Unit Study: Exploring the French Revolution

By the time the French Revolution ended, the class and political landscapes of the Old World has been completely redrawn to value democratic political participation and individual rights. All of this makes it a particularly fascinating period of history to dig into with your high schooler.

The rise of the proletariat launched the bloody end of the Old World and the beginning of a new one, and most people date the revolution’s official beginning to the opening of the Estates General, on May 5, 1789.

The French Revolution was the 18th century revolution that mattered. Across the Atlantic, the revolt of Britain’s colonies raised a few eyebrows, but it was the revolution in France that reshaped the European world. When the revolution began, Europe was dominated by virtually impenetrable class structures and wealthy aristocrats; by the time the French Revolution ended, the class and political landscapes of the Old World has been completely redrawn to value democratic political participation and individual rights. All of this makes it a particularly fascinating period of history to dig into with your high schooler.

SET THE STAGE

To appreciate the impact of (and motivation for) the French Revolution, you need to understand the world that preceded it. A big piece of that world is the pre-Enlightenment notion of royalty, captured in candy-colored opulence in the film Marie Antoinette. As you watch it, talk about the expectations of royalty: They really believed they ruled because some divine being wanted them to and had no problem living the high life regardless of the conditions in which their citizens were living. Were they evil or just completely oblivious? You can decide for yourself. And then you can watch 1938’s La Marseillaise to see the beginnings of this world’s unravelling.

CONSIDER THE SCOPE

Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities carries the reader from the first rumblings of the French Revolution to its bloody, battered climax through the story of two lookalikes who find themselves at the center of revolutionary action. As you read, think about how the revolutionaries are perceived — and how their aims and actions change over the course of the story. How do passion-fueled individuals become a violent mob?

For a non-fiction take, Alexis de Tocqueville’s The Ancien Régime and the Revolution isn’t a contemporary account (Tocqueville was born in 1805), but it’s a near-contemporary look at both the promise of democracy and the failures of democracy leading up to and in the wake of the French Revolution. As you read, think about what interests Tocqueville so soon after the revolution: How did this happen?

Finally, pick up The New Regime by Isser Woloch — it’s a bit staid, but it does a great job chronicling the Revolution’s major, world-changing effects (for better and worse). Divorce, universal education, revised penal codes — as you read, make a list of all the things we now take for granted that originated with the French Revolution.

GET PERSONAL

Once you’ve got a handle on the story of the Revolution, slow down and explore its impact on individual lives. You’ll probably have to read the subtitles, but the French film Danton, depicting the last weeks of Revolution hero-turned-public enemy number one Georges Danton, offers a meaningful look at the dark side of the Revolution (with a bonus commentary on late 20th century Poland). Think about the nature of betrayal in a world of shifting allegiances and power. Get outside of Paris with Daphne du Maurier’s The Glass Blowers, which focuses on the brutal royalist counter-revolution in the 1790s. The Broussard family (based on du Maurier’s real-life ancestors) are caught up in the prospect of revolutionary changes but find it hard to adjust to post-war hardships.

Unit Study: Queen Victoria

You could spend years digging into the life of the British ruler who gave the Victorian age its name and still make new discoveries, but consider these resources a delightful starting point for a high school history homeschool unit study.

Celebrate Victoria Day on May 22 by learning more about the British queen it’s named for.

When Alexandrina Victoria took the throne of England in 1837, she was a teenager inheriting a seriously tainted monarchy. By the time of her death in 1901, the Queen had become a global symbol of the British Empire, the time period had become eponymous with her name, and she would successfully redefine royalty for the modern world. Some of this was luck, some of this was the people who surrounded her, and some of it was the sheer stubborn determination of Victoria herself. You could spend years digging into Victoria’s life and still make new discoveries about the 19th century queen, but consider these resources a delightful starting point.

READ

Who Was Queen Victoria? BY JIM GIGLIOTTI

This is a predictably solid entry in the reliable Who Was elementary biography series, covering Victoria’s life from unhappy childhood to triumphant Jubilees. (Elementary)

My Name Is Victoria BY LUCY WORSLEY

Worsley imagines Victoria’s life through the eyes of her forced companion, John Conroy’s daughter — also named Victoria — who is brought to Kensington Palace to spy on the Queen-to-be but finds herself sympathetic instead. (Elementary)

Victoria: May Blossom of Britannia, England, 1829 BY ANNA KIRWAN

This historical fiction novel is part of the Royal Diaries series, so its focus is on Victoria’s unhappy princess period, when she dreams of being Queen as a way to escape her miserable life at Kensington Palace. (Middle grades)

Victoria Victorious BY JEAN PLAIDY

Jean Plaidy is less sparkly than usual in this historical novel, and like so many writers, she dwells on the romance of the early half of Victoria’s reign, when she is a young queen in love with her husband, but this first-person story is a thoughtfully researched introduction to Queen Victoria’s life. (Middle grades)

Queen Victoria BY LYTTON STRACHEY

For the post-World War I view of Queen Victoria, turn to Lytton Strachey’s very un-Victorian biography, a classic, snarky history as full of royal gossip as historical details. (High school)

Victoria BY DAISY GOODWIN

This YA-friendly historical fiction biography focuses on Queen Victoria’s first two years as Queen of the British Empire, bringing to life the larger-than-life personalties who defined the early years of her reign, including the very charismatic prime minister Lord Melbourne, Victoria’s cousin (and future husband) Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Victoria herself. (High school)

Victoria: The Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire BY JULIA BAIRD

If you’d like a frothy biography that reads like a well-researched version of “Keeping Up with the Hanovers,” pick this up: Baird writes a little like a romance novelist and holds firm to her theory that Victoria secretly married her servant John Brown, but it’s a fun read. (High school)

We Two: Victoria and Albert: Rulers, Partners, Rivals BY GILLIAN GILL

Even though Victoria reigned for half her life without Albert, his influence on her was so great that he permanently shaped her ideas (for better and worse) about what a monarch, a parent, and a woman should be. This dual biography illuminates the most important relationship of Victoria’s life and the constant tension between power and family love that it inspired. (High school)

Victoria’s Daughters BY JERROLD M. PACKARD

It was not easy to be the offspring of the ruler of the British Empire and her perfectionist partner, and this group biography explores the lives of the five women who called Queen Victoria mother. It’s a sad and fascinating history of female life on top tier of British society, with a special interest in the life of rebellious Princess Louise. (High school)

Uncrowned King: The Life of Prince Albert BY STANLEY WEINTRAUB

I’m always telling my students that had Albert lived as long as his wife, we would probably be calling the 19th century the Albertine Era. Weintraub does a great job painting a vivid picture of the reform-minded, ethically intense polymath who proved the perfect romantic and political partner for the woman he was steered to marry since childhood. (High school)

The Letters of Queen Victoria BY QUEEN VICTORIA

One of the best ways to get to know someone is through her own words, and Victoria is no exception. The Letters of Queen Victoria put the Queen’s best foot forward, clearly demonstrating how the chief figure of the Victorian era wanted to be seen by the people in her world. (And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that her children re-edited these letters, too.) (High school)

WATCH

Victoria

Jenna Coleman’s Victoria is neither prim nor proper, but she’s certainly interesting in this fairly faithful BBC adaptation created by Daisy Goodwin. OK, it veers a little toward the romantic with heartthrobs cast as middle-aged Melbourne, aristocratic Albert, et al, but who are we to complain about a little eye candy in period costume?

The Young Victoria

Emily Blunt is the lonely little girl crowned Queen of England in this dreamy biopic focused on the years 1836 to1840. Paul Bettany is a particularly disreputable Lord Melbourne, Mark Strong is a particularly vile John Conroy, and Miranda Richardson is a conflicted Duchess of Kent, but Blunt steals the show with her Victoria torn between the desire for freedom and independence and longing for a real family.

Victoria the Great

This 1937 film focuses on the early years of Victoria’s reign. The film, commissioned by Edward VII in honor of his great-grandmother, includes sets and costumes that are accurate reproductions of actual items in the British museum.

Mrs. Brown

Judi Dench is glorious as a middle-aged Victoria who cannot seem to get her Queenly groove back after the death of Prince Albert. Only Albert’s Highland servant, John Brown, cheers her up, but friendship between a Queen and a rowdy Scotsman seems pretty scandalous.

Victoria and Abdul

Judi Dench reprises her role as Victoria in another historical account of the Queen’s fondness for her servants: This time, it’s focused on Victoria’s late-in-life friendship with her Indian servant Abdul Karim.

Ohm Krüger

For a totally different perspective, screen this World War II German propaganda flick about the Boer War, which paints Queen Victoria as a ruthless alcoholic who tricks the Germans into signing an unfair treaty.

PBS Empires: Queen Victoria

This series focuses on the politics and geography of the Victorian empire, which ruled one-fifth of the world’s people during Victoria’s 64 years on the throne.

Homeschooling With Movies: Using Hitchcock to Teach Literature

A combination of watchability and intelligence make Hitchcock a great starting point for serious cinema studies — and for applying critical reading techniques to a text that isn’t a book.

When Vertigo premiered 60 years ago this May, Alfred Hitchcock cemented his reputation as one of the 20th century’s great filmmakers. This spring is an ideal time to explore his work with its complex themes of control, identity, and connection.

So many of the things we take for granted in the world of cinema comes from obsessive auteur Alfred Hitchcock: those stomach-twistingly abrupt edits, the unadulterated pleasure of voyeuristic shots, the camera that roves dreamily but inevitably through the landscape, and that eyeline match that pulls the object of desire directly into your gaze. Hitchcock was notoriously difficult: His complex, controlling treatment of women, his micro-focus on every detail, his puppetmaster management of scenes and characters — all of these find their way into his films. But Hitchcock wasn’t just a cinematic genius. His movies also had tremendous popular appeal, spurring film critic Andrew Sarris to say, wryly, that “Hitchcock's reputation has suffered from the fact that he has given audiences more pleasure than is permissible for serious cinema.” That combination of watchability and intelligence make Hitchcock a great starting point for serious cinema studies.

WATCH REAR WINDOW and Talk about the Elements of Suspense.

The film’s protagonist Jeff is stuck in his apartment in a cast, so we’re stuck with him in his claustrophobic housebound perspective. Notice how Hitchcock slowly builds the tension — first, our curiosity is piqued as we watch Jeff ’s neighbor-across- the-way’s suspicious behavior. Then, curiosity turns to fear when we, with Jeff, watch his girlfriend search the apartment. We know, with Jeff, that the man is on his way back, but like Jeff, we’re powerless to warn Lisa. All that suspense builds to a fever pitch after Jeff loses sight of the man and we realize that the villain is coming after chair-bound Jeff. The genius of these scenes lies in Hitchcock’s focus on the narrow perspective of the protagonist: Like Jeff, we’re voyeurs who see more than we bargained for. Hitchcock manipulates us into complicity with Jeff ’s voyeurism — and by extension, his peril. Jeff is our cinematic stand-in — we’re not sure whether he’s imagining a murder to entertain himself or whether he’s truly witnessed something terrible, but that’s because we’re not certain of our own intentions.

Watch NORTH BY NORTHWEST and Talk About Setting the Scene.

One of the most visceral cinematic moments in North by Northwest comes in the middle of nowhere. Cary Grant’s suave businessman finds himself in the middle of a midwestern cornfield, a stark contrast to the busy city where his story begins. There, people and cars are so commonplace that no one notices them, but pay attention to how this changes once the bus drops him at this lonely out- post: Suddenly every car becomes imbued with meaning, promising danger or hope. With the protagonist, we’re screening the long, flat landscape for lurking danger, and like the protagonist, we’re shocked when it appears from the place we least suspect.

Watch VERTIGO and Talk about Psychology as Plot.

Casting Everyman Jimmy Stewart as the lead in Vertigo was a brilliant ploy on Hitchcock’s part: As soon as we see Stewart’s craggy, earnest face, we know we’re looking at the moral center of the movie. This is the guy we’ll cast our lot with. Except, in Vertigo, we’re wrong. We’re expecting Scotty to repair the damage he did at the beginning of the film when his acrophobia caused another police officer’s death or to somehow save the doomed woman whose suicide he couldn’t prevent. Instead, he spirals (just as the movie’s name suggests) further and further into twistier and twistier obsessions. Notice how Stewart’s psychology drives the plot, his obsessions echoing the role of director as he casts, trains, and observes his ice-blond leading lady — just like Hitchcock himself. The film is both a sly nod to Hitchcock’s reputation and a study in obsessive psychology.

Watch PSYCHO and Talk about Surprising the Audience.

Hitchcock’s version of a horror flick changed movies forever. Though countless other movies have followed its unpredictable twists and harrowing notion of purposeless evil, when Hitchcock (spoiler) sent his leading lady to her doom halfway through a perfectly plotted storytelling session, he shook not just the audience but the entire notion of cinematic narrative. Once the main character dies, the audience has no idea what might happen next. The whole idea of a story with a beginning, middle, and end is disrupted when Janet Leigh dies and the movie continues on without her. It’s a sudden, vicious transition that keeps us unsettled for the rest of the film. The film’s double twist, when (spoiler again) the monster is revealed, looking nothing like a Mr. Hyde or Frankenstein’s Monster but surprisingly like any one of us, is as unexpected as everything else—but also surprisingly right. In the post-World War II world, the notion that evil was not an outside force but a force within us is both shocking and utterly appropriate.

Want more? Hitchcock has inspired filmmakers for decades, but these modern movies really channel his spirit.

Source Code (2011): Jake Gyllenhaal stars in this twisty North by Northwest-ish thriller about a man whose

consciousness travels back in time with eight minutes to stop a deadly accident.

Shutter Island (2010): This noir-ish movie captures Hitchcock’s uneasy realities — right down to the (spoilers) twist ending.

Frantic (1988): Harrison Ford stars as a man whose wife disappears from their Paris hotel room after she accidentally picks up the wrong suitcase at the airport.

High Anxiety (1977): Hitchcock himself loved Mel Brooks’ spoof of his trademark style, jam-packed with wink-wink homages to Hitchcock’s best known films and featuring a theme song worth the price of admission all by itself.

The Spanish Prisoner (1997) David Mamet’s witty, fast-talking movie about corporate espionage owes a huge debt to Hitchcock’s unpredictable narrative twists and turns.

Homeschool Unit Study: The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

Books

Albert Marrin’s Civil War trilogy — Commander in Chief: Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, Unconditional Surrender: U.S. Grant and the Civil War, and Virginia’s General: Robert E. Lee and the Civil War (though this one is a little more apologist for Lee than I prefer)— makes a great read aloud spine for your Civil War studies if you are interested in the war part of the Civil War. Marrin does an excellent job illuminating the personalities and events of the Civil War while still presenting a straightforward, chronological history of the war.

Janis Herber’s The Civil War for Kids: A History with 21 Activities includes hands-on projects like making butternut dye (used by Confederate soldiers on their uniforms), baking hardtack (a food staple for soldiers in the fields), and decoding wigwag (a flag system used to pass messages long distances during the Civil War). This is written for younger students, but I find that high schoolers enjoy a few hands-on activities in their history studies, too.

How can neighbors fight on different sides of the same war? Harold Keith’s Rifles for Watie does a nice job illustrating the complexities of the war through the experiences of fictional Kansas teenager Jefferson Davis Bussey, who finds himself fighting for both the Union and Confederate armies over the course of the war. Keith also focuses his narrative on the war’s western front, which may not be as familiar to younger historians.

The Civil War was the first technology-assisted war, and new weapons, communication devices, and transportation systems played a significant role in the war’s outcome. In Secrets of a Civil War Submarine: Solving the Mysteries of the H. L. Hunley, Sally Walker explores the history of the Confederate submarine that became the first submarine to sink a ship in wartime — though it never resurfaced after the battle. Walker tackles both the science and history of the submarine’s Civil War days and the modern-day forensic work of discovering and investigating the sunken vessel.

Talking about slavery can be one of the hardest parts of studying the Civil War with your kids. Many Thousand Gone: African Americans from Slavery to Freedom by Virginia Hamilton manages to tackle to subject with a rare combination of sensitivity and thoroughness.

When Steve Sheinkin was writing history textbooks, he hated that the most interesting bits always seemed to get left out. He cheerfully remedies that problem in Two Miserable Presidents: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You about the Civil War, an engrossing, anecdote-rich history of the War Between the States that’s equal parts smart and surprising.

Irene Hunt’s Across Five Aprils focuses on life on the homefront. There are no heroic charges or dramatic battles for teenage Jethro Creighton, just the increasingly difficult task of keeping the family farm going while his brothers are away fighting in the Civil War.

In the Shadow of Liberty by Kenneth C. Davis isn’t just about the Civil War — but its collected biographies of Black Americans who were enslaved by former U.S. Presidents illuminate the hypocrisy lurking behind “the land of the free.” This book is an important reminder that talking about the Civil War without talking about how the United States justified, protected, and relied on slavery kind of misses the point.

Paul Fleischman’s Bull Run is a collection of sixteen monologues reflecting the personal experiences of people of different ages, races, genders, and regions during the First Battle of Bull Run.

Soldier’s Heart by Gary Paulsen is not an easy book to read, but this novel about 15-year-old Charley Goddard, who enlists with the First Minnesota Volunteers at the start of the Civil War and who returns home four years later, forever changed by his experiences, is powerful stuff.

Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts by Rebecca Hall is a fascinating graphic novel history of Black women’s leadership in enslaved people’s uprisings. I learned so much reading this book! Similarly, Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s biography She Came to Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman is a brilliant reminder that Black Americans were fighting against slavery before and during the Civil War.

The lasting impact of the Civil War is the central focus of Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. Though it’s more appropriate for older readers, Horowitz’s journey into the legacy of the Confederacy in the modern-day South raises the kinds of questions that can keep you talking for days.

Movies

Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990) is the undisputed must-see Civil War documentary. Though Burns caught some flack from historians for his“American Iliad,” his epic history of the Civil War is rich with details and emotionally charged. Balance it with thoughtful conversations about slavery and Reconstruction.

Glory (1989) tells the story of the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a platoon of African-American soldiers whose assault on Fort Wagner at the Battle of Fort Wagner helped the Union army win that battle. Though the story is exciting enough to be fiction, it’s firmly rooted in real historical details.

Gettysburg (1993) is based on Michael Shaara’s excellent novel The Killer Angels and was filmed on the battlefields of Gettysburg. The film focuses on the 1863 battle that prompted Lincoln’s famous address. (The follow-up film, Gods and Generals, is worth watching, too, if you want more.)

The tear-jerker ending of Shenandoah (1965) softens the film’s anti-war message, but the toll of war off the battlefield remains a major theme. Jimmy Stewart plays a Southern farmer who wants nothing to do with a war that doesn’t concern him — until his family, like so many families, is affected by the violence of the war.

Online Resources

The Valley of the Shadows project chronicles the history of two communities — Franklin County in Pennsylvania and Augusta County, Virginia — through the years leading up to, during, and following the Civil War. Thousands of primary sources tell the story of what life was like for people living through one of the United States’ most turbulent periods.

It would be hard to overemphasize the importance of the railroad in the progress and outcome of the Civil War, and the digital history project Railroads and the Making of Modern America walks you through the railroad’s role in military and political strategy.

The National Park Service’s Civil War hub has lots of information about the War Between the States, but one of the most practical resources for homeschoolers in search of a field trip is the comprehensive list of Civil War landmarks around the country.

One of the most interesting things about the Freedmen and Southern Society Project is its illumination of the role that slaves themselves played in the emancipation process.

Was the Civil War inevitable? See for yourself, as you face the same choices President Lincoln did in Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads, an interactive game developed by the National Constitution Center.

The 1862 battle at Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg) inspired Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. You can trace the pivotal battle online at Antietam on the Web, which includes handy maps and information about participants on both sides of the field.

Sherman’s march to the sea, cutting a swath of destruction through Georgia and effectively cutting off the Confederate Army, may be one of the best-known campaigns of the Civil War — and you can follow General Sherman’s route on the interactive maps at Sherman’s March and America: Mapping Memory.

The lines between North and South weren’t always as simple to draw as history books suggest, and New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War explores New York’s complex place in the war. The city supported a thriving abolitionist movement even as it relied on slavery-supported economic ties to the South.

Field Trip

Appomattox Courthouse National Historical Park has a full schedule of reenactments, lectures, guided battlefield walks, and more to commemorate Lee’s surrender here 150 years ago.

5 Great Poems by Living Poets to Inspire Your High School Poetry Studies

These are the poems that my high school literature students couldn’t stop talking about.

These are the poems that my literature students couldn’t stop talking about.

Students often come into literature classes thinking they hate poetry, but what they really hate is the distance they feel between themselves and “classic poetry.” Sure, you can luck into poems like “The Raven” that feel timeless from the start, but for most people, poetry only becomes interesting when it’s personal, when you personally connect with what you’re reading. And while building your critical reading skills makes any poem fair game for this kind of connection, the process is a lot smoother — and more fun! — if you start with poetry that taps into modern life. That’s why I always try to start poetry classes with living poets. Students are surprised by allusions that they recognize from their own lives, appreciative of relaxed language and syntax, and primed to tackle poetry classics with an energy and curiosity that translates to enjoyment. These are the five poems that always seem to get the process started on the right foot.

I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party BY CHEN CHEN

It hooked them with the Home Alone references, but students really connected with the awkwardness between parents and children trying to bridge the generation gap with love. “This is exactly the kind of stuff that runs through my head when my parents hang out with my friends,” one student said. “I didn't know that was poetry.”

Self-Portrait With No Flag BY SAFIA ELHILLO

My students loved this free-wheeling take on the pledge of allegiance, which inspired them to think about things that anchor their own lives. Drawing connections to everything from the Declaration of Independence to Immanuel Kant, students for the first time actually suggested writing their own poetic pledges. How cool is that?

Playground Elegy BY CLINT SMITH

My class is passionate about social justice, and this slowly unfolding poem about all the things raised arms can mean — from freedom to death — hit them hard. One student texted me on quarantine that her friend was afraid to wear a mask in public because he might be mistaken for a criminal, and she was reminded of this poem. It’s a privilege-shaker in all the best ways.

Ego Tripping (there may be a reason why) BY NIKKI GIOVANNI

As much as the poem itself, I think it was Giovanni’s performance of it that inspired my students — we were lucky enough to get to see her read in person last winter. But even without Giovanni’s sassy-tender reading, the poem’s self-celebrating, feminist retelling of human history is a joyful discovery.

Instructions for Not Giving Up BY ADA LIMÓN

One of the hardest things about studying U.S. history with teenagers is how disappointed they are in the United States. Many of them are seeing for the first time how the big, wonderful ideas of the Declaration and Constitution crumble away if you’re not fortunate enough to be a privileged white male. We hit a point, usually around the civil rights movement, when it just hurts too much — and that’s when I pull out this glorious celebration of hope. Limón’s view of the past as a jumping off point and not a destiny is essentially empowering, just what you need to remind you that every generation has a chance to reinvent the world for the better.

How We Created Our Homeschool’s Studio Ghibli Literature Class (Without a Curriculum)

We used Studio Ghibli's film adaptations of beloved children's books for a secular homeschool high school introduction to comparative literature. Here's how we did it — and how you can, too, no curriculum required.

We used Studio Ghibli's film adaptations of beloved children's books for a high school introduction to comparative literature. Here's how we did it — and how you can, too, no curriculum required.

Literature has always been a no-brainer in our homeschool. My daughter, who is now 15 and who has joked more than once the title of her biography should be Homeschool Experiment in Action is naturally inclined toward language arts, and I’m a well-documented English nerd. We’d never had trouble making a literature class work, and while I was ready to panic about pretty much everything about homeschooling high school, I felt fairly confident that we could handle the literature part.

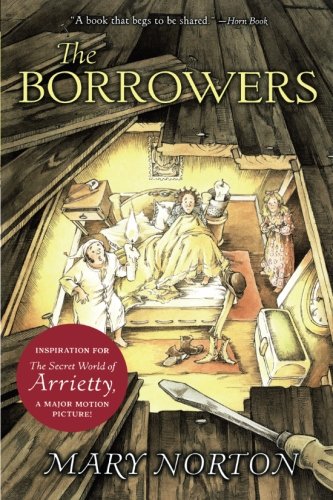

We knew we’d be doing U.S. History this year, and it made sense to weave U.S. literature (along with philosophy, art, and music) into that, but we also wanted to explore comparative literature.1 Comparative literature sounds fancy — and I guess sometimes it can be — but it’s really just looking at works from different cultures, eras, languages, etc., and considering things that are the same and different about them. Adaptations are a great place to start with comparative literature because you’re working from the same source material, which makes it easier to spot similarities and differences, and my daughter had the brilliant idea of focusing on Studio Ghibli films. Several of them are based on books we know and love — The Borrowers, When Marnie Was There, A Wizard of Earthsea, Howl’s Moving Castle — and we thought it could be fun to use these book-film combos as a jumping-off point for in-depth textual analysis.

Maybe somewhere there’s a curriculum that does this, but the great thing about comparative literature is that you don’t need a curriculum — just a willingness to really dig into the text and follow where it leads you. I’m going to break down how we pulled the class together as we went, starting with just a reading/watching list, using one book-movie combo as an example.

This wasn’t our only literature class, and we deliberately chose familiar books for the reading list. Critical reading requires a different set of skills — you’re not just following the story, considering the characters, looking for themes and symbols. You’re pausing to consider why an author might choose a particular word instead of another one, looking behind the curtain of words for what the author doesn’t mention and what that omission might mean, considering what the story you’re reading says about the way the author understood the world. Sometimes it’s easier to do this with a book you know. I often joke with my children that I have to read every book three times because the first time I get caught up in the story, the second time I appreciate all the details I missed the first time, and the third time, I can really dig into the text. Rereading is one of the best tools a critical reader can use. So while elsewhere we’d be focusing on more challenging books, for this class, I wanted to start with the familiarity of rereading.

So we started with The Borrowers, a book we’ve both read many times together and apart. Mary Norton’s tale of tiny people who live in the nooks and crannies of old houses and “borrow” what they need from their larger neighbors is a children’s classic, playing with the idea that the everyday world we inhabit only represents a tiny fraction of what’s going on around us all the time. As we read it, pencil highlighters in hand2, we found lots of things to interest us. Reading it purely for fun3, we’d never really thought about the book in terms of colonialism, but this time, we paid attention to the fact that the events of the book were happening right at the height of the British empire. It was interesting to consider how colonization might reflect the plight of the Borrowers in the book, who — as Arrietty tells the boy — have been growing fewer and fewer.

We also found ourselves talking a lot about who was telling the story and how reliable that person was. Kind of like the world of the Borrowers, the story exists within layers: First, the third-person narrator (who may be grown-up Kate) who introduces Kate and Mrs. May; then Mrs. May, as she tells Kate about her brother; and then, finally, Mrs. May becomes almost an omniscient third-person narrator, describing the thoughts and feelings of her brother, Arrietty, and (to a lesser extent) other characters. How much is Mrs. May imagining or extrapolating based on what her brother told her when he was young? How much did her brother imagine or extrapolate? Who is that first third-person narrator anyway, and why has she picked this story to tell?

With the book fresh in our minds, we were ready to dive into The Secret World of Arrietty, Studio Ghibli’s 2010 adaptation of The Borrowers. Just as with reading, turning a critical eye to cinema usually requires multiple viewings. We watched it once for fun, with popcorn and the whole family, and then again the two of us with our notebooks and pencils in hand.4

The movie moves the action from the Victorian English countryside to modern-day Tokyo, but it generally follows the book’s plot, with Arrietty meeting the human boy (he gets a name in the movie), forging a friendship, and ultimately having to escape with her family from the house and into the world outside when threatened by the exterminator. Taking the story out of Victorian England—basically, the land of fairy tales and whimsy — changes the story immediately, we decided. The Borrowers was written in the 1950s, long after the famously well-mannered society named for Queen Victoria had ended, and setting the story in the past immediately made it plausible: Sure, there might not be tiny people living in houses right now, but there could have been back then, right? Pulling the story into the modern world is insisting on the possibility of magic, which feels like a brave choice.

Then there’s the boy. In The Borrowers , Mrs. May’s unnamed brother is kind of — well — a brat. 5 The movie's Sho (Shawn in the dubbed version) is a nice kid with a serious health condition who’s anxious about an upcoming operation. Why does this change matter so much? After all, in both cases, the plot runs pretty much the same — whether the boy’s encounter with Arrietty and her family changes him or just confirms who he already is doesn’t really significantly affect what happens in the story. One clue, we decided, might lie in the ending. In the book, the story ends abruptly — “and that,” said Mrs. May, laying down her crochet hook, “is really the end.” — but Kate and Mrs. May keep the story going by imagining what the Borrowers’ life in the wild might be like. Like the layered narrators that begin the book, this ending makes The Borrowers as much about stories and how we tell them as about the actual adventures of the Clock family. The movie, on the other hand, begins and ends with the boy’s perspective — the adventure with the Borrowers is just a part of his story. (The dubbed version, especially, emphasizes this with Sho’s voice-over narration that he comes through his surgery fine and enjoys hearing stories about small things disappearing in the neighborhood.) This makes The Secret World of Arrietty a coming-of-age story—Sho’s coming-of-age story.

This, we decided, ties in well with Japanese philosophy, which has borrowed (get it?) ideas from other cultures but always emphasizes the importance of everyday experience. The Borrowers , we decided, continues the West’s long (and often problematic) division between body and mind 6 , so we went back to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave before diving into Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind , which works well as introductory text for considering Zen Buddhism. 7 We worked through these two texts side by side, considering how Plato’s dualism influenced The Borrowers versus how the mindfulness and simplicity of Zen Buddhism informed the Studio Ghibli adaptation. One great example of this we found in the two versions’ treatment of the natural world: In both the book and the film versions, Arrietty yearns for the freedom of the outside world. But while the author of The Borrowers lavishes elaborate descriptions on the minuscule, Victorian-esque home the Clocks have built beneath the floorboards, the world outside remains mysterious — only at the end is there the briefest mention of it. It is, my daughter decided, “an inside book.” The Secret World of Arrietty , however, reads as a love story to the nature world. Its dreamy depictions of elastic orbs of water, spring flowers stretching as tall and far as forests, and drifting petals as seen from Arrietty’s tiny perspective are magical. We see Arrietty through Sho’s eyes, which requires him to put himself in her (tiny) shoes, to change his own perspective.

Similarly, the Clocks are less caricatures and more grounded in Studio Ghibli’s adaptation. Homily is less shrill and panicked, Pod is less Homer Simpson, and Arrietty — who, in the book, sometimes takes risks that just seem incredibly foolish 8 — is brave and adventurous but not reckless. In the book, my daughter pointed out, the Clocks have almost -human names and almost -human homes, and their behaviors feel almost -human, too, often exaggerated to the point of ridiculousness. Though their tininess is even more obvious in the film, the Clocks don’t seem almost -human, like caricatures of everyday people — they just seem like people. We compared this to the Victorian obsession with Japan reflected in art — Tissot’s Young Ladies Looking at Japanese Art is complex and layered, with tons of tiny details that you can tease apart, while Japanese art from the same era is often deliberately simple, focused on capturing a single image, scene, or moment.

There were real similarities between the simple-but-ultimately-more-satisfyingly-complex characterizations in the Studio Ghibli adaptation and the sometimes overwrought-to-the- point-of-stretching-believability characterizations of the Clocks in the novel. We spent a lot of time considering the ways that being able to show Arrietty’s life through the medium of film allowed a more nuanced character development, just as the simpler art left more room for contemplative interpretation.

And that’s really how comparative literature, at its simplest, can work in a homeschool high school. You don’t have to go in with a plan, just with two good texts that you want to consider together. Your plan reveals itself as you explore together—it can point you toward philosophy, science, history, theory, art, music... well, you get the idea. It’s the kind of open-ended inquiry that allows authentic learning—and, honestly, it’s fun.

Nerdy Notes

1 This is obviously a dip-your-toes-in-the-water introduction to comparative literature, not a full or comprehensive exploration.

2 I know, not everyone likes writing in books. I do. But even if I didn’t, I might recommend it for new-to-critical-reading students. The great thing about reading with a highlighter is that you can mark interesting bits as you go — you don’t feel obligated to comment on what makes them interesting, which you might if you were reading with a pencil — and you don’t have to remember what you found interesting, which can be surprisingly hard. It’s easy to flip back through and literally see what sparked an idea.

3 A totally valid life choice

4 It’s a shame that you can’t highlight movies as you go, but we have a little workaround. I start a digital timer when the movie starts, and when we see something we want to go back to, we jot down the time so that we can easily go back and review. If someone gets really excited, we can also just hit pause. (That’s another reason to make your second viewing your academic viewing—you know what happens next, so pausing mid-movie doesn’t ruin the flow.)

5 Speaking of comparative literature, we kept drawing parallels between Brother May and Mary Lennox from The Secret Garden. Both are spoiled kids, reared in India and cross about being in England; both end up finding a purpose that ends up making them kinder, more likable people.

6 I blame Descartes.

7 Japanese philosophy is a gorgeous, complex hodgepodge of Eastern and Western thought, and Zen Buddhism is just a tiny, tiny piece of it. I chose to focus on Zen because I think it embraces a lot of the ideas that carry across Japanese philosophy: respect for nature, compassion, the significance of the everyday world. You could argue that Shintoism or Kokugaku or some other school of thought would have been a better place to start, and I wouldn’t get defensive. This is just where I felt comfortable starting.

8 My daughter insists that this is because her mom, Homily, is constantly panicking about everything so that Arrietty has lost her sense of proportion when it comes to panicking. Homily thinks everything is dangerous, but Arrietty has discovered many things aren’t dangerous, so she assumes nothing is dangerous. I’m glad her dad is the one is giving driving lessons.

Great Short Stories for Your High School Literature Class

Suzanne has the definitive guide to the best short stories for your middle school or high school homeschool (or for your own personal reading list).

Suzanne has the definitive guide to the best short stories for your middle school or high school homeschool (or for your own personal reading list). Bonus: You can read most of them online for free.

As Library Chicken readers may already know, the past year or so of my bookish life has been all about falling in love again with short stories. I was an avid short story reader growing up: I read ghost stories, detective stories, classic stories, and all the science fiction and fantasy I could get my hands on, including everything published in the Big Three magazines (Analog, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine). At some point, however, I lost interest in short stories, preferring the complexity (and longer emotional commitment) of novels, even getting to the point where I actively avoided story collections.

Once I decided to focus on short stories in our homeschool-hybrid junior high literature course, though, I had to start reading and rereading for the syllabus, which led to a binge-read that hasn’t yet tapered off, even as we’re about to wrap up the class. (NOTE: For any interested parties, the list of stories we read during the past semester is included at the end of the post.) For my own sake, I wish I’d rediscovered short stories a while back, but I’m really kicking myself that I didn’t use short stories more while homeschooling my own children.

Short stories are WONDERFUL for homeschool. By their very nature, they’re less intimidating than novels for slower and more reluctant readers (and they don’t interfere as much with the stack of recreational reading that avid readers will already have piled by their bedside), and it’s easier for busy parents to work them in as read-alouds or read-alongs. All of the basic concepts of literary analysis and criticism (setting, protagonist, plot, conflict, etc.) can be practiced with short stories, and it’s easy to read a bunch and build up a ‘mental library’ for the purposes of comparison and contrast. It’s a great way to introduce homeschoolers to classic authors and new genres — and if readers hate them, then the suffering doesn’t last very long! If you haven’t already, I highly recommend trying out some short stories in your homeschool curriculum, and if you’re looking for summer reading ideas now that the school year is winding down, short story collections are a great place to start.

So I’m happy to present for your reading enjoyment: Library Chicken’s Top-Ten(ish) Short Story Collections (So Far). (Please note that while I’d have no problem handing any of these to teenage or young adult readers — and many of them to upper elementary and middle school readers — some stories are definitely more adult-oriented and may contain sexual situations, violence, and/or racial or ethnic slurs. If you are considering short stories for your homeschool curriculum, please read them first so you can make the best choices for your own family.)

The Oxford Book of American Short Stories edited by Joyce Carol Oates

The Best American Short Stories of the Century edited by John Updike

100 Years of the Best American Short Stories edited by Lorrie Moore

These three hefty anthologies are great places to start if you’re looking to catch up on American short stories past and present. Many of the best-known and most-anthologized stories (and authors) in our literary tradition can be found here. Don’t be intimidated by massive size of these books — you should feel free to dip in and out and skip around.

The Serial Garden: The Complete Armitage Family Stories by Joan Aiken

ALL AGES. Sadly, I have not done as much reading (and rereading) of short stories for younger readers as I would like, but this collection is a standout. If I had discovered it a few years ago, it would have gone straight into our read-aloud pile; as it was, I immediately bought a copy for our home library. Every Monday (and occasionally on Tuesday) amazing and fantastical things happen to the Armitage family, and you owe it to yourself (and any children you may have wandering about) to get to know them better.

Growing Up Ethnic in America: Contemporary Fiction About Learning to be American edited by Maria Mazziotti Gillan and Jennifer Gillan

Amy Tan, Toni Morrison, Sandra Cisneros, E. L. Doctorow, Louise Erdrich — do I really need to say anything more? (This would be a fabulous text for a homeschool high school literature course.)

American Gothic Tales edited by Joyce Carol Oates

The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer

Short stories are traditionally the home of ghosts and ghoulies and things that go bump in the night, and these two anthologies have some of my favorite and most bizarre examples. They range from deliciously creepy to full-on horror, so read at your own risk!

Tenth of December by George Saunders

Get in Trouble by Kelly Link

What is Not Yours is Not Yours by Helen Oyeyemi

If you prefer your weirdness to come with a more literary bent, these three acclaimed authors can take care of that for you. (Also see any short story collections by Neil Gaiman or China Mieville.) If you have a middle/high schooler who claims to be bored with reading, definitely consider putting some of the stories collected here on your summer reading list.

...Which brings us to the end of our official Top Ten, but I can’t leave without recommending the following classics to all readers and especially homeschoolers:

pretty much anything and everything by Edgar Allan Poe

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle

The World of Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse

The Annotated H.P. Lovecraft by H.P. Lovecraft

The Lottery and Other Stories by Shirley Jackson

The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury

...and a personal favorite that I DID make all of my children read (because I’m a science fiction nerd):

I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

BONUS: Below is the list of stories that we read in our junior high literature class this past session. We typically read and discussed two stories a week. If you are considering coming up with your own list for summer (or whenever) reading, you could go with one story a week and still get a lot of great reading done. Also, when making up your own list, my advice is to start where I started: with the short stories that you love from your own reading AND with the ones (whether you loved or hated them) that still stick in your head from your own school days. If they made a big enough impression that you still remember them (ahem: see “To Build a Fire” below), there’s probably something there worth revisiting.

1. “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe

2. “The Adventure of the Speckled Band” by Arthur Conan Doyle

3. “Big Two-Hearted River” by Ernest Hemingway

4. “The Monkey’s Paw” by W.W. Jacobs

5. “The Luck of Roaring Camp” by Bret Harte

6. “The Courting of Sister Wisby” by Sarah Orne Jewett

7. “The Fall of the House of Usher” by Edgar Allan Poe

8. “To Build a Fire” by Jack London

9. “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Gilman

10. “A Worn Path” by Eudora Welty

11. “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” by Rudyard Kipling

12. “There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

13. “The Most Dangerous Game” by Richard Connell

14. “Quietus” by Charlie Russell

15. “It’s a Good Life” by Jerome Bixby

16. “Jeeves Takes Charge” by P.G. Wodehouse

17. “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” by James Thurber

18. “Good Country People” by Flannery O’Connor

19. “The Gift of the Magi” by O. Henry

20. “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” by Ambrose Bierce

21. “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut

22. “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” by Ursula Le Guin

23. “The Lady or the TIger?” by Frank Stockton

24. “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

(I didn’t read them in time for this session, but next time around I’d love to add “Everyday Use” by Alice Walker and “A Jury of Her Peers” by Susan Glaspell.)

Don’t Believe These Common Myths About Homeschooling High School

From getting into college to standardized tests, everything you think you know about homeschooling high school may be wrong — and that’s a very good thing.

Everything you think you know about homeschooling high school may be wrong— and that’s a very good thing.

Once upon a time, homeschoolers were more likely to turn to traditional schools when high school rolled around—fewer than 17 percent of the 210,000 homeschooled kids reported by the U.S. Department of Education in 2001 were high school students. There are lots of reasons parents may choose not to homeschool their teens through high school, but don't let false fear be one of them.

Myth: High school is too difficult for the average parent to teach.

Fact: You don’t have to teach everything.

In many ways, homeschooling high school can be much simpler than the early years because your teen is capable of independent study. Just be honest with yourself: What are you capable and willing to teach, and what do you need to outsource? Maybe you love the thought of digging deeper into history, but the prospect of teaching trig makes you want to break out in a cold sweat. Outsource subjects you don’t want to tackle—co-op classes, tutors, community college, online classes are all great options. As your student advances, your job will shift from teacher to educational coordinator—listening to him and guiding his class choices and extracurricular activities to prepare him for the college or whatever post-high school path he's interested in. It also means keeping track of classes for his transcript, staying on top of testing deadlines for standardized and achievement tests, and helping him start to hone in on the best people to ask for letters of recommendation.

Myth: Homeschoolers can’t take Advanced Placement (AP) tests.

Fact: Homeschoolers can take AP tests—whether they take official AP classes or not.

AP is a brand-name—like Kleenex or Band-Aid—which means the College Board gets to decide whether or not you can call your child’s course an AP class. (The College Board has a fairly straightforward process for getting your class syllabus approved on their website, and few homeschoolers run into problems getting their class approved.) You can build your own AP class using the materials and test examples on the College Board website and call the class “Honors” or “Advanced” on your transcript—and your child can take the AP test in that subject as long as you sign him up on time and pay the test fee. (Homeschoolers have to find a school administering the test willing to allow outside students, which may take some time. You’ll want to start calling well before the deadline.) If you’re nervous about teaching without an official syllabus, you can sign up for an online AP class or order an AP-approved curriculum. And remember: just because you take an AP class doesn’t mean you have to take the test.

Myth: It’s hard for homeschoolers to get into college.

Fact: Homeschooled kids may actually be more likely to go to college than their traditionally schooled peers.

This myth may have been true 20 years ago, but not anymore. Researchers at the Homeschool Legal Defense Association (HSLDA) found that 74 percent of homeschooled kids between age 18 and 24 had taken college classes, compared to just 46 percent of non-homeschoolers. In fact, many universities now include a section on their admission pages specifically addressing the admissions requirements for homeschooled students. In 1999, Stanford University accepted 27 percent of its homeschooled applicants—twice the rate for public and private school students admitted at the same time. Brown University representative Joyce Reed says homeschoolers are often a perfect fit at Brown because they know how to be self-directed learners, they are willing to take take risks, they are ready to tackle challenges, and they know how to persist when things get hard.

Myth: You need an accredited diploma to apply to college.

Fact: You need outside verification of ability to get into college.

Just a decade or so ago, many colleges didn’t know what to do with homeschoolers, and an accredited diploma helped normalize them. That’s not true anymore. (In fact, you may be interested to know that not all public high schools are accredited—only 77 percent of the high schools in Virginia, for example, have accreditation.) What you do want your child’s transcript to reflect is non-parent-provided proof of academic prowess. This can come in the form of graded co-op classes, dual enrollment courses at your local college, SAT or ACT scores, awards, etc. Most colleges are not going to consider whether your child’s high school transcript was accredited or not when deciding on admissions and financial aid.

Myth: A portfolio is superior to a transcript.

Fact: The Common App makes transcripts a more versatile choice.

Portfolios used to be the recommended way for homeschoolers to show off their outside-the-box education, but since more and more schools rely on the transcript-style Common Application, portfolios have become a hindrance. (Obviously, portfolios are still important for students studying art or creative writing, where work samples are routinely requested as part of the application process.) In some ways, this format is even easier to manage than a portfolio—you can record high school-level classes your student took before 9th grade and college courses he took during high school in convenient little boxes. And don’t worry that your student won’t be able to show what makes him special: The application essay remains one of the best places to stand out as an individual. Some schools even include fun questions to elicit personal responses: The University of North Carolina, for instance, asks students what they hope to find over the rainbow.

Myth: Homeschooled kids don’t test well.

Fact: On average, homeschoolers outperform their traditionally schooled peers on standardized tests.

All that emphasis on test prep in schools doesn’t seem to provide kids with a clear advantage come test time. Homeschooled students score 15 to 30 percentile points above the national average on standardized achievement tests regardless of their parents’ level of education or the amount of money parents spend on homeschooling. That includes college entrance exams like the SAT and ACT. Research compiled by the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics shows that homeschoolers scored an average 1083—67 points above the national average of 1016—on the SAT in 1999 and an average 22.6 (compared to the national average of 21.0) on the ACT in 1997. This doesn’t mean these tests aren’t important—good scores can open academic doors—but it does mean you may not have to worry about them as much you’d thought.

Myth: Homeschooled kids are not prepared for college.

Fact: Homeschooled kids adapt to college life better than their traditionally schooled peers.

This one always makes me laugh. Homeschooled kids probably have more hands-on life experience than their traditionally schooled counterparts. Homeschooled kids are usually more active in their communities, and because homeschooling is a family affair, they are more likely to have everyday life skills—the ones you need to make lunch for yourself or comparison shop for a tablet. Homeschooled teens also tend to be active participants in their own education, figuring out ways to manage their time and workload with their social lives long before they start college. Most importantly, they are able to interact and work with people of different ages, backgrounds, and cultures in a positive way, which is really the most important life skill of all. Perhaps that’s why homeschoolers are more likely to graduate from college (66.7 percent of homeschoolers graduate within four years of entering college, compared to 57.5 percent of public and private school students) and to graduate with a higher G.P.A. than their peers. Homeschoolers graduate with an average 3.46 G.P.A., compared to the average 3.16 senior G.P.A. for public and private school students, found St. Thomas University researcher Michael Cogan, who compared grades and graduation rates at doctoral universities between 2004 and 2009.

Who should we ask to write college recommendations for our homeschooler?

Recommendations give homeschool college applicants a chance to share what makes them special, so how do you find the right people to write recommendations for a teen who’s never been traditional school?

We’ve homeschooled all the way through school, and now my high school junior is getting ready to apply to college next fall — but because we’ve done almost all of our learning at home, there’s no obvious person to ask to write a recommendation for him. Should I just write his counselor recommendation and his teacher recommendation and explain that we are homeschoolers?

Congratulations! You must be so proud and excited for your son.

What colleges are looking for from a recommendation letter is deeper understanding of a student’s personality, ambitions, academic interests, successes, and challenges. Recommendations, along with your student’s transcripts, test scores, and application essay, give colleges an idea of what kind of personal and academic contributions your student will make to their institution.

The truth is that you’re probably the most qualified person to talk about these things for your son — but you should do that in your counselor letter, and ask someone else to write your son’s teacher recommendation. There’s a reason for this: If you’re putting together your son’s transcript, writing his counselor letter, and writing his teacher recommendation, colleges will only get one view of what your son is like as a student. Ideally, you’d want to offer them a variety of perspectives so that they get a more holistic view.

An obvious way to find someone to write a recommendation for your son is to sign him up for an outside class, preferably one that ties into his interests and abilities. I write lots of these letters for students who take my classes, and it’s always a pleasure — in fact, I assume that one of the reasons students are taking AP Literature or philosophy with me is because they want experience with an outside teacher, including a possible recommendation. But that’s not the only option: You can also ask troop leaders, teachers from art, music, or drama lessons, employers from internships or part-time jobs, volunteer directors and managers, or other adults who have a mentor-type relationship with your son. All of these people can speak to your son’s willingness to work hard and ability to work with other people, his time management and organization skills, his resourcefulness and talents — all information colleges look for in a recommendation later.

What if you’re really the only person who can write your son’s recommendation? Unless your son has stellar test scores (and even then), I’d really encourage you to consider at least a semester with an outside teacher so that you can add independent verification of his grades and abilities to his application — for homeschoolers, this kind of verification can be a big deal. (And really, it’s not a bad idea to let your son test the waters learning from someone other than you before he heads off to college anyway.) If you’re determined to write his recommendation, stick to the facts and try to give as many concrete examples as possible — don’t say “Allen is hard-working and responsible,” give a specific example of a time when he demonstrated hard work and responsibility. The more concrete examples you can give, the more your insight your letter can offer into your son’s abilities and ambitions.

Movies for Women’s History Month

Celebrate Women’s History Month this March with a homeschool movie marathon.

March is Women’s History Month, and every year, it feels more than ever like a time to think about how far women have come in the modern world — and how far we still have to go. These films will inspire and engage as you explore women’s history.

One Woman, One Vote

Susan Sarandon narrates PBS’s American Experience documentary on women’s rights, a well-rounded and informa- tion-rich introduction to women’s suffrage in the United States. Bonus: This documentary does a really nice job of exploring the role of black women in the suffrage movement.

Iron Jawed Angels

Hillary Swank and Frances O’Connor star in this sometimes weirdly directed but ultimately very compelling story about the U.S. battle for women’s rights. There are some invented historical incidents, but the overall story is rooted in real events.

Nine to Five

Maybe an indictment of women’s treatment in the 1980s workforce shouldn’t be this hilarious, but sometimes laughter really is the best social commentary.

Not for Ourselves Alone

Ken Burns takes on the women’s movement with this documentary focused on the lives of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two of U.S. history’s best known fighters for women’s rights.

The Magdalene Sisters

This film about the Irish institutions where“wayward women” were sent — and often abused — definitely deserves its R rating, so you may want to preview it. But since the last of these institutions didn’t close until the 1990s, it’s a movie worth watching with your older students.

The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter

The women who — more than capably — took on “men’s work” during World War II are the subject and stars of this poignant, powerful documentary.

A Midwife’s Tale

This fascinating documentary explores the life of an 18th century Maine midwife and the 20th century historian who discovered her diary and brought it to light.

14 Women

This sometimes overly earnest but still engaging 2007 documentary focuses on the — wait for it — fourteen female Senators in the 109th United States Congress.

Heaven Will Protect the Working Girl: Immigrant Women in the Turn-of-the-Century City

Before women won the right to vote, immigrant women crusaded for safer and more reasonable work conditions in booming factories and sweatshops. This short documentary illuminates their struggle — and victories.

The Burning Times

Some feminist scholars call the persecution of witches that occurred from the 1400s to the 1700s the “Women’s Holocaust” because of the huge number of women who were executed during this time. This documentary considers the history, causes, and effects of this problematic period in women’s history.

Thinking Beyond the 5-Paragraph Essay

Essays can be a good evaluation tool if you’re homeschooling high school but if you get stuck in a read-this-and-write-an-essay rut with your high school homeschooler, try one of these strategies with your high school homeschooler.

Essays can be a good evaluation tool in high school, but if you get stuck in a read-this-and-write-an-essay rut with your high school homeschooler, try one of these strategies with your high school homeschooler.

One challenge homeschoolers run into is how to evaluate your student’s learning — how can you help your student master the art of synthesizing information and expressing her own ideas about it? An essay is the classic approach — and it’s certainly a useful one — but essays can get boring if they’re your go-to for every single class. Here are some alternative evaluation projects to try.

Graphic Novel Adaptation

Transform the information into a graphic novel made of comic strip-style segments. This is ideal when you want to check understanding — do you understand what happened and the order it happened in? — so it can be handy for history or science evaluations. I also like using this method with poetry since thinking about how to illustrate a poem in a series of panels pushes you to think about it in a more nuanced way. This strategy works best when you’re dealing with a narrow, focused topic — trying to illustrate, say, Robinson Crusoe, would be a bigger project than you usually want.

Timeline

Another good option for corralling lots of factual information is the timeline, which can get more sophisticated as students move into higher learning. History timelines are common, but you can also use a timeline to track a novel where the timeline is significant (over years, like One Hundred Years of Solitude, or hours, like Mrs. Dalloway) or to explain a scientific process or concept.

Walking Tour

I love this idea for books where geography matters, like The Odyssey or Ulysses. This project encourages you to think about the significance of place in a very specific way, so it works best if you really push students to work to explain the significance of each place in their walk- ing tour. Instead of thinking about what happens in each place, think about why it matters and what the specifics of that place bring to the theme.

Metaphor Map

These are one of my favorite ways to explore complex ideas, like the categorical imperative, or complex texts, like modern poetry. Student have to really drill down to unify complicated information into one clear metaphor — essentially, coming up with their own creative explanation of a complicated text. The final illustrated metaphor, done well, is often more academically sophisticated than any essay could be.

Annotated Reading Notes

If your goal is to explore a wide range of texts, making comparisons and connections as you go, an annotated reading journal can accomplish that with more nuance and specificity than an essay. The key to doing this successfully is to model a set of annotations for students — if you’ve never done annotations, having a base to work from can be helpful. This is handy in classes like science and history where you’re covering lots of information you want to remember, but you don’t love the idea of giving lots of tests.

Podcast Series

Almost all the skills you need to write a great research essay — researching a topic, developing a thesis, and creating a structured argument around your thesis — come up when you’re creating a podcast. Aim for multiple episodes; ideally, you’ll ask for at least three so that students have a chance to do a proper introduction to the topic and a clear conclusion, but you can pick any number that seems appropriate.

Oral Defense

This one can be stressful for students the first time, but you may be surprised by how enthusiastic they become with a little experience. Basically, you treat your evaluation like a classic dissertation defense: Students prepare to face a panel of advisers (you can include friends, siblings, or just go it solo), and in a directed conversation explain their understanding of a topic, making connections and thinking on their feet to answer the questions posed them.

How do I put together a high school transcript for an unschooled student?

The key is to figure out how all the learning you've been doing unschooling through high school fits into the framework your dream college is looking for. Because it does.

Lisa asked: My always-unschooled 17-year-old has always been adamant that college isn’t on is to-do list — but now, just as he’s getting ready to start what’s technically his senior year this fall, he’s fallen in love with a fairly traditional college (with a reputation for being tough on homeschooled applicants) and made up his mind that’s what he wants to do next. I want to support him, but I have no idea how to pull together a high school transcript (which his dream college does require) when we’ve done very little formal schoolwork for high school. Can you help?

Obviously your life right now would be a little easier if you’d been keeping careful records for your son’s high school transcript since eighth grade, but honestly, it’s no big deal that you’re just starting to think about it at the end of junior year. (I’m not sure if it’s exactly comforting, but there’s a not-small percentage of homeschool parents who don’t start thinking about transcripts until their student’s senior year is ending — and many of them do just fine pulling them together even at that very last minute.) Putting together this transcript is totally doable.

Start with a simple transcript template like this one so that all you have to do is fill in the blanks. (Transcripts for very traditional colleges are one place where creativity doesn’t really pay off — you’ll usually fare best if your transcript looks like everybody else’s.) Now look at the college your son has his sights set on: What core academic classes does it require for incoming freshman? Often, the requirements look something like this: 4 units of English, 2 units of algebra, 1 unit of geometry, 1 unit of trigonometry, calculus, statistics, or other advanced math, 1 unit of biology, 1 unit of chemistry or physics, 1 unit of additional science, 1 unit of U.S. history, 1 unit of European history, world history, or world geography, 2 units of the same foreign language, and 1 unit of visual or performing arts.

Now a list like this might initially make you feel kind of panic-y because it seems like the most structured thing ever and your problem is that you’ve got almost no structured stuff to draw on, right? In fact, though, a list like this is a great thing for homeschoolers because it helps you focus in and figure out how all the learning your son has been doing might fit into a more traditional framework. Just because he hasn’t been checking off boxes for the past three years doesn’t mean he hasn’t been learning — which you know, of course, but which can be easy to forget in the face of a form full of those boxes. For instance, all that time he spent hatching tadpoles, creating microscope slides, growing carnivorous plants, dissecting owl pellets, and volunteering at the zoo? That might add up to Biology. Or the year he spent reading every Philip Dick book and comparing the books to movie interpretations of them? That’s comparative literature in action and can count as a semester of English. What about math? Frankly, if you haven’t done organized classes, the simplest thing to do may be to just to ask your son to take a few placement tests to see what math he’s mastered — then you can list the maths he’s mastered on his transcript. As you realize how much your son has actually accomplished over the past three years, his transcript will fill in pretty quickly — and you may be tempted to get whimsical with course names and descriptions, but if the school he’s aiming for really is super-traditional, it really is best to just keep it as simple as you can: Biology, rather than Exploring the Natural World, or Literature: Science Fiction instead of The Worlds of Philip Dick. Yes, coloring inside the lines is a little boring, but you’ve happily lived outside the lines (and can continue to do so). This is just a hoop that you’ll jump through more easily if you present your out-of-box experiences in a form that fits neatly into the admission committee’s boxes. (Plenty of colleges are receptive to homeschool resumes and appreciate the kinds of interest-driven classes that homeschoolers have the opportunity to take. You just want to know what the school you are applying to is looking for.)

After all this list-making, you may have some holes — but you’ve got his entire senior year to fill them. Don’t worry if you have multiple classes to fill in — maybe you need to cover geometry and trigonometry or take two English classes. This is pretty easy to manage with a little strategic planning. Sit down with your son, and come up with a game plan for what to do over the next year so that his transcript matches up with the requirements for his dream school. (If you need to, you can set your graduation date for the end of summer instead of spring to get a little more time. Remember, you’re the one who has the power to determine your academic year.)

You don’t mention whether you’ve been doing any outside classes, but if you haven’t, make sure to enroll in a couple this fall. They’ll make your transcript a little easier, yes, but they’ll also connect you to other teachers who can help describe your son’s achievements and college suitability when the time comes to start soliciting teacher recommendations for your application. You can handle the transcript thing on your own, but you will definitely benefit from having outside, unbiased teachers for your son’s teacher recommendations.

Good luck! It can feel intimidating to tackle this on your own, but just like every other part of homeschooling, taking it one step at a time and keeping your student top of mind will get you through.

Alternatives to To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird is worth reading — but don’t make it the only book about racial justice on your list, or you’re missing the point.

Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird is worth reading — but don’t make it the only book about racial justice on your list, or you’re missing the point.

It’s not that Harper Lee’s coming-of-age classic isn’t a good book — it is. The problem comes when we try to make it the great American novel about racial justice — which it’s not. How could it be when it’s focused on racism as an incident in the coming-of-age story of a white woman and when its hero is a white man who never actually comes out and condemns racism? So read To Kill a Mockingbird — please read all the banned books! — but also read these books that shift perspective from a young white girl to actual experiences of people of color.

The Hate U Give BY ANGIE THOMAS

If Scout were a young Black woman and Tom Robinson was her friend, you’d get close to the vibe of this YA novel. Starr Carter lives in a poor Black neighborhood and attends a ritzy white private school, putting her smack in the middle of two worlds. Those worlds collide when her best friend is killed in a police shooting during a routine traffic stop — while Starr is sitting in the passenger seat. Like Mockingbird, The Hate U Give looks at the ways racism affects institutions we trust — like the courts or the police.

All American Boys BY JASON REYNOLDS AND BRENDAN KIELY

Quinn didn’t see what happened in the store, but he did see the aftermath: His friend’s police offer brother relentlessly beating Rashad. Told in Quinn and Rashad’s alternating perspectives as they navigate the aftermath of Rashad’s beating, this is a hard book to read in light of everything that’s happening in the world right now. That’s exactly why you should read it.

Dear Martin BY NIC STONE

Justyce is used to living in a world where the fact that he’s a young Black man is enough to make the people around him fear and suspect him — but that doesn’t mean he likes it. He finds solace writing letters to his hero Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who made great strides for Black civil rights — but who also ended up dead because of racism. (The sequel, Dear Justyce — about two friends who grow up together in Atlanta before their paths diverge — one to Yale University, one to the Fulton Regional Youth Detention Center — is also a contender.)

Internment BY SAMIRA AHMED

Mockingbird was set in the past, but Internment imagines the future: In a not-too-distant United States, Muslim-Americans are forcibly relocated to internment camps. Teenage Layla is one of them, and she’s more than ready to join the brewing rebellion. Though Internment has some literary flaws (including an unfocused second act and spotty character development), its premise is enough to make it worth reading. When is it OK to decide someone’s existence makes her a threat to society?

The Round House BY LOUISE ERDRICH