

Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird is worth reading — but don’t make it the only book about racial justice on your list, or you’re missing the point.

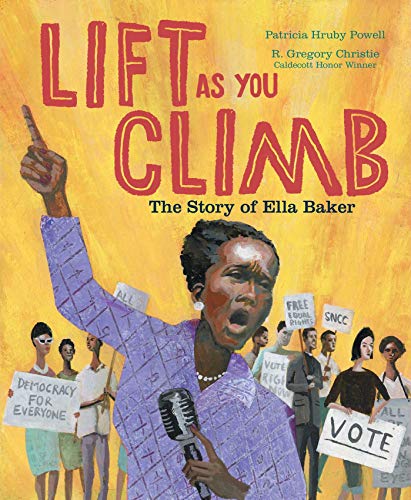

It’s not that Harper Lee’s coming-of-age classic isn’t a good book — it is. The problem comes when we try to make it the great American novel about racial justice — which it’s not. How could it be when it’s focused on racism as an incident in the coming-of-age story of a white woman and when its hero is a white man who never actually comes out and condemns racism? So read To Kill a Mockingbird — please read all the banned books! — but also read these books that shift perspective from a young white girl to actual experiences of people of color.

The Hate U Give BY ANGIE THOMAS

If Scout were a young Black woman and Tom Robinson was her friend, you’d get close to the vibe of this YA novel. Starr Carter lives in a poor Black neighborhood and attends a ritzy white private school, putting her smack in the middle of two worlds. Those worlds collide when her best friend is killed in a police shooting during a routine traffic stop — while Starr is sitting in the passenger seat. Like Mockingbird, The Hate U Give looks at the ways racism affects institutions we trust — like the courts or the police.

All American Boys BY JASON REYNOLDS AND BRENDAN KIELY

Quinn didn’t see what happened in the store, but he did see the aftermath: His friend’s police offer brother relentlessly beating Rashad. Told in Quinn and Rashad’s alternating perspectives as they navigate the aftermath of Rashad’s beating, this is a hard book to read in light of everything that’s happening in the world right now. That’s exactly why you should read it.

Dear Martin BY NIC STONE

Justyce is used to living in a world where the fact that he’s a young Black man is enough to make the people around him fear and suspect him — but that doesn’t mean he likes it. He finds solace writing letters to his hero Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who made great strides for Black civil rights — but who also ended up dead because of racism. (The sequel, Dear Justyce — about two friends who grow up together in Atlanta before their paths diverge — one to Yale University, one to the Fulton Regional Youth Detention Center — is also a contender.)

Internment BY SAMIRA AHMED

Mockingbird was set in the past, but Internment imagines the future: In a not-too-distant United States, Muslim-Americans are forcibly relocated to internment camps. Teenage Layla is one of them, and she’s more than ready to join the brewing rebellion. Though Internment has some literary flaws (including an unfocused second act and spotty character development), its premise is enough to make it worth reading. When is it OK to decide someone’s existence makes her a threat to society?

The Round House BY LOUISE ERDRICH

Young Joe is the Scout figure in this story: When his mother is raped and beaten, Joe wants to bring her attacker to justice, but the law around the Ojibwe reservation is so twisted and complicated that justice is hard to find, even for his father, who works as a judge. As his mother retreats more and more into herself, Joe turns to Ojibwe myths and spirits (which the book treats — appropriately — with the same world-shaping significance as Greek myths and spirits) to solve the mystery. This is a stark and lyrical reminder that justice looks different depending on the color of your skin and where you live.

Monster BY WALTER DEAN MYERS

Steve is on trial for his role in the shooting of a convenience store clerk — Steve was supposed to stand lookout while another kid robbed the store, but the clerk ended up dead. Steve didn’t kill him, though, so he doesn’t understand why his whole life has turned upside down. Of course, we see through Steve’s story that it’s more complicated than he wants to believe. The open ending means that we have to make up our own minds about how guilty Steve is — as well as what guilt the judicial system, racism, peer pressure, and profiling play in Steve’s trial.

The House You Pass on the Way BY JACQUELINE WOODSON

If you want a book entangled with rural Southern history but told from a Black perspective, Woodson’s dreamy, lyrical novel is a solid bet. Staggerlee’s grandparents are famous for dying in a civil rights era bombing. Her parents are infamous in their small town for their interracial marriage. Staggerlee knows she doesn’t want to become famous as “the gay girl” in town, but she can’t keep denying who she really is.

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption BY BRYAN STEVENSON

This non-fiction book illuminates the inherent racism of the U.S. criminal justice system through the story of one man's experiences. Stevenson demonstrates how the death penalty traces its roots back to Jim Crow "justice," pushing readers to question what they think they know about American justice and the American dream. The author is the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. (I’d probably read the original with high schoolers, but there is a young adult version if you’re reading with younger students.)

Beloved BY TONI MORRISON

This is the hardest book on the list — both in terms of complexity and subject matter — and not every kid will be ready to tackle this in high school. It’s worth reading if you have a student who can handle it, though. This is a horror novel — a gorgeous, dreamy, lyrical horror novel — about a woman who has escaped from slavery but remains haunted by its — literal — ghosts. This book recognizes the personal and na- tional trauma of slavery and its legacy in its dense, difficult story of the costs of surviving. Tom Robinson could be Sethe’s grandson; her history is his history.

How to Throw the Ultimate Homeschool Pi Day Party

Is Pi Day on March 14 (3.14) the ultimate homeschool celebration? At least it’s a fun reason to celebrate the magic of math, any way you slice it.

March 14 is Pi Day — and celebrating this mathematical constant makes a fun family party, any way you slice it.

Pi Day was one of the very first homeschool holidays we celebrated together — and like creating our first successful batch of oobleck, celebrating Pi Day was one of the things that made me feel like a “real” homeschooler. As the kids got older, our celebrations got wilder and more creative, and now I can’t imagine not throwing a little homeschool shindig to celebrate March 14 (3.14, the rounded-off version of pi). Here are some of our favorite Pi Day fun ideas:

DO THIS

Turn your wall clock into a pi clock by translating the hours into radians. (You can use the pi clock by SB Crafts as a model if you want to get fancy with your equations.)

Put your pi skills to the test with Buffon’s Needle, a geometrical probability problem that dates back to 1777. It involves dropping a needle onto a sheet of lined paper and determining the probability of the needle crossing one of the lines on the page — an answer that’s directly related to pi. The Mathematics, Science, and Technology Education (MSTE) division of the College of Education at the University of Illinois has a cool simulation that walks you through the problem.

Take the Pi Day Challenge. Matthew Plummer, a former math teacher at Boston’s Hanover High School, likes celebrating Pi Day so much that he created a delightful series of online pi puzzles — some of which call for mathematical solutions, some for research, and some for critical thinking.

Write a Pilish — a poem based on the successive digits of pi. The number of the letters in each word of your poem should equal the corresponding digit of pi: so, the first word would have three letters, the second one, the third four, and so on.

READ THIS

In Sir Cumference and the Dragon of Pi by Cindy Neuschwander, the bold knight’s son Radius must find the cure to the potion that turned his father into a fire-breathing dragon.

WEAR THIS

The Einstein Look-a-Like competition is a beloved part of Princeton University’s annual Pi Day celebration, so join the festivities by getting dressed in your Einstein-ian best.

EAT THIS

Pie, of course!

Homeschool Unit Study: The History of Spies

The end of winter is the perfect time for a secular homeschool unit study that takes a chronological deep dive into some of history's most celebrated spies.

This winter is the perfect time to take a chronological deep dive into some of history's most celebrated spies.

Francis Walsingham (ca. 1532–1590)

Queen Elizabeth’s adviser was the first great English spymaster, and the culmination of his secret intelligence work was the frame-up, capture, and execution of Mary Queen of Scots in 1586. Most of Walsingham’s efforts were directed against the Catholics, whom Walsingham, a staunch Protestant who vividly remembered the Protestant purges initiated by Elizabeth’s sister and predecessor, feared and mistrusted. Walsingham organized a spy network that would impress modern day intelligence agents, complete with forgers who could copy any seal, an army of letter interceptors, complex ciphers to protect his own mail, and spies everywhere.

Read This:

The Queen’s Agent: Francis Walsingham at the Court of Elizabeth I by John Cooper

Benjamin Tallmadge (1778)

The so-called Culper Ring, led by Benjamin Tallmadge, tracked Tory troop activities in British-occupied New York City by actually joining Tory militias, feeding crucial information to the colonial army. They’re also credited with helping to bring down Benedict Arnold.

Read This:

Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring by Alexander Rose

Mary Bowser (1860s)

Mary Bowser joined the Richmond Underground, a movement that worked to get enslaved people, Union prisoners, and Confederate deserters out of occupied Richmond, Virginia. When she managed to get work at the Confederate White House, Bowser was able to pass important confidential information on to the Union.

Read This:

Spy on History: Mary Bowser and the Civil War Spy Ring by Enigma Alberti and Tony Cliff

Belle Boyd (1860s)

The Confederates had their spies, too, and 17-year-old Maria Isabella Boyd was one of them. Under guard for shooting a drunken Union solider who had insulted her and her mother, Belle charmed secret information out of her guard and passed it on to the Confederate troops.

Read This:

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War by Karen Abbott

Sidney Reilly (1890s-1925)

The “Ace of Spies” was the model for Ian Fleming’s James Bond. The handsome, womanizing Russian-born British agent spied on 1890s Russian emigrants in London, in Manchuria on the cusp of the Russo-Japanese War, and participated in an attempted 1918 coup d’etat against Lenin’s Soviet government. Reilly disappeared in the Stalinist Soviet Russia of the 1920s.

Watch This:

Margarethe Zelle (1914-1917)

Better known as Mata Hari, Zelle became one of the most famous spies in history even though chances are pretty good that she never actually did any spying: She was recruited by the French and by the Germans, both of whom saw potential in her globe-trotting work as an exotic dancer, but she doesn’t appear to have given any intelligence to anyone. Still, when the Germans outed her as a double agent, the French had her arrested and executed tout suite, despite a lack of actual evidence.

Read This:

Femme Fatale: A New Biography of Mata Hari by Pat Shipman

Virginia Hall (1930s-1940s)

“The limping lady” — so named because she’d shot herself in the foot and 1932 and replaced her amputated lower leg with a prosthetic limb — volunteered her services as a spy in occupied France, coordinating the activities of the Resistance under cover as a correspondent for the New York Post. Hall’s prosthetic foot, which she named Cuthbert, provided a convenient hiding place when smuggling top secret documents.

Read This:

The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy by Judith L. Pearson

Klaus Fuchs (1940S-1950S)

Fuchs was a nuclear physicist who left Germany in 1933 to come to England, where he worked on “Tube Alloys,” the British atomic bomb project, before joining the Manhattan Project in the United States. Fuchs hated the Nazis, but he had complicated feelings about the post World War II world — which led him to feed information to contacts in the Soviet Union. Fuchs was arrested for espionage in the 1950s and imprisoned.

Read This:

The Spy Who Changed the World: Klaus Fuchs, Physicist and Soviet Double Agent by Mark Rossiter

Melita Norwood (1962-1999)

Norwood worked as the assistant to the director at a British atomic research center for 37 years before her employers realized that she’d been passing secret information from her job on to the Soviets the whole time she’d worked there. By that time, Norwood was an 87-year-old grandmother, whose 1999 arrest made headlines and shocked everyone who knew her — including her family.

Watch This:

Expand your study further with these spy books for kids:

Spy Science: 40 Secret-Sleuthing, Code-Cracking, Spy-Catching Activities for Kids by Jim Wiese

How to be an International Spy: Your Training Manual, Should You Choose to Accept It by Lonely Planet Kids

DK Eyewitness Books: Spy: Discover the World of Espionage from the Early Spymasters to the Electronic Surveillance of Today by Richard Platt

World War II Spies (You Choose: World War II) by Michael Burgan

Homeschool Unit Study: The History of Cuneiform

Ancient Mesopotamia’s writing system offers a peek into geography, history, culture, and class in the ancient world. Learn more with a secular homeschool unit study for middle and high school students.

Ancient Mesopotamia’s writing system offers a peek into geography, history, culture, and class in the ancient world. Learn more with a secular homeschool unit study.

Some time between 522 and 486 B.C.E., a patient scribe carved the story of the rise of Darius the Great into a cliff in western Iran, not once but three times in three different cuneiform script languages. The finished inscription is 49 feet high and 82 feet wide, a virtually indelible record of the triumph of the most famous man in the world at the time — but it would be more than 2,000 years before any English-speaking historian could read it.

Cuneiform, along with Egyptian hieroglyphics, is one of the two most ancient written languages in human history. The birth of writing 5,500 years ago in ancient Sumeria was probably born of economic need instead of creative energy: The earliest written records, tokens made of stone or clay, record business transactions. Later, these tokens became pictographs, symbols inscribed on clay tablets that represented numbers or objects. Gradually, these symbols became more complex and sophisticated, and writing became about telling stories as much as about conducting business. By the time cuneiform faded from use — around the first century C.E. — people used it write letters, do schoolwork, write religious texts, and more.

Unlike an alphabet, cuneiform uses between 600 and 1,000 characters to write words or syllables — which may help explain why it was so difficult for Western readers to discover. To read it, you have to learn the language being recorded and then all the signs, which tend to have multiple possible meanings. Like other languages, cuneiform seems to be easier for children to pick up than for adults — many of the surviving cuneiform documents we have today are actually spelling and handwriting exercises probably done by Sumerian students.

Part 1: How Cuneiform Works

Do this:

Try this:

Pretend the alphabet doesn’t exist, and you have to invent a form of writing based around simple pictures. Brainstorm a basic system, and see if you can use it to write:

your name

a verb (like dance or read)

adjectives (like delicious or fun)

Talk about this:

What does picture writing do well? What are some advantages it might have? What limitations does picture writing have?

What is the purpose of writing? Think about commercial reasons (like buying and selling), political reasons (writing laws or training an army), and social reasons (telling stories or organizing religions).

Part 2: The Story of Writing

Do this:

Work through the interactive online activity The Story of Writing, which explores the development of the cuneiform character for barley over time.

Talk about this:

How does the development of the symbol for barley show how cuneiform evolved over time?

Think about this:

Why did the ancient Mesopotamians simplify their pictographs over time? How might this make writing faster or easier? What might be the implications of changing from direct representation (pictures) to abstract representation? (Think about who has access to education.)

Part 3: Writing as Artifact

Talk about:

Cuneiform gives us an idea of what life was like in ancient Mesopotamia and about what kind of lives the people from that place and time lived. So what does it tell us about these people that they started writing in order to record agricultural transactions? Why would these records be important? Who would benefit from recording these commercial transactions? (Think beyond the buyers and sellers — how might these records affect things like taxes and services?)

What else might be important to keep records of? (Births, marriages, and deaths? Property ownership? Work contracts? Religious rules and rituals?) How could writing be used to legitimize and extend political power? (Think of the carvings we talked about at the beginning of this unit — what is their purpose? How well did they succeed at accomplishing that purpose?)

Do this:

Explore some of the artifacts in the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute Tablet Collection. What do these artifacts tell you about life in ancient Mesopotamia?

Take a Virtual Field Trip to the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art has an eclectic collection that’s fun to explore with your homeschoolers. The museum is worth a visit, but you can also take a virtual tour of some of the collection’s highlights.

It’s the National Gallery’s birthday — and a virtual visit can start some awesome conversations about art in your secular homeschool.

March is the birthday of the National Gallery of Art, which was established March 17, 1941. Its mission was to make a broad swathe of art — from medieval altarpieces to abstract expressionism — accessible to all U.S. citizens, which is why it’s never charged an admission fee. The museum, which opened during World War Two, when cultural institutions in Europe were shutting down, represented both hope for the future and the importance of arts and culture, said then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who thought that art should be for the people, not just the elite who could afford to purchase it — which is why it’s appropriate that you can check out some of the highlights of its collection from the comfort of your own home.

Ginevra de Benci by Leonardo da Vinci

Da Vinci’s painting of the Italian woman poet is his only work permanently on display in the western hemisphere, and Ginevra’s expression is as inscrutable as the Mona Lisa’s.

Little Dancer by Degas

The only sculpture Degas ever put up for exhibition was almost universally scorned during its 1881 showing, but the ballerina statue has become one of the most famous in the world — and the original (complete with human hair in her braid) is at the National Gallery.

The East Wing by Alexander Calder

The East Wing of the National Gallery has the largest collection of the sculptor’s work, but the big draw — literally — is the unnamed sculpture in the entry. Calder didn’t believe in “naming the baby” until it was born, and since he died before this last — and largest — work was installed, it never received a name.

Hahn/Cock by Katharina Fritsch

The star of the rooftop, this giant electric blue rooster turns conventional art on its head: “I, a woman, am depicting something male. Historically it has always been the other way around,” says Fristch.

Into Bondage by Aaron Douglas

An unflinching depiction of the Atlantic slave trade and its impact on African-American life, Douglas’s painting is one of the masterworks of the Harlem Renaissance.

Great Readaloud Biographies for Women’s History Month

Looking for a great biography for Women’s History Month for your secular homeschool? We’ve got some suggestions for every grade level.

For Women’s History Month, take a homeschool road trip to some woman-powered regions of history that don’t always show up in traditional textbooks.

A note about reading levels: People ask me about reading levels a lot, and the truth is that I don’t think about reading levels a lot. I have had my most advanced high school students write dense academic papers about children’s and middle grades books, and I read Finnegan’s Wake to my daughter when she was in the NICU. In other words, I think if the book and the reader match, the reading level doesn’t really matter that much. Which is a long-winded way of saying that I would absolutely read all of these books with my tween and teen homeschooler and feel like we were doing solid academic work together.

Margaret Knight

With her father’s toolbox and her sketchbook of inventions, Mattie Knight could — and did — make almost anything, including flat-bottomed paper bags (which we still use today), a metal guard that protected textile factory workers from flying shuttles, and a numbering machine. In fact, she held 87 U.S. patents, earning her the nickname the “Lady Edison.”

Read more about her in:

Marvelous Mattie: How Margaret E. Knight Became an Inventor by Emily Arnold McCully

Bessie Coleman

Growing up in rural Texas, Coleman yearned to get out of the cotton fields and into school, so she made learning part of her life, checking the foreman’s numbers every day to practice her math. In her 20s, she moved to Chicago, where she learned French in order to study flying in France, where she became the first African-American pilot.

Read more about her in:

Fly High!: The Story of Bessie Coleman by Louise Borden

Elizabeth Blackwell

There weren’t any women doctors when Elizabeth Blackwell was growing up in the 1830s — so it’s not very surprising that the plucky girl met plenty of resistance (including 28 medical school rejections — ouch!) when she decided she wanted to be a doctor. Blackwell’s determination and hard work carried the day, however, and Dr. Blackwell became the first female doctor in the United States.

Read more about her in:

Who Says Women Can’t Be Doctors?: The Story of Elizabeth Blackwell by Tanya Lee Stone