Unit Study: Queen Victoria

You could spend years digging into the life of the British ruler who gave the Victorian age its name and still make new discoveries, but consider these resources a delightful starting point for a high school history homeschool unit study.

Celebrate Victoria Day on May 22 by learning more about the British queen it’s named for.

When Alexandrina Victoria took the throne of England in 1837, she was a teenager inheriting a seriously tainted monarchy. By the time of her death in 1901, the Queen had become a global symbol of the British Empire, the time period had become eponymous with her name, and she would successfully redefine royalty for the modern world. Some of this was luck, some of this was the people who surrounded her, and some of it was the sheer stubborn determination of Victoria herself. You could spend years digging into Victoria’s life and still make new discoveries about the 19th century queen, but consider these resources a delightful starting point.

READ

Who Was Queen Victoria? BY JIM GIGLIOTTI

This is a predictably solid entry in the reliable Who Was elementary biography series, covering Victoria’s life from unhappy childhood to triumphant Jubilees. (Elementary)

My Name Is Victoria BY LUCY WORSLEY

Worsley imagines Victoria’s life through the eyes of her forced companion, John Conroy’s daughter — also named Victoria — who is brought to Kensington Palace to spy on the Queen-to-be but finds herself sympathetic instead. (Elementary)

Victoria: May Blossom of Britannia, England, 1829 BY ANNA KIRWAN

This historical fiction novel is part of the Royal Diaries series, so its focus is on Victoria’s unhappy princess period, when she dreams of being Queen as a way to escape her miserable life at Kensington Palace. (Middle grades)

Victoria Victorious BY JEAN PLAIDY

Jean Plaidy is less sparkly than usual in this historical novel, and like so many writers, she dwells on the romance of the early half of Victoria’s reign, when she is a young queen in love with her husband, but this first-person story is a thoughtfully researched introduction to Queen Victoria’s life. (Middle grades)

Queen Victoria BY LYTTON STRACHEY

For the post-World War I view of Queen Victoria, turn to Lytton Strachey’s very un-Victorian biography, a classic, snarky history as full of royal gossip as historical details. (High school)

Victoria BY DAISY GOODWIN

This YA-friendly historical fiction biography focuses on Queen Victoria’s first two years as Queen of the British Empire, bringing to life the larger-than-life personalties who defined the early years of her reign, including the very charismatic prime minister Lord Melbourne, Victoria’s cousin (and future husband) Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Victoria herself. (High school)

Victoria: The Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire BY JULIA BAIRD

If you’d like a frothy biography that reads like a well-researched version of “Keeping Up with the Hanovers,” pick this up: Baird writes a little like a romance novelist and holds firm to her theory that Victoria secretly married her servant John Brown, but it’s a fun read. (High school)

We Two: Victoria and Albert: Rulers, Partners, Rivals BY GILLIAN GILL

Even though Victoria reigned for half her life without Albert, his influence on her was so great that he permanently shaped her ideas (for better and worse) about what a monarch, a parent, and a woman should be. This dual biography illuminates the most important relationship of Victoria’s life and the constant tension between power and family love that it inspired. (High school)

Victoria’s Daughters BY JERROLD M. PACKARD

It was not easy to be the offspring of the ruler of the British Empire and her perfectionist partner, and this group biography explores the lives of the five women who called Queen Victoria mother. It’s a sad and fascinating history of female life on top tier of British society, with a special interest in the life of rebellious Princess Louise. (High school)

Uncrowned King: The Life of Prince Albert BY STANLEY WEINTRAUB

I’m always telling my students that had Albert lived as long as his wife, we would probably be calling the 19th century the Albertine Era. Weintraub does a great job painting a vivid picture of the reform-minded, ethically intense polymath who proved the perfect romantic and political partner for the woman he was steered to marry since childhood. (High school)

The Letters of Queen Victoria BY QUEEN VICTORIA

One of the best ways to get to know someone is through her own words, and Victoria is no exception. The Letters of Queen Victoria put the Queen’s best foot forward, clearly demonstrating how the chief figure of the Victorian era wanted to be seen by the people in her world. (And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that her children re-edited these letters, too.) (High school)

WATCH

Victoria

Jenna Coleman’s Victoria is neither prim nor proper, but she’s certainly interesting in this fairly faithful BBC adaptation created by Daisy Goodwin. OK, it veers a little toward the romantic with heartthrobs cast as middle-aged Melbourne, aristocratic Albert, et al, but who are we to complain about a little eye candy in period costume?

The Young Victoria

Emily Blunt is the lonely little girl crowned Queen of England in this dreamy biopic focused on the years 1836 to1840. Paul Bettany is a particularly disreputable Lord Melbourne, Mark Strong is a particularly vile John Conroy, and Miranda Richardson is a conflicted Duchess of Kent, but Blunt steals the show with her Victoria torn between the desire for freedom and independence and longing for a real family.

Victoria the Great

This 1937 film focuses on the early years of Victoria’s reign. The film, commissioned by Edward VII in honor of his great-grandmother, includes sets and costumes that are accurate reproductions of actual items in the British museum.

Mrs. Brown

Judi Dench is glorious as a middle-aged Victoria who cannot seem to get her Queenly groove back after the death of Prince Albert. Only Albert’s Highland servant, John Brown, cheers her up, but friendship between a Queen and a rowdy Scotsman seems pretty scandalous.

Victoria and Abdul

Judi Dench reprises her role as Victoria in another historical account of the Queen’s fondness for her servants: This time, it’s focused on Victoria’s late-in-life friendship with her Indian servant Abdul Karim.

Ohm Krüger

For a totally different perspective, screen this World War II German propaganda flick about the Boer War, which paints Queen Victoria as a ruthless alcoholic who tricks the Germans into signing an unfair treaty.

PBS Empires: Queen Victoria

This series focuses on the politics and geography of the Victorian empire, which ruled one-fifth of the world’s people during Victoria’s 64 years on the throne.

Homeschool Unit Study: The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

Books

Albert Marrin’s Civil War trilogy — Commander in Chief: Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, Unconditional Surrender: U.S. Grant and the Civil War, and Virginia’s General: Robert E. Lee and the Civil War (though this one is a little more apologist for Lee than I prefer)— makes a great read aloud spine for your Civil War studies if you are interested in the war part of the Civil War. Marrin does an excellent job illuminating the personalities and events of the Civil War while still presenting a straightforward, chronological history of the war.

Janis Herber’s The Civil War for Kids: A History with 21 Activities includes hands-on projects like making butternut dye (used by Confederate soldiers on their uniforms), baking hardtack (a food staple for soldiers in the fields), and decoding wigwag (a flag system used to pass messages long distances during the Civil War). This is written for younger students, but I find that high schoolers enjoy a few hands-on activities in their history studies, too.

How can neighbors fight on different sides of the same war? Harold Keith’s Rifles for Watie does a nice job illustrating the complexities of the war through the experiences of fictional Kansas teenager Jefferson Davis Bussey, who finds himself fighting for both the Union and Confederate armies over the course of the war. Keith also focuses his narrative on the war’s western front, which may not be as familiar to younger historians.

The Civil War was the first technology-assisted war, and new weapons, communication devices, and transportation systems played a significant role in the war’s outcome. In Secrets of a Civil War Submarine: Solving the Mysteries of the H. L. Hunley, Sally Walker explores the history of the Confederate submarine that became the first submarine to sink a ship in wartime — though it never resurfaced after the battle. Walker tackles both the science and history of the submarine’s Civil War days and the modern-day forensic work of discovering and investigating the sunken vessel.

Talking about slavery can be one of the hardest parts of studying the Civil War with your kids. Many Thousand Gone: African Americans from Slavery to Freedom by Virginia Hamilton manages to tackle to subject with a rare combination of sensitivity and thoroughness.

When Steve Sheinkin was writing history textbooks, he hated that the most interesting bits always seemed to get left out. He cheerfully remedies that problem in Two Miserable Presidents: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You about the Civil War, an engrossing, anecdote-rich history of the War Between the States that’s equal parts smart and surprising.

Irene Hunt’s Across Five Aprils focuses on life on the homefront. There are no heroic charges or dramatic battles for teenage Jethro Creighton, just the increasingly difficult task of keeping the family farm going while his brothers are away fighting in the Civil War.

In the Shadow of Liberty by Kenneth C. Davis isn’t just about the Civil War — but its collected biographies of Black Americans who were enslaved by former U.S. Presidents illuminate the hypocrisy lurking behind “the land of the free.” This book is an important reminder that talking about the Civil War without talking about how the United States justified, protected, and relied on slavery kind of misses the point.

Paul Fleischman’s Bull Run is a collection of sixteen monologues reflecting the personal experiences of people of different ages, races, genders, and regions during the First Battle of Bull Run.

Soldier’s Heart by Gary Paulsen is not an easy book to read, but this novel about 15-year-old Charley Goddard, who enlists with the First Minnesota Volunteers at the start of the Civil War and who returns home four years later, forever changed by his experiences, is powerful stuff.

Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts by Rebecca Hall is a fascinating graphic novel history of Black women’s leadership in enslaved people’s uprisings. I learned so much reading this book! Similarly, Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s biography She Came to Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman is a brilliant reminder that Black Americans were fighting against slavery before and during the Civil War.

The lasting impact of the Civil War is the central focus of Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. Though it’s more appropriate for older readers, Horowitz’s journey into the legacy of the Confederacy in the modern-day South raises the kinds of questions that can keep you talking for days.

Movies

Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990) is the undisputed must-see Civil War documentary. Though Burns caught some flack from historians for his“American Iliad,” his epic history of the Civil War is rich with details and emotionally charged. Balance it with thoughtful conversations about slavery and Reconstruction.

Glory (1989) tells the story of the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a platoon of African-American soldiers whose assault on Fort Wagner at the Battle of Fort Wagner helped the Union army win that battle. Though the story is exciting enough to be fiction, it’s firmly rooted in real historical details.

Gettysburg (1993) is based on Michael Shaara’s excellent novel The Killer Angels and was filmed on the battlefields of Gettysburg. The film focuses on the 1863 battle that prompted Lincoln’s famous address. (The follow-up film, Gods and Generals, is worth watching, too, if you want more.)

The tear-jerker ending of Shenandoah (1965) softens the film’s anti-war message, but the toll of war off the battlefield remains a major theme. Jimmy Stewart plays a Southern farmer who wants nothing to do with a war that doesn’t concern him — until his family, like so many families, is affected by the violence of the war.

Online Resources

The Valley of the Shadows project chronicles the history of two communities — Franklin County in Pennsylvania and Augusta County, Virginia — through the years leading up to, during, and following the Civil War. Thousands of primary sources tell the story of what life was like for people living through one of the United States’ most turbulent periods.

It would be hard to overemphasize the importance of the railroad in the progress and outcome of the Civil War, and the digital history project Railroads and the Making of Modern America walks you through the railroad’s role in military and political strategy.

The National Park Service’s Civil War hub has lots of information about the War Between the States, but one of the most practical resources for homeschoolers in search of a field trip is the comprehensive list of Civil War landmarks around the country.

One of the most interesting things about the Freedmen and Southern Society Project is its illumination of the role that slaves themselves played in the emancipation process.

Was the Civil War inevitable? See for yourself, as you face the same choices President Lincoln did in Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads, an interactive game developed by the National Constitution Center.

The 1862 battle at Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg) inspired Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. You can trace the pivotal battle online at Antietam on the Web, which includes handy maps and information about participants on both sides of the field.

Sherman’s march to the sea, cutting a swath of destruction through Georgia and effectively cutting off the Confederate Army, may be one of the best-known campaigns of the Civil War — and you can follow General Sherman’s route on the interactive maps at Sherman’s March and America: Mapping Memory.

The lines between North and South weren’t always as simple to draw as history books suggest, and New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War explores New York’s complex place in the war. The city supported a thriving abolitionist movement even as it relied on slavery-supported economic ties to the South.

Field Trip

Appomattox Courthouse National Historical Park has a full schedule of reenactments, lectures, guided battlefield walks, and more to commemorate Lee’s surrender here 150 years ago.

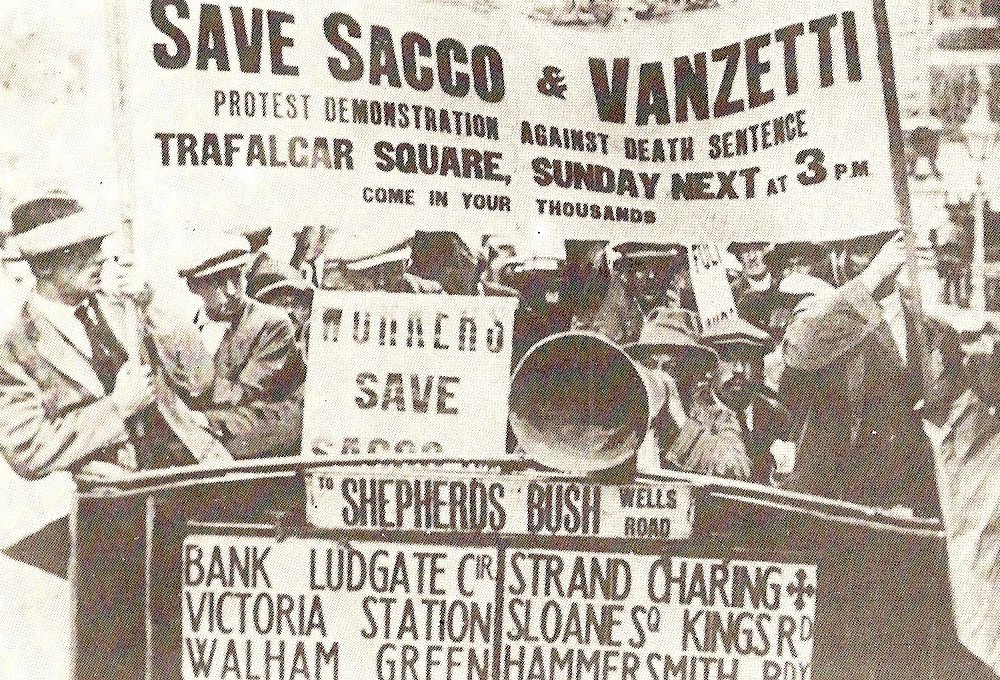

Homeschool Unit Study: The Sacco-Vanzetti Case

One of the most notorious trials of the 20th century United States makes a great starting point for big conversations about racism and the Red Scare.

How impartial is the U.S. justice system really? A deep dive into this notorious 20th century court case gives historical context for that big question.

The Sacco-Vanzetti case, which began in April 1920, remains one of the most controversial and debated cases in U.S. history. Did Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti commit the murder for which they were executed? The answer to that question remains less important than the other questions about immigrants, political opinions, and justice that it continues to raise. This is just one case, but digging into with your high schooler reveals a lot about the United States in the 1920s, anti-immigrant sentiment, and the Red Scare.

The Case:

On April 15, 1920, robbers killed a paymaster and a guard at a shoe factory in South Braintree, Massachusetts before escaping. Suspicion fell on two naturalized Italian immigrants: Nicola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a fish peddler. Sacco and Vanzetti were ideal villains — as atheists, draft avoiders, and anarchists, they represented a triple-threat to American ideas about the importance of religion, country, and property.

The problem was that they might not actually have been villains. Caught up in a maelstrom of prejudice and fear, their case moved rapidly to court and execution, in the end resembling a slow-moving lynch mob as much as an organized pursuit of justice. Neither man had a criminal record, and there was no evidence against them. Another known criminal actually confessed to the crime while the trial was happening. Despite numerous appeals and evidence of the innocence, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed August 23, 1927.

Listen to this: The Past Present: History For Public Radio’s episode on Sacco and Vanzetti includes historical audio of the defendants and other people involved in the case, Woody Guthrie ballads, Italian anarchist songs, and readings from the letters Sacco and Vanzetti wrote from prison. (Scroll to the bottom to download the full program.)

Talking point: Why were anarchists targets for suspicion in the 1920s United States?

Read this: How did people feel about the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti? The New York Times gave them the day’s main headline, and for the first time in modern history, the city of Boston shut down Boston Common in fear that activists would congregate there. The poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, one of many artists who tried to have the verdict overturned, wrote, “[the] men were castaways upon our shore, and we, an ignorant savage tribe, have put them to death because their speech and their manners were different from our own, and because to the untutored mind that which is strange is in its infancy ludicrous, but in its prime evil, dangerous, and to be done away with.’ And the Atlantic Monthly published a long essay by future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter highlighting some of the major problems with the case.

Talking point: How did anti-immigrant sentiment contribute to the sentence in this case? (You may want to look up the immigration quotas of 1924, which passed while Sacco and Vanzetti were in prison.)

Explore this: You can visit the virtual exhibit Sacco & Vanzetti: Justice on Trial from Boston’s John Adams Courthouse online and explore the history and after math of the trial, including court transcripts like this cross-examination of Sacco:

QUESTION: Did you love this country in the last week of May, 1917?

SACCO: That is pretty hard for me to say in one word, Mr. Katzmann

QUESTION: There are two words you can use, Mr. Sacco, yes or no. Which one is it?

SACCO: Yes.

Talking point: Would it have been possible for Sacco and Vanzetti to get a fair trial somewhere else?

Watch this: Tony Shaloub and John Turturro lend their voices to Peter Miller’s 2006 documentary Sacco and Vanzetti, which recreates the trial and incorporates modern forensic evidence.

Homeschool Unit Study: The History of Spies

The end of winter is the perfect time for a secular homeschool unit study that takes a chronological deep dive into some of history's most celebrated spies.

This winter is the perfect time to take a chronological deep dive into some of history's most celebrated spies.

Francis Walsingham (ca. 1532–1590)

Queen Elizabeth’s adviser was the first great English spymaster, and the culmination of his secret intelligence work was the frame-up, capture, and execution of Mary Queen of Scots in 1586. Most of Walsingham’s efforts were directed against the Catholics, whom Walsingham, a staunch Protestant who vividly remembered the Protestant purges initiated by Elizabeth’s sister and predecessor, feared and mistrusted. Walsingham organized a spy network that would impress modern day intelligence agents, complete with forgers who could copy any seal, an army of letter interceptors, complex ciphers to protect his own mail, and spies everywhere.

Read This:

The Queen’s Agent: Francis Walsingham at the Court of Elizabeth I by John Cooper

Benjamin Tallmadge (1778)

The so-called Culper Ring, led by Benjamin Tallmadge, tracked Tory troop activities in British-occupied New York City by actually joining Tory militias, feeding crucial information to the colonial army. They’re also credited with helping to bring down Benedict Arnold.

Read This:

Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring by Alexander Rose

Mary Bowser (1860s)

Mary Bowser joined the Richmond Underground, a movement that worked to get enslaved people, Union prisoners, and Confederate deserters out of occupied Richmond, Virginia. When she managed to get work at the Confederate White House, Bowser was able to pass important confidential information on to the Union.

Read This:

Spy on History: Mary Bowser and the Civil War Spy Ring by Enigma Alberti and Tony Cliff

Belle Boyd (1860s)

The Confederates had their spies, too, and 17-year-old Maria Isabella Boyd was one of them. Under guard for shooting a drunken Union solider who had insulted her and her mother, Belle charmed secret information out of her guard and passed it on to the Confederate troops.

Read This:

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War by Karen Abbott

Sidney Reilly (1890s-1925)

The “Ace of Spies” was the model for Ian Fleming’s James Bond. The handsome, womanizing Russian-born British agent spied on 1890s Russian emigrants in London, in Manchuria on the cusp of the Russo-Japanese War, and participated in an attempted 1918 coup d’etat against Lenin’s Soviet government. Reilly disappeared in the Stalinist Soviet Russia of the 1920s.

Watch This:

Margarethe Zelle (1914-1917)

Better known as Mata Hari, Zelle became one of the most famous spies in history even though chances are pretty good that she never actually did any spying: She was recruited by the French and by the Germans, both of whom saw potential in her globe-trotting work as an exotic dancer, but she doesn’t appear to have given any intelligence to anyone. Still, when the Germans outed her as a double agent, the French had her arrested and executed tout suite, despite a lack of actual evidence.

Read This:

Femme Fatale: A New Biography of Mata Hari by Pat Shipman

Virginia Hall (1930s-1940s)

“The limping lady” — so named because she’d shot herself in the foot and 1932 and replaced her amputated lower leg with a prosthetic limb — volunteered her services as a spy in occupied France, coordinating the activities of the Resistance under cover as a correspondent for the New York Post. Hall’s prosthetic foot, which she named Cuthbert, provided a convenient hiding place when smuggling top secret documents.

Read This:

The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy by Judith L. Pearson

Klaus Fuchs (1940S-1950S)

Fuchs was a nuclear physicist who left Germany in 1933 to come to England, where he worked on “Tube Alloys,” the British atomic bomb project, before joining the Manhattan Project in the United States. Fuchs hated the Nazis, but he had complicated feelings about the post World War II world — which led him to feed information to contacts in the Soviet Union. Fuchs was arrested for espionage in the 1950s and imprisoned.

Read This:

The Spy Who Changed the World: Klaus Fuchs, Physicist and Soviet Double Agent by Mark Rossiter

Melita Norwood (1962-1999)

Norwood worked as the assistant to the director at a British atomic research center for 37 years before her employers realized that she’d been passing secret information from her job on to the Soviets the whole time she’d worked there. By that time, Norwood was an 87-year-old grandmother, whose 1999 arrest made headlines and shocked everyone who knew her — including her family.

Watch This:

Expand your study further with these spy books for kids:

Spy Science: 40 Secret-Sleuthing, Code-Cracking, Spy-Catching Activities for Kids by Jim Wiese

How to be an International Spy: Your Training Manual, Should You Choose to Accept It by Lonely Planet Kids

DK Eyewitness Books: Spy: Discover the World of Espionage from the Early Spymasters to the Electronic Surveillance of Today by Richard Platt

World War II Spies (You Choose: World War II) by Michael Burgan

Homeschool Unit Study: The History of Cuneiform

Ancient Mesopotamia’s writing system offers a peek into geography, history, culture, and class in the ancient world. Learn more with a secular homeschool unit study for middle and high school students.

Ancient Mesopotamia’s writing system offers a peek into geography, history, culture, and class in the ancient world. Learn more with a secular homeschool unit study.

Some time between 522 and 486 B.C.E., a patient scribe carved the story of the rise of Darius the Great into a cliff in western Iran, not once but three times in three different cuneiform script languages. The finished inscription is 49 feet high and 82 feet wide, a virtually indelible record of the triumph of the most famous man in the world at the time — but it would be more than 2,000 years before any English-speaking historian could read it.

Cuneiform, along with Egyptian hieroglyphics, is one of the two most ancient written languages in human history. The birth of writing 5,500 years ago in ancient Sumeria was probably born of economic need instead of creative energy: The earliest written records, tokens made of stone or clay, record business transactions. Later, these tokens became pictographs, symbols inscribed on clay tablets that represented numbers or objects. Gradually, these symbols became more complex and sophisticated, and writing became about telling stories as much as about conducting business. By the time cuneiform faded from use — around the first century C.E. — people used it write letters, do schoolwork, write religious texts, and more.

Unlike an alphabet, cuneiform uses between 600 and 1,000 characters to write words or syllables — which may help explain why it was so difficult for Western readers to discover. To read it, you have to learn the language being recorded and then all the signs, which tend to have multiple possible meanings. Like other languages, cuneiform seems to be easier for children to pick up than for adults — many of the surviving cuneiform documents we have today are actually spelling and handwriting exercises probably done by Sumerian students.

Part 1: How Cuneiform Works

Do this:

Try this:

Pretend the alphabet doesn’t exist, and you have to invent a form of writing based around simple pictures. Brainstorm a basic system, and see if you can use it to write:

your name

a verb (like dance or read)

adjectives (like delicious or fun)

Talk about this:

What does picture writing do well? What are some advantages it might have? What limitations does picture writing have?

What is the purpose of writing? Think about commercial reasons (like buying and selling), political reasons (writing laws or training an army), and social reasons (telling stories or organizing religions).

Part 2: The Story of Writing

Do this:

Work through the interactive online activity The Story of Writing, which explores the development of the cuneiform character for barley over time.

Talk about this:

How does the development of the symbol for barley show how cuneiform evolved over time?

Think about this:

Why did the ancient Mesopotamians simplify their pictographs over time? How might this make writing faster or easier? What might be the implications of changing from direct representation (pictures) to abstract representation? (Think about who has access to education.)

Part 3: Writing as Artifact

Talk about:

Cuneiform gives us an idea of what life was like in ancient Mesopotamia and about what kind of lives the people from that place and time lived. So what does it tell us about these people that they started writing in order to record agricultural transactions? Why would these records be important? Who would benefit from recording these commercial transactions? (Think beyond the buyers and sellers — how might these records affect things like taxes and services?)

What else might be important to keep records of? (Births, marriages, and deaths? Property ownership? Work contracts? Religious rules and rituals?) How could writing be used to legitimize and extend political power? (Think of the carvings we talked about at the beginning of this unit — what is their purpose? How well did they succeed at accomplishing that purpose?)

Do this:

Explore some of the artifacts in the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute Tablet Collection. What do these artifacts tell you about life in ancient Mesopotamia?

Epidemic!: A Science of Infection Reading List

It's flu season, and we've got a reading list of historical fiction and nonfiction to help you explore epidemics past in your secular homeschool.

It’s flu season, and we've got a reading list of historical fiction and nonfiction to help you explore epidemics past in your secular homeschool.

It’s been more than a century since Mary Mallon (infamously known as Typhoid Mary) was arrested and imprisoned for the second and final time for spreading typhoid through her work as a cook, but 2014’s Ebola crisis and 2020’s COVID outbreak remind us that infectious diseases are anything but history — though their history can make a pretty fascinating course of study. (Not to mention entertaining reading if you do find yourselves spending a lot of time in doctors’ waiting rooms this winter.) My high school biology curriculum spends the second semester focused on epidemiology, and while we’ve picked Pale Rider and the Spanish influenza outbreak of 1918 as our area of focus, any of these books would make for fascinating homeschool science literature.

The Black Death :: 1348

Record-keeping wasn’t centralized in the 14th century, but historian estimate that the bubonic-turned-pneumonic plague killed somewhere between 75 and 200 million people in Europe and Asia between 1347 and 1351. (That’s 25 to 50 percent of the population at that time — yikes.) The situation was so bad that the word quarantine was coined then, referring to the 40-day offshore waiting period the city imposed on incoming ships.

In The Doomsday Book, 22nd century historian Kivrin travels back to the Middle Ages on a research project, but instead of ending up at the turn of the century, she finds herself in 14th century England right at the beginning of the plague outbreak. She’s got all the relevant shots and training, but nothing could have prepared her for the devastation of life in plague-time.

The Great Plague :: 1665

The last of the great plague epidemics in England ended a wave of outbreaks that had been going on since 1499 and may have killed as much a quarter of 17th century London’s population. (Historians estimate that between 75,000 and 100,000 people out of London’s 450,000 population perished during the outbreak.)

At the Sign of the Sugared Plum tells the story of the plague’s last outbreak in 1665 London. Country girl Hannah is thrilled to come to work in her sister’s candy shop in bustling London, but the looming menace of the plague slowly seeps into everyday life. (I especially liked that the chapters began with bits from Pepys’s Diary.)

When a bolt of infected fabric from London was delivered to the village of Eyam north of the city, the townsfolk there voluntarily sealed themselves off from the rest of the world to prevent the spread of the plague. (Their decision probably saved thousands of lives, though it was a death sentence for many of the people who lived there.) The Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague is set in Eyam during this time and told from the perspective of a young housemaid who sees both the incredibly generosity and kindness and the cruelty and horror of people faced with almost certain death.

If you’re not plague-d out yet, Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year records his family’s memories of the plague year. (Defoe was only five years old during the outbreak.) The recentness of the events comes through in the details.

Yellow Fever :: 1793

Almost a tenth of the population of Philadelphia died during the yellow fever epidemic before a cold front helped take out the infected mosquitoes that carried it. The first cases of yellow fever were reported in the summer of 1793; by mid-October, the “American plague” was killing 100 people a day.

Laurie Halse Anderson makes the history personal in Fever: 1793. Fourteen-year-old Mattie is working hard to make her family’s small coffee shop a success, but when her family servant and friend dies of the fever and her mother becomes ill, Mattie and her grandfather join the scores of people fleeing the city. Things don’t go as planned, and when Mattie finally finds her way home, nothing is the same.

Cholera :: 1854

What’s great about London’s 1854 outbreak of cholera — no, really, bear with me! — is that it’s one of the first times an epidemic got shut down by science. John Snow, an anesthesiologist, theorized that cholera was spread by infected water not bad air, as current science suggested. As the outbreak raged, Snow tested his theory on the ground, successfully proving that a contaminated pump was the root of the problem.

The Great Trouble: A Mystery of London, the Blue Death, and a Boy Called Eel is historical fiction for the science geek, as a mudlarking orphan helps physician John Snow work to determine the true cause of the cholera epidemic attacking the city. My students also dig The Ghost Map, a nonfiction account which treats the outbreak like a scientific mystery.

The Plague :: 1900

Did you know that the plague struck the United States in the early 20th century? A ship from Hong Kong brought the plague to San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1899, and though official channels denied it for public relations reasons, 119 people died before a change in policy effected medical treatment for those affected.

In Chasing Secrets, a 13-year-old girl, who’d rather go on calls with her doctor father than learn how to be a proper young lady at her fancy private school, gets to put her scientific knowledge to work trying to figure out what’s causing the quarantine in Chinatown so that she can help her new friend save his father.

Typhoid :: 1906

A New York cook named Mary Mallon became one of the first people caught at the intersection of emergency health measures and the right to privacy when she was discovered to be the cause of an outbreak of typhoid in a Long Island enclave. A carrier of the disease who also happened to be immune to it, Mallon refused to comply with health officials’ orders designed to stop the disease from spreading — she seems to have found it impossible to believe that a perfectly healthy person could infect other people — and ended up spending 25 years in medical isolation.

Deadly imagines what it was like to track the New York typhoid epidemic as a young scientific researcher. Prudence is thrilled to find a job in an actual laboratory — no easy task for a graduate of Mrs. Browning’s esteemed School for Girls — and even more thrilled when she gets to participate in real, important research tracking down the source of a typhoid epidemic. But when the source in question turns out to be an ordinary human being, deciding what to do next gets complicated.

For a nonfiction breakdown of the cholera outbreak, Fatal Fever: Tracking Down Typhoid Mary focuses most of its attention on Mallon but also includes information about cholera’s pre-20th century significance and modern-day cholera science.

Spanish Influenza :: 1918

More people died in the flu outbreak of 1918-19 than in World War I — an estimated 50 million people died of the flu, and more than one-fifth of the world’s population was affected by the outbreak. In one year, life expectancy in the United States dropped by 12 years.

American Experience: Influenza 1918 offers a fascinating look at the mysterious and deadly 20th century influenza epidemic, starting with the first case reported in a Kansas army hospital and continuing until the epidemic’s unexplained end.

Gina Kolata paints the history of the influenza outbreak as a scientific detective story in Flu: The Story Of The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It.

Like the Willow Tree: The Diary of Lydia Amelia Pierce, Portland, Maine, 1918, part of the Dear America series, demonstrates how completely the influenza epidemic changed people’s lives. Lydia and her brother move from their comfortable Portland neighborhood to a Shaker community with their uncle after their parents die from the flu.

Polio :: 20th century

Polio’s highly infectious nature allowed it to sweep through towns and cities almost unchecked, making it one of the most feared epidemics of the 20th century. In 1952 alone, almost 60,000 children had polio; of those, more than 3,000 died and many were left with permanent disabilities.

In Risking Exposure, it’s Sophie’s experience with polio that leads her to recognize the evil of the Nazi regime in Germany. Though she survives and is given a job as a state photographer, she’s horrified to see pictures of her fellow polio survivors used to mock people with disabilities.

To Stand On My Own: The Polio Epidemic Diary of Noreen Robertson, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 1937 is set during Canada’s Great Depression, when things are hard enough without polio. When Noreen contracts the disease, her family sends her away to recover, first to the local hospital, then to a farther-away treatment center. The stories of medical wards and patients struggling to walk again reflect the very real experiences of childhood polio survivors.

For a personal account of surviving polio, pick up Small Steps: The Year I Got Polio.

Homeschool Unit Study: The Harlem Renaissance

Black History Month is the perfect excuse to celebrate the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African-American culture that lit up the creative landscape of the 1920s with its epicenter firmly located in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood.

Black History Month is the perfect excuse to celebrate the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African-American culture that lit up the creative landscape of the 1920s with its epicenter firmly located in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood.

Jacob Lawrence, 1917-2000, To Preserve Their Freedom, from Toussain L'Ouverture series, serigraph, 1988-1997. Museum of Arts & Sciences, Daytona Beach.

The Harlem Renaissance is one of my favorite periods of U.S. history to explore in our high school homeschool. My students get excited by the sheer abundance of possibilities: You’ve got art, you’ve got literature, you’ve got music, you’ve got social criticism, you’ve even got food. On apparently every front, Black Americans were bringing their culture and creativity into play, and the result is almost an embarrassment of riches. There are several directions you could go with this unit: Treat it as a literature unit, and dive into some of the period’s most important works, or use it as a jumping-off point for a big, interdisciplinary study of early 20th century African American history. We usually do the latter, since the Harlem Renaissance also provides an impetus and meaningful background for the civil rights movements of the mid-20th century.

READ

Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois

The sociologist and activist W.E.B DuBois was in many ways the father of the Harlem Renaissance, and in this, his most important work, DuBois makes a claim for re-thinking of African-American identity that was to resonate with a generation of African-Americans. DuBois was himself a remarkable figure — the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University, he wrote many books, founded the Niagara movement, which opposed Booker T. Washington’s policies of conciliation, and fought for the rights of African-Americans to vote and enjoy the same privileges as other Americans. Souls of Black Folk memorably and movingly describes DuBois’ dawning awareness of his “double consciousness” as an African-American, “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

“The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” by Langston Hughes

One of the central debates of the Harlem Renaissance was the question of what art, specifically African-American art, was meant to do. Should the concern of black artists be to counter white stereotypes or simply to portray black life as realistically and authentically as possible? While DuBois thought the former, a younger, more militant generation of black artists, most prominent among them the poet and novelist Langston Hughes, aimed to show all of Black life in their art. In this essay, published in the Nation magazine in 1921, Hughes criticizes those middle-class Blacks who are ashamed of their race and calls on African-Americans to embrace their own heritage and “indigenous” art forms, such as jazz.

Cane by Jean Toomer

Blending poetry with sketches of black life in the South and North, Toomer’s Cane is one of the literary masterpieces of the Harlem Renaissance. Toomer was a racially mixed man who could pass as white and, according to Henry Louis Gates and Rudolph P. Byrd, often chose to.

Every Tongue Got to Confess: Negro Folk-Tales From the Gulf States by Zora Neale Hurston

Though best-known for the classic (and staple of high school English curricula) Their Eyes Were Watching God, Hurston began her career carrying out anthropological field work in the South. This collection of her sketches from her travels in Florida, Alabama, and New Orleans show how central the African-American experience in all parts of the United States, not just in Harlem, were to members of the Harlem Renaissance

LOOK

Carl Van Vechten

Van Vechten was one of the most unusual figures of the Harlem Renaissance. A prototype of what Norman Mailer would later call the “White Negro,” Van Vechten saw himself as a champion of African-American culture, and though his involvement in the movement was controversial, he was instrumental in bringing the work of African-American writers and artists to a wider public. A novelist, dance critic, and Gertrude Stein’s literary executor, he also photographed many of the Harlem Renaissance’s prominent figures, including DuBois and Zora Neale Hurston.

Aaron Douglas

The visual arts were central to the Harlem Renaissance, and Douglas’s African-influenced modernist murals caught the attention of the leading intellectuals of the movement like Alain Locke and W.E.B DuBois. Douglas’s best-known work were the illustrations he created for James Weldon Johnson’s books of poetic sermons, God’s Trombones.

LISTEN

“Prove It On Me Blues” Ma Rainey

Big, bold, and fearless, Ma Rainey was one of the first female blues singers to achieve fame. Though she didn’t have a great voice, Rainey delivered the double entendre-laden lyrics of her songs with a power and intensity that paved the way for later female singers like Bessie Smith. Here, Rainey sings in remarkably bold terms about her romantic pursuit of a woman, and of her preference for lesbian relationships. The theme of homosexual love was central to the Harlem Renaissance, the historian Henry Louis Gates even arguing that the movement “was as much gay as it was black.”

“T’aint Nobody’s Business if I Do” Bessie Smith

More than any other singer, Bessie Smith embodied the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance — its emphasis on race pride, its uncompromising view of the value of African-American lives.

“Black and Blue” Louis Armstrong

Originally written by Fats Waller for the musical Hot Chocolates, “Black and Blue” became, in Louis Armstrong’s hands, a defiant statement on what it was like to be black in America (Ralph Ellison riffs poetically on the song in his great novel Invisible Man.)

WATCH

The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross

Henry Louis Gates’ sweeping survey of African-American history provides a good general background to the movement and his section on Black popular arts and film of the 1920s is particularly helpful.

Against the Odds: Artists of the Harlem Renaissance

Focusing mainly on the visual arts, this documentary shows how art and politics were inextricably linked for members of the Harlem Renaissance.

Langston Hughes’ “The Weary Blues”

Jazz cadences and rhythms can be found throughout the poetry of Langston Hughes and in this spoken reading, Hughes reads his own poetry to jazz accompaniment, from a broadcast of The 7 O’Clock Show, 1958.

A Note About Affiliate Links on HSL: HSL earns most of our income through subscriptions. (Thanks, subscribers!) We are also Amazon affiliates, which means that if you click through a link on a book or movie recommendation and end up purchasing something, we may get a small percentage of the sale. (This doesn’t affect the price you pay.) We use this money to pay for photos and web hosting. We use these links only if they match up to something we’re recommending anyway — they don’t influence our coverage. You can learn more about how we use affiliate links here.