Working Full-Time and Homeschooling: How I Do It

I’m totally lucky to get to balance a job I love with hands-on homeschooling, which I also love, but hitting that balance isn’t always easy, and I’m learning to be okay with that.

I’m totally lucky to get to balance a job I love with hands-on homeschooling, which I also love, but hitting that balance isn’t always easy, and I’m learning to be okay with that.

I work full-time. (And then some.) I also homeschool my kids in a pretty hands-on way. And you might think that this all gets easier as kids get older and more independent, but I’ve found the opposite to be true. High school homeschooling, when you’re doing most of it in the homeschooling-at-home kind of way, takes a lot of time and energy. People are often interested in how I balance these two big jobs, so I thought I’d write a post about my work/homeschool balancing act.

First off, I’m pretty sure a lot of the time that I do it pretty badly. It’s not easy. Things slip through the cracks. I have a vague, nagging sense of guilt all the time, like whatever I’m doing at any given time, I should be doing something else. (I’m not saying this to complain — I know I’m lucky to get to do things this way. But I think it would be totally fake to pretend that working full time and homeschooling is easy or that I do it well all the time!)

And second, I love what I do. I think I have the best job in the entire world, and I find homeschooling really fun and satisfying. I think if either one of those things weren’t true, my situation would feel much harder. I also know that I’m able to make my balancing act work because when my kids were younger, I worked 95% of the time from my home office. That changed when my oldest started high school and I started a hybrid homeschool in Atlanta; first I worked one day a week teaching AP English, then two days a week running the high school humanities program, and now I’m at the school five days a week for middle and high school. My youngest, who is in 11th grade, is a student at the school, though we also do a lot of homeschool stuff together at home.

Here’s what works for me:

I completely let go of the idea of a normal workday.

I have a big workload, and in a more traditional environment, I’d be logging plenty of overtime. Last year, I made the decision not to keep up with my hours of work time at home or try to set up a consistent schedule. I work when I need to work. My kids are late sleepers, so I’m usually able to get in three or four hours of work before they wake up in the morning. I usually work while I eat lunch and then in the afternoon and evening when the kids are doing their own things. I work through the weekend. Most days, we’re actively homeschooling for about four hours, and we try to spend at least an hour or two every day just doing something fun together — watching a show, playing a game, taking a walk, tackling a new craft project, whatever. I have accepted the fact that I’ll be working a lot every day, including weekends and holidays, and I try to make my non-work hours really count.

I do not try to do everything.

I usually make dinner and we all eat together, but unless I’m at home and feeling particularly into it, I don’t do breakfast and lunch — everyone’s on their own for that. (I stock up on easy-to-make things like instant oatmeal, sandwich fixings, or yogurt, and do occasional mega-cooking sessions where I freeze individual portions of meals like macaroni and cheese or enchiladas that the kids can heat up. Sometimes I buy frozen meals from the supermarket. I try to buy the healthiest ones, but I buy them, and I don’t feel guilty about it.) Our house is usually messy because cleaning is low on my priority list, and I’m okay about that. (Well, at least mostly!)

I push myself to be all-in with whatever I’m doing.

When your to-do list never ends, it’s easy to feel perpetually fragmented — you’re doing one thing, but your mind is on something else. I work hard to stay in the moment: If we’re homeschooling, I turn off my phone. (I’ve actually got my phone set up so that it doesn’t even receive work email — I have to check it on my desktop.) If I’m writing a lecture, I don’t check Facebook until the lecture is done. Some multitasking is inevitable and some days I do better at staying in the moment than others, but I really try to stay focused on one thing at a time.

I compartmentalize.

Along the same lines, I keep a separate bullet journal for life (including homeschooling) and for work. This makes sense practically because my work timelines and my life schedule are pretty different, but it’s also symbolic: When I open my work bullet journal, I’m working. When I close it, I turn off work—as much as I can, anyway, when my office is just steps away from my bedroom. This is a small thing, but it’s made a big difference for me: Now, I have a life calendar that doesn’t just get swallowed up by work to-do lists.

I say no to extra stuff.

I wish I had time to go to every homeschool day and park day and play date, but that’s just not realistic with everything else I have to do. So the kids and I try to choose one out-of-the-house adventure each week, and that’s it. I don’t take on volunteer projects, even when they’re awesome projects that I really believe in, or extra responsibilities, even when they come in the form of super-fun classes I could teach. I have to know my limits and be honest with myself about them.

I take time for myself.

Our house would certainly be much tidier if I went straight to housecleaning every time I logged off from work — but that’s never going to happen. Carving out little corners of free time for myself is really important to me. So yes, I could be cleaning when I’m watching Poldark with Jason or having lunch with my best friend or knitting on the back deck, but I would feel overwhelmed very, very quickly. I don’t always get a lot of me-time, but when I do, I never feel guilty about using it for what I want to do (not what I might think I need to do).

I try not to talk about how busy I am.

I know people whose conversations always seem to circle back around to how busy they are, and I don’t want “busy” to become the way people think of me — or, more importantly, the way I think of myself. So yeah, I’m busy, but unless you catch me right on the cusp of a magazine deadline, I’m not going to tell you all about it. I’m going to enjoy the break that I get chatting with you for all its worth and go back to my projects a little rejuvenated when the conversation is over. Dwelling on how busy I am just makes me feel busier, if that makes sense.

I take busy work weeks off from homeschool — and vice versa.

When we’re ramping up for a new term at the Academy or I’m on a big deadline for a project, I don’t even try to do any kind of structured homeschool — our homeschool has a year-round calendar, so a week off several times a year isn’t a big deal. Similarly, if we have a big homeschool project going — like the trip we took to Savannah this year or our big New England road trip over last spring break —I organize as much as I can in advance so that I can do the bare minimum work stuff during that time. I’ve learned that when something needs my full attention, trying to split my attention is a recipe for stress and grouchiness.

I feel like this balancing act is always a work in progress — for every day that I finish triumphantly, feeling like I’m that one person in a million who’s figured out how to have it all, there’s a day where I feel like the worst mom/wife/editor/teacher/friend in the history of the world. Mostly, though, I’m thankful that I get to have a job that I love, homeschool my kids, and make it — mostly — work.

Sometimes Homeschooling Is Right for One Kid in Your Family and School Is Right for Another One — And Good Homeschooling Is Supporting That

When traditional school is right for one kid and homeschooling works best for another, back-to-school season can look really different. There’s plenty of room for all the options in a happy homeschool life, Carrie discovered.

When I first started homeschooling, I’m pretty sure I believed that homeschooling was all-or-nothing: either you homeschooled your kids throughout their childhoods, or you sent them off to school. But many families I know aren’t like that. Maybe their kids homeschool for most of their childhoods, then head to junior high or high school. Maybe their kids avail themselves of select activities at schools but remain homeschoolers. Maybe some of a family’s kids attend school, while others homeschool.

We’re that kind of family — a part homeschooling, part schooling family. Our 13-year-old son learns at home and has no interest in going to school — ever. Our 10-year-old daughter attends a private, part-time “school for homeschoolers” and says she never wants to go back to full-time homeschooling. It’s a combination that works surprisingly well for our family. You’d never know just how much hand-wringing and agonizing it took to get us to this point.

Our part-time schooling arrangement came about during a particularly long, brutal winter up here in Minnesota in 2013-2014. Cooped up by heavy snow and wind chills that were regularly hitting 20 or 30 below zero, the only learning we seemed to be doing was about working through interpersonal conflict, and boy, was there a lot of that kind of learning. I was stressed. They were stressed. My energy for homeschooling was at an all-time low.

One bitter-cold February day, I sat both kids down in the living room and said I thought we needed to really look at whether homeschooling the way we were was the happiest choice for our family. My daughter, then eight, burst into tears.

“But I don’t want to go to school!” she wailed.

I told her there might be another, less drastic option. A few old homeschooling friends of ours had ended up attending a three-day-a-week Christian Montessori school intended to give homeschoolers some of the benefits of school while allowing time for family learning, too. The school had unusually long breaks — six weeks off in December and January, two weeks in March — and finished for the year in mid-May. There were no grades, no tests, and minimal homework. It felt like School Lite — a gentle way to try out school without completely giving up on homeschooling.

My son was emphatically not interested. My daughter agreed to check it out.

The day we toured the school, I was impressed by the school’s peaceful, friendly atmosphere. But there were also things that gave me pause. The school was run by evangelical Christians, but our family isn’t Christian. Would my daughter be accepted here? Could we as a family feel comfortable here even though we don’t go to church and aren’t believers?

My daughter was quietly observant throughout the school tour, her body language stiff. By the end of the tour, I was sure she was going to say she wasn’t interested. Honestly, I kind of wanted her to say she wasn’t interested. As miserable I’d been with homeschooling that winter, I didn’t feel ready to give it up, either.

As we left the school and walked to our car, I asked my daughter, “So, what did you think?”

“I liked it!” she declared. She was perfectly clear on the matter; she was going to that school that fall.

I wept many tears that spring and summer, agonizing that sending her to school was a big mistake (always out of sight of my daughter, of course).

My daughter did occasionally feel out-of-place attending a school where almost all the other kids were regular churchgoers. She was startled when one teacher mentioned that they didn’t teach about evolution at her school, but that they prayed for people who believed in it. My daughter had taken a class about evolution at our local zoo the year before and had read extensively about it at home. The idea that her school would completely dismiss discussing it floored her.

At home, we talked about approaching these sorts of differences as a chance to learn about the range of perspectives that make up our country and our world and the different ways people approach controversy and disagreement. We brainstormed how she could stay true to herself even if she didn’t feel comfortable speaking up loudly at school. I was grateful that our family’s work together as homeschoolers had laid down a foundation for us to talk this way, and that my daughter’s years as a life learner have given her a strong sense of self she can fall back on when she feels confused or out-of-step with the people around her.

As that first year went on, my daughter found that she really liked the way Montessori learning combines structure with freedom of movement and choice. She’s also fairly introverted, and she found that her school — a school where “nobody knows how to be mean,” as she put it recently — helped her come out of her shell. Seeing the same kids regularly in a routine, predictable environment was more comfortable for her than going to unstructured homeschool play groups, where she’d mostly clung to my side and not talked to the other kids. Once-a-week, short-term classes for homeschoolers also hadn’t really given her enough time to warm up to other kids.

I still don’t believe that school is necessary for kids to get “socialized” — it’s simply that for my individual kid at the developmental stage she was at, this particular school was a better social fit.

Meanwhile, back at home, my son was enjoying having three days a week of one-on-one time with me, combining a few classes at a local homeschooling co-op, a bit of math, lots of reading, and plenty of time pursuing his passionate interest in all things gaming-related. Some days, it felt like we had our own little writer’s colony of two, as my son worked in one room on video game-inspired fan fiction or creating the rules, characters, and storyline for a role-playing game he was designing, and I worked in another room on my own writing. We’d check in with each other over lunch, a board game, or during a hike by the Mississippi, two creative colleagues egging each other on.

My daughter is now preparing for her third year at her school. It will probably be her last one there; she’s feeling ready for a secular learning environment, where she doesn’t worry that she might scandalize a schoolmate if she mentions a pop singer she likes or alienate a teacher if she mentions evolution in a school project.

Luckily for us, there’s another part-time option for schooling here in our town, a public charter school where students attend classes in person three days a week and then work at home two days a week. She is hoping to transfer there for sixth grade. She wants school, yes, but she still wants a bit of freedom about how she spends her days, too.

I tell her that if she’d ever like to return to homeschooling, it’s always an option. She just smiles. “You really want me to come back to homeschooling, don’t you?” she teases me.

Well, yes, I’d love for her to come back to homeschooling. But what I want even more is for her to know she has choices. I’ve learned I can trust her to make the best of whatever situation she’s in and to know what’s right for her, even if it’s not what I would have chosen for her. She’s learned that she can handle new experiences with grace, take the good with the bad, and then walk away when something is no longer working for her. Those are lessons that I think will serve us both well as she moves forward in her life’s adventures, wherever they take her.

Great Books for Your Secular High School Detective Fiction Unit Study

Studying literature is a lot like being a detective — you’re looking for clues, hints, and details that reveal a bigger story. That’s why a high school detective fiction unit can be a great addition to your homeschool plan — and, bonus, reading detective stories is also a lot of fun. These are some of Suzanne’s favorites.

From Sherlock to chemistry prodigies and everything in between, classic detective fiction is sometimes just the comfort read you need. These are some of our favorites.

It all started with Nancy Drew, of course. Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, Encyclopedia Brown, the westing game, Trixie Belden, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Three Investigators. So it was natural that sometime around junior high, having exhausted my local library’s children’s section, I gravitated toward the mystery section over on the adult side and discovered Agatha Christie. (It wasn’t a very big section, as I recall, and after a year or two I’d finished off everything that looked promising and moved over to the neighboring science fiction/fantasy shelf. Once I discovered sf I took a several-decades-long break from the mystery genre — with the exception of Isaac Asimov’s mashup robot mystery series that begins with The Caves of Steel — but that’s a different column.)

When people ask me about young readers moving to “grown-up” books, I think of Agatha Christie first. Not only is she Queen of Mystery Writers, she was wildly prolific, and there’s nothing I loved more at that age than finding an author and realizing I had dozens and dozens of books to look forward to. That’s still true today, of course, and it’s one reason I’ve recently found my way back to the mystery section. When everyday life makes me a bit crazy, and I don’t have emotional energy to tackle the big thick novels on my to-read list, it’s comforting to pick up a favorite mystery writer — or find a new favorite — and know I’ve got shelves and shelves of books waiting, where I get to hang out with the sleuths I’ve come to love.

So what do you do after you’ve read your way through Poirot, Miss Marple, and Tommy and Tuppence? First, you reward yourself by watching the Agatha Christie episode of Doctor Who (“The Unicorn and the Wasp”), and then you go back to the beginning with Sherlock. We started the Sherlock Holmes stories as readalouds with my two oldest children (then upper elementary and middle school) shortly after the entire family became obsessed with the BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch. It was great timing: having met the characters on television, my kids had a lot more patience with the Victorian literary stylings (and sometimes ridiculous plots), plus we were able to pick up all the references to the original works sprinkled throughout the show. And, of course, one of the great things about Sherlock is that he’s been adapted and adopted so many times that you can keep reading him forever. My first experience with professional fanfic (long before the term “fanfic” was invented) was Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Percent Solution (Holmes meets Sigmund Freud) and The West End Horror (Holmes meets everyone else, including G.B. Shaw, Bram Stoker, and Oliver Wilde). I’ve read several of the Mary Russell/Sherlock Holmes mysteries by Laurie King (beginning with The Beekeeper’s Apprentice) and enjoyed Michael Chabon’s Sherlock novella, The Final Solution. My very favorite borrowing of the great detective may be Lyndsay Faye’s Dust and Shadow: An Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr. John H. Watson, though she has tough competition from Eve Titus’s children’s series Basil of Baker Street (hurray! the inspiration for Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective is finally back in print!). But the books keep coming: I’ve got The House of Silk, a Sherlock story by Anthony Horowitz (author of the wonderful Magpie Murders, a murder mystery about the publication of an Agatha Christie-type murder mystery) in my bedside to-read stack right now.

As a younger reader I somehow managed to miss out on Dorothy Sayers’s mysteries, but once I finally discovered Lord Peter Wimsey, gentleman detective, I couldn’t get enough of him and his complicated romance with Harriet Vane. Sayers’s books are not necessarily easy or simple, but she’s been on my ‘comfort read’ shelf (next to Agatha Christie and Georgette Heyer) for years.

Many readers encounter Josephine Tey’s detective, Inspector Alan Grant, in The Daughter of Time, a historical murder mystery (where Grant, laid up in the hospital, tries to solve the murder of the Princes in the Tower) that keeps showing up in ‘best mysteries of all time’ lists. Recently I read all of the Alan Grant books (which make good use of Tey’s real-life experience in the theater world) and found out what I had been missing. Tey writes good, solid mysteries that are a little bit quirky and often take a different and unexpected path from other Golden Age detective stories. But the strangest detective series I’ve read (and am still in the process of reading) has to be Peter Dickinson’s Inspector James Pibble books. So far, Pibble has encountered a lost tribe from New Guinea, man-eating lions, psychic children, and two different island monasteries inhabited by crazed monks. I have no idea what to expect in the sixth and final book in the series.

Pibble, whose books were published in the 60s and 70s, comes a bit after the British Golden Age of crime fiction, but as an English inspector he fits right in with that tradition. I could read and reread those authors forever, but I’m grateful that there are slightly more diverse options available. One of my favorite ongoing series (and a great one to hand middle and high school readers, though it’s marketed for grown-ups) is by Alan Bradley and stars Flavia de Luce, an 11-year-old science prodigy living in a broken-down country estate with her slightly bizarre family in 1950s England. We’re introduced to Flavia when she solves her first murder in The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie. (These books are worth reading just for the titles.) Another book I’ve handed to middle school and YA readers is Alexander McCall Smith’s The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, the first in the long-running (and still going strong!) series set in Botswana and starring the independent and strong-minded Precious Ramotswe.

I’m running out of space and I haven’t even gotten to Dalziel and Pascoe (a hard-boiled crime series — beginning in 1970 with Reginald Hill’s A Clubbable Woman — that expands over the years to include both a Jane Austen homage and a trip to space), Amelia Peabody (amateur Victorian Egyptologist crime-solving!), or Phryne Fisher (a 1920s Australian sleuth who is very much NOT for young readers—but grown-ups need books too). I’ve also neglected to mention some of my favorite stand-alone mysteries, including Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (where the murder victim is a dog and our narrator-sleuth is a teenage autistic boy), John Dickson Carr’s The Murder of Sir Edmund Godfrey (a nonfiction account of the murder of a judge during the reign of Charles II that reads like a modern mystery), and Hazel Holt’s My Dear Charlotte (an epistolary mystery inspired by Jane Austen’s letters).

Moving to the Passenger Seat — Literally and Metaphorically — as Our Homeschooled Kids Grow Up

Learning together has become our family culture, and I imagine our shared education will extend far beyond their graduation. I look forward to the lessons they have in store for me. There’s so much to see from the passenger seat.

Homeschooling may not look exactly the same as our kids get older, but we’re all still homeschoolers at heart.

We circled the parking lot several times before settling for a parking spot a block away from the library. So many station wagons and minivans signaled that today was preschool story time. It had been years since I loaded my preschool aged children into our Volvo wagon to make our weekly trek to the library, where we’d sit on carpet mats on the floor of the community room to hear our favorite librarians read out loud.

“It seems like just yesterday that we were going to story time, and now you’re driving me to the library,” I said to my daughter as she parked my Subaru.

Times change, cars change, roles change. And just like people tell you when your kids are young, it happens so fast. My little girl is now taller than I am. She has her driver’s permit and has claimed her own set of keys to my car. In a few weeks, she will be done with high school, two years ahead of schedule. In a few months, she will get her driver’s license and begin taking classes at the local community college. If all goes according to her plans, she will also get a job. These are the events she’s been preparing for the last ten years of homeschooling, but it’s hard to believe they’re scheduled on this year’s calendar.

Even though I have one child on her way to college, and another child who has opted to attend a traditional middle school after homeschooling throughout the elementary grades, I am a homeschooler at heart. Some things don’t change. As my kids have grown and chosen their educational paths, our classroom has expanded beyond math at the dining room table, science at the kitchen island, PE at the park, literature via audiobooks in the car, and field trips to historical monuments. Learning together has become our family culture, and I imagine our shared education will extend far beyond their graduation. I look forward to the lessons they have in store for me. There’s so much to see from the passenger seat.

How to NOT Teach Your Kids Shakespeare (But Do Something Else Really Important Instead)

Instead of trying to be an authority who has all the answers, I get to learn with my kids and be surprised alongside them. In the process, I get to show my kids what learning looks like, in all its messy glory.

This spring a fellow homeschooling mom I know mentioned a book she was planning to use with her family, Ken Ludwig’s How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare. Ludwig, an award-winning playwright and Shakespeare aficionado, believes that the best way to truly appreciate Shakespeare is to memorize passages from his plays and poetry, so he’s selected a wide range of kid-friendly Shakespeare passages and laid out a step-by-step method for breaking the passages into manageable bits.

As a literature geek, I was immediately salivating at the thought of sharing Shakespeare this way with my son, who’s 13, and my daughter, 10. I knew it might be a stretch for us: my kids tend to be stubborn autodidacts who resist any activity that casts me in a “teacherish” role. But they’ve also enjoyed seeing outdoor Shakespeare performances in our local parks since they were little. I figured they might surprise me and agree that memorizing some Shakespeare together was just the thing our summer needed.

I broached the subject with the kids, pitching it as a way to get in the mood for the Shakespeare performances we’re planning to see this summer. They said “Uh, sure, I guess” in the lukewarm, shifty-eyed way they say yes when they don’t want to rain on my parade but are clearly hoping I’ll forget the whole thing.

Still convinced that they’d get sold on the project once we started rocking our mad Shakespeare skills, I set aside some Shakespeare time on our calendar. Week after week, something always got in the way of us taking a crack at Shakespeare. It was time to face facts: My kids really didn’t want to memorize Shakespeare with me.

I like to make the most efficient use of my mama-energy, and what I’ve found is that I just don’t get a very good return on my effort when I push a project that neither kid is enthusiastic about. On the other hand, I’ve seen many times how powerful the results can be when I back off on my agenda and follow the kids’ interests instead. The learning is deeper and longer-lasting. There’s a flow and an energy that just isn’t there when I force things.

So I put aside my Shakespeare dreams, at least for now, and asked myself the million-dollar question: what had my kids actually been saying they wanted to do this summer? That’s when it struck me: the big thing that my daughter had been saying for months is that she wanted to redecorate her room.

This is a girl who loves design, who constructs dream houses for make-believe clients on Minecraft and revels in mid-century modern consignment stores, a girl who adores thinking about colors and patterns and how they interact. The thought of tackling a room redecorating project intimidated me, but I knew that following through on helping my girl create a new space for herself would mean a lot to her.

Exit, stage right: Shakespeare memorizing scheme. Enter, stage left: room redo.

Together, my daughter and I set a budget for our project. We slapped paint samples on her wall and changed our minds about a half-dozen times (we finally decided on Turquoise Twist, a gorgeous shade reminiscent of a robin’s egg). We checked out online painting tutorials and conferred with the friendly folks at our neighborhood hardware store. We applied painter’s tape to baseboards and wooden trim, sanded rough spots, scraped off remnants of stickers and Scotch tape. We calculated how much paint she’d need to get the job done. And finally — deep breath — we started painting.

Neither of us had ever painted a room before. After swiping a paint roller across her wall for the first time, my daughter frowned and said, “Maybe we should hire someone to do the painting for us. I’m afraid it won’t look good if we do it ourselves.”

I couldn’t help wondering if she might be right, but I assured her that if we followed the painting pointers we’d studied and took our time, we could do a fine job. Maybe not as good as a professional, but good enough. I didn’t want her to miss out on the delicious feeling of competence that comes from trying something you want to do but fear you might not be able to do. (I also wanted to keep her project under-budget.) On this point, unlike memorizing Shakespeare, I was willing to push a little.

We finished the painting a few days ago. It’s not perfect, but the overall effect makes my daughter really, really happy. I think the room means more to her because she was so involved in making it look the way it does. It’s her ideas and work, made tangible.

We’ve spent the last couple of days assembling a storage unit and a desk. There have been many times when we’ve realized we have a part oriented the wrong way and have to remove all our screws and start a step of the process over. We had to problem-solve with her dad when her desk drawers didn’t line up right.

Thinking about all the times that she saw me messing up and starting over during this project, it struck me today that one of the very coolest things about doing this kind of a project with my daughter is that she got to see me being a rank beginner. She watched me looking up answers when I needed them and asking for help when I hit dead ends. She saw how I paced myself to get the job done, taking breaks when I needed them, getting my hands dirty and doing the work alongside her to help turn her daydreams into reality.

In other words, I got to model being a learner right there in front of her eyes. For me, that opportunity to model lifelong learning is one of the most wonderful things about homeschooling. Instead of trying to be an authority who has all the answers, I get to learn with my kids and be surprised alongside them. In the process, I get to show my kids what learning looks like, in all its messy glory. That’s definitely a part of homeschooling I treasure—even if it means I often end up putting aside projects that sound really cool to me in favor of what most interests my kids.

Which brings me back to Shakespeare. If you and your family think Ken Ludwig’s Shakespeare book sounds fun and you decide to memorize some Shakespeare, could you please let me know? I’d love to hear how it goes and find out what you discover along the way!

We All Know Self Care Is Important—But Where Do You Find the Time?

Self-care is an essential part of the homeschool equation for secular homeschool moms, and you’re going to have to be deliberate about fitting it into your days.

Self-care is an essential part of the secular homeschool equation, but you’re going to have to be deliberate about fitting it into your days.

A decade ago, I began homeschooling my children for selfish reasons. Sure, I thought homeschooling would be good for them too, and I read a stack of books about childhood development, learning styles, and homeschooling methods to back up that belief, but ultimately my reasons to homeschool were selfish. I wanted my children to learn free of negative social influences, gold star grading systems, and hours of pointless homework, but mostly I didn’t want to wake up early every day to rouse my sleeping children, pack brown bag lunches, and hurry them out the door. Waking up naturally and snuggling on the couch to read books before we began our day of curiosity driven learning was my romanticized fantasy of homeschool life.

There were many days that we lived out my fantasy, but many more days that I lost myself in the service of parenting and homeschooling. When mothers with more experience than I had counseled me to take some “me time,” I didn’t even know what they meant. All the hours not devoted to the enrichment of my children were spent cleaning up from said enrichment, planning for the next day’s enrichment, and recovering from all the enrichment, plus the usual business of running a household. When exactly was this “me time” supposed to happen, and what was I supposed to be doing for myself?

I recently listened to an interview with a 107-year-woman, and when asked for the secret of her longevity her answer was to eat well, exercise, sleep, and avoid stress — four of my favorite things to do now, but not my priorities during those early years of homeschooling. Hearing it from a woman with a tremendous amount of life experience affirmed that taking care of myself is my definition of “me time,” and hopefully it will buy me even more time.

As the new school year approaches, and you thoughtfully select and prepare curriculum for your children, consider the enrichment of yourself as well. Schedule “me time” in your daily planner, and keep the lesson plan simple: eat well, exercise, sleep, and avoid stress.

Here are a few sample assignments:

Eat vegetables with your breakfast, because at the end of a long day when the idea of making a salad seems as monumental a task as teaching Latin to a preschooler, and you wonder if the marinara sauce on your pasta counts as a vegetable, at least it won’t be your only vegetable that day.

Station your kids on the front porch with a timer and have them record how long it takes you to walk (or run!) around the block multiple times. Find the mean, median, and mode of your times and call it a math lesson. Extra credit if they cheer you on.

Schedule a 20-minute power nap for that particularly stressful time of day when you begin to consider packing a lunch for your children and dropping them off at the nearest public school.

Replace a “should” with a “want”: I should (insert an activity that stresses you out), but I want to (insert an activity that feeds your sense of self). You can’t avoid all shoulds in life, but if you’re not careful you may successfully avoid all of your wants.

One of the greatest lessons I learned and passed on to my children is the importance of taking care of oneself. If you don’t make yourself a priority, who will? A bonus to this lesson is that others often benefit from your acts of selfishness. My selfish desire to homeschool was a selfless act of service to my children, and an inspiration for friends to choose alternative educational paths.

Families make great sacrifices of time, energy and resources in order to homeschool, but caring for yourself does not have to be part of that sacrifice. This school year, make “me time” a mandatory subject. What is good for you is also good for your children.

3 Summer Planning Tips for a Happy Homeschool Year

Nothing makes a secular homeschool year run more smoothly than spending some summer hours creating a specific plan for the following academic year.

Nothing makes a secular homeschool year run more smoothly than spending some summer hours creating a specific plan for the following academic year.

Who else looks forward to summer days spent lugging coolers and towels to the beach and spending hours refusing to move off your beach lounger for all but the most desperate of cries? Summer is meant to be enjoyed and during a good summer break, a house should be full of sand, dirt, and sunburned kids.

On my beach lounger, though, I begin to dream about our homeschool. I maintain that nothing makes a homeschool year run more smoothly than spending some summer hours creating a specific plan for the following academic year.

If you school year round, this post is for you, too. Use use whatever break you take for an annual review and planning what comes next.

STEP 1: The Theme

Decide what overall education values are important to your family. Essentially you are creating a mission statement for your family’s homeschool.

A good starting question to ask yourself is: If I teach my child nothing, ever, what is it important that my child has absorbed living in our home? For our family our theme is, generally: learning is a privilege and a delight; don’t screw it up.

Many people’s answers will be education related, but others are not. Some families want to emphasize familial closeness or cooperation. This is your family; there is no wrong answer.

Remember, though, not to be too specific. Be general. Often I find with my friends that their mission statement could apply to everything they do as a family, not just the homeschool part.

Why this step matters:

When you are in the nitty-gritty of the school year and a problem pops up, sometimes it’s difficult to see what specifically isn’t working. Re-examining the difficulty from a more generalized vantage point often allows a better diagnosis of the problem, and gives us permission to change things.

STEP 2: Get Creative

Set aside a chunk of quiet time by yourself with no distractions (put that phone away!) This might be the most important step of all, and I encourage you to pencil a good block of time into your family’s schedule. If you have little kids, line up childcare so that you can close the door to your office or, better yet, leave the house.

Have a notebook handy to jot down ideas. If you’re the visual type, buy yourself a pretty notebook and nice pens (a new Moleskine and a medium tip Sharpie pen are pretty much heaven on earth). Spend time thinking about each child’s strengths, weaknesses, and goals, both longterm and short term. Jot every thought down; you never quite know how some seemingly benign thought will open up new opportunities.

Think about the past homeschool year. What worked? What didn’t? Write your answers down. Think about them. Chew on them. What would have made things run more smoothly? If you are preparing for your first year as a homeschool parent, think about your goals. Think about why you decided to homeschool, and what you’d like to accomplish, both broadly (I’d like my child to get into Harvard) and specifically (I’d like to teach my six-year-old to read).

By the end of this time, you probably will have a skeleton outline of what you would like your school year to look like (or, if you don’t, you could put one together by reviewing your notes).

Why this step matters:

I have learned countless things from this time with myself. Often little things that have been nagging at me reach that “a ha!” moment and forming a solution becomes simple. Often this time alone allows me to see patterns, and plan and change academics accordingly.

STEP 3: The Specifics

Now you’ve got a guidepost and a framework, and it’s time to get down to the specifics. Make this part work for you. Do you hate depending on the library? Then buy the books you need to reach your academic goals. Do you like specific, grid-like schedules that take you through the academic year? Make one. Do to-do lists motivate you? Then create your child’s courses and materials in the form of lists that you can check off regularly.

The purpose of the nitty-gritty to to create specific academics for your school year that stay true to your family’s theme, consider your child’s goals (or your goals for your child, as the case may be,) and that are tailored to work for you.

And it should be noted that, for some families, what works for them is a boxed curriculum that lays everything out for you every week. (If that’s the case, you’re done! Go back to the beach!)

Step three can take awhile. I sometimes spend hours agonizing how to divvy up specific books so that they will match up, timeline-wise, with some piece of historical fiction I have chosen for a particular child. Let me repeat what I said above: You’re making a plan that works for you. If you want to assign your child The Witch of Blackbird Pond while you’re studying ancient Greece, then do it! It’s your life and your family.

Step three can also involve a lot of research. If you have decided your daughter needs to focus on diagramming sentences and you’ve never done that before, you may need to spend some time researching what texts are out there and how you are going to plug that work into your school day.

Why this step matters:

By the time you are done, you will have all the materials you need for the school year ordered (or know where you can locate them), and a plan for how you are going to execute the day to day of your homeschool for your entire academic year, and that feels pretty great.

The Joys of Summer Reading

Serious reading time should be at the top of your summertime to-do list.

Serious reading time should be at the top of your summertime to-do list.

These days I read in bits and pieces. I take a book with me everywhere I go, so I can grab 15 minutes while I’m waiting in the dentist or 10 minutes waiting in the car for the kids to finish class. (I’d read at stoplights if I could.) Our family readaloud time can also get fragmented. We have a strict policy of reading together every night — except when dinner plans didn’t go as planned and we eat an hour later than normal, or someone isn’t feeling well, or we had a rough day homeschooling and my readaloud voice is shot, or whatever. On those nights we might cut our reading time in half, or forgo it altogether in favor of a group viewing of the latest episode of So You Think You Can Dance.

It sometimes feels like my reading progress can be measured in paragraphs instead of pages, so this time of year, I think back with longing to my childhood summers, when I could read uninterrupted for hours at a stretch. I’d pick the thickest books I could find, or check out every book in a series and stack them up beside me, devouring them like potato chips. With few distractions, I could get absorbed in a book in a way that’s much more difficult for me today. I can remember exactly where I was sitting in my grandmother’s living room, heart pounding, as Madeleine L’Engle’s A Swiftly Tilting Planet blew my mind. Another time I was reading science fiction in the hammock on the porch at home and suddenly looked up, startled and alarmed at the idea that I was outside breathing open air — until I remembered that I was on planet Earth and the air was okay to breathe.

A while ago, I was talking with a friend I’ve known since third grade (we bonded over The Chronicles of Narnia) and I said that while I was enjoying reading The Lord of the Rings with my kids, it was a much different experience from reading it on my own, on the long summer days, when I didn’t do much of anything but hang out in Middle Earth and worry about Ringwraiths. “I wish I’d been able to do that,” my friend said wistfully. I didn’t understand what she meant. I knew she was at least as big a Tolkien-nerd as I was, and we’d read the books about the same time.

“Don’t you remember?” she said. “My parents thought I read too much, so after half an hour I had to go play outside.” (My friend was much too well-behaved to do the logical thing and sneak the book out with her.) Clearly, if I had ever known about such traumatic events, I had blocked them from my memory. Of course, now that she is a grown-up with a full-time job and a household to support, it’s very nearly impossible for my friend to go back and recreate the summers she should have had, visiting other worlds and inhabiting other lives.

I’ve used her sad story as a cautionary tale in my own life. Whether we take a summer break or homeschool year-round (we’ve done both), I try to take advantage of the unique flexibility of homeschool life to make sure that my kids have the time and space to find their own reading obsessions. This year my younger son is tracking down The 39 Clues as quickly as the library can fulfill his hold requests, my 11-year-old daughter is matriculating at Hogwarts for the umpteenth time, my teenage daughter is spending a lot of time in various apocalyptic wastelands, and my teenage son is hanging out in small-town Maine with terrifying clowns. I can’t always join them (no way am I voluntarily reading about scary clowns), but I do try to schedule some marathon readaloud sessions, so that we can finally finish the His Dark Materials trilogy or get started with our first Jane Austen.

Occasionally (oh, happy day!) the kids will even ask me for reading suggestions, so I can pull out some recent favorites from the children’s/YA shelf. At the moment that list includes Museum of Thieves by Lian Tanner, about a fantasy world where parental overprotectiveness has been taken to such extremes that children are literally chained to their guardians. Leviathan, by Scott Westerfeld, is an alternate-history steampunk retelling of World War I, where the heroine disguises herself as a boy to serve on one of the massive, genetically modified, living airships in the British air force. Garth Nix’s Mister Monday envisions all of creation being run by a vast, supernatural bureaucracy, which our 12-year-old hero must learn to navigate to save his own life and ultimately the world (encountering quite a bit more adventure and danger along the way than we usually find in, say, the average DMV office). Each of these books is the first in a series, fulfilling my requirements for appropriate summer reading.

And as much as possible, I try to carve out some time for myself to grab my own over-large summer book — maybe Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, or Hilary Mantel’s Tudor epic, Bring Up the Bodies, or maybe I’ll finally tackle Anthony Trollope’s Chronicles of Barsetshire— and snuggle next to the kids to do some side-by-side reading, ignoring deadlines and household chores to get lost in a book together.

The Book Nerd: Planning Our Day Around Readalouds

There are lots of ways to plan your homeschool days — but readalouds are Suzanne’s favorite.

There are lots of ways to plan your homeschool days — but readalouds are Suzanne’s favorite.

Some people begin homeschooling because they want to tailor their child’s education to his or her individual needs. Others want to give their child the opportunity to explore a particular interest or talent. I decided to homeschool because I wanted to read to my kids.

It started with a story on the “new homeschool movement” that aired on NPR many years ago, back when my 15-year-old was a toddler. I don’t remember anything they said about the hows or whys of homeschooling, but I do remember that they had a clip of the mother of a homeschooled family reading Harry Potter aloud to her children as (described by the reporter) they all snuggled together on a large comfy chair. I loved it. It started me thinking that maybe homeschooling wasn’t such a crazy idea after all. It sent me to the library to check out a stack of how-to books, and ultimately it led to 10-plus years of homeschooling for the toddler and his three (eventual) siblings.

I do realize that you don’t actually have to homeschool to read to your kids — all my friends who send their children to school like normal people read to their children on a regular basis — but I found it easy to commit to a lifestyle that involved wearing pajamas after noon, eating dinner surrounded by stacks of curriculum, and lots of snuggling on comfy chairs. And, just like I’d imagined it, we have plenty of time for the intersection of my two favorite things in the world: my kids and books. It’s not a surprise that our days revolve around reading aloud.

We begin each homeschool day with Mom’s readaloud, a tradition that grew out of our daily struggle to get everyone up and out of bed for lessons. The prospect of math wasn’t very motivating first thing in the morning, but now we ease into our day with about 20 minutes of reading aloud. I get to pick the book, so I can sneak in those personal favorites that the kids have not quite gotten around to reading. (This is how I made sure my teenage son didn’t miss out on Little Women.) When we read The Neverending Story by Michael Ende, I found an edition just like the one I checked out from my local library 30 years ago, printed in green ink for the story of young Atreyu and his friend, Falkor the luckdragon, and their quest to save Fantastia, and in red ink for Bastian, who is reading Atreyu’s story and gradually discovering that he may be part of the adventure. I’m sure my library also had a copy of Elizabeth Enright’s The Saturdays, the first book in the Melendy Quartet, but somehow I never discovered it, so my children and I were introduced together to the four Melendy siblings, growing up in pre-World War II New York and pooling their money to create the Independent Saturday Afternoon Adventure Club.

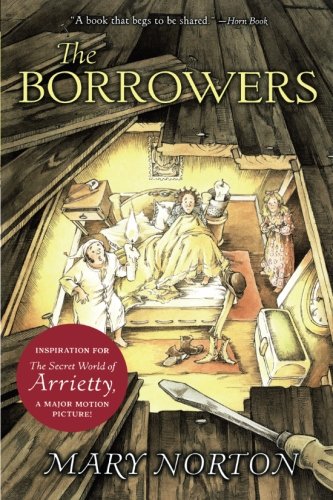

Another new acquaintance was Fern Drudger, modern day heroine of N.E. Bode’s The Anybodies, who discovers that despite being raised by tragically boring parents (they work for the firm of Beige & Beige and like to collect toasters), she actually belongs to a family with magical powers and a very special house made of books, where lunch is green eggs and ham and Borrowers live in the walls. We so enjoyed Fern (and her narrator, who likes to break into the action to complain about his old writing teacher) that we happily followed her through two sequels, The Nobodies and The Somebodies.

Once we’ve gotten around to math and our other morning lessons, we break for lunch and then gather together again on the couch for homeschool readalouds. We’ve done the same cycle of readalouds with each child, beginning with myths and legends from around the world, and moving on to adaptations of classic literature. It can be difficult to find adaptations that are clear to modern readers without sacrificing too much of the original story, but we always enjoy Geraldine McCaughrean, whose retellings of classic stories (from The Odyssey to One Thousand and One Arabian Nights to The Canterbury Tales and beyond) are witty and detailed. Another favorite retelling of an old story is T.H. White’s version of King Arthur’s childhood, The Sword in the Stone, which combines medieval culture and cheerful anachronism as it describes how Merlin turned the Wart (as Arthur was known) into various animals as part of his education. (T.H. White continues Arthur’s story in the rest of The Once and Future King, of which The Sword in the Stone is the first part, but the tone gets considerably darker and more adult, and I haven’t attempted that as a readaloud.) Towards the end of our readaloud cycle, we spend some time with Shakespeare and the best collection of adaptations I’ve found so far is Leon Garfield’s Shakespeare Stories and its follow-up, Shakespeare Stories II. Garfield also developed Shakespeare: The Animated Tales, a series of BBC-produced 30-minute versions of the plays which are fun and entertaining, along with being good warm-ups for full-length productions.

We end our day with evening readaloud, where each child gets to pick his or her own book. We’ve read everything from the Betsy-Tacy series to The Lord of the Rings, and a while back we spent several months working our way through all of Harry Potter, which involved lots of snuggling in Mom’s large comfy bed (as we don’t quite fit on a chair anymore). It was a lovely full-circle moment, but I’m happy to report that there’s no end in sight to our readaloud journey. I look forward to sharing more of our favorites for reading aloud or reading anytime, and I can’t wait to hear about yours. Happy reading!

6 Ways to Use Journals in Your Homeschool

Journals can help make writing part of your routine, build analysis skills, add a spine to special studies, and otherwise give your homeschool a surprising boost.

Journals can help make writing part of your routine, build analysis skills, add a spine to special studies, and otherwise give your homeschool a surprising boost.

Journaling is old stalwart of school literature classes — such a stalwart that many homeschoolers dismiss it out of hand, remembering boring afternoons of trying to fill up three pages about nothing in particular. Journals deserve a better reputation, though. Used properly, journals can help students develop confidence, not just as writers, but as thinkers and learners — and not just in literature classes, but across the curriculum.

“Journal writing is a way to personalize every aspect of your curriculum,” says a spokesperson for the research team at Saint Xavier University. “Ultimately a journal is a record of a student’s travels through the academic world.”

Want to make journaling part of your homeschool? Think of these suggestions as a sampler platter of opportunities: Feel free to try the ideas that seem right for your particular student, ignore the ones that don’t, and make all the adjustments that you know work for you. Experiment to figure out how journals work best for your student, and keep experimenting so that your methods grow and develop with your student. Like everything about homeschooling, journaling isn’t a “right-way” kind of activity but one that adapts to the particular learners you have.

Journaling works well as a low-tech investment: Though the idea of a big, fat journal full of empty pages may seem inspiring, some writers tend do better with very small, fill-up-able journals that need frequent replacement. Experiment with different sizes to figure out which is the best fit for your child — you may find that different sizes suit different purposes. (Happily journals can be fairly cheap!) Studies show that students do best if they get meaningful feedback on journal entries — but also that journals are less stressful when students know they’re private. Compromise by asking students to choose which entries you read.

1. Use a journal to encourage everyday writing

The more you write, the more your writing improves — especially if you have a space where writing is all about expressing your own ideas and thoughts and not about producing a final product that’s going to be evaluated critically.

“Journaling helps students make connections between what is really important to them, their curriculum, and their world,” says Kay Burke, author of How to Assess Authentic Learning. Some students may have lots of ideas about what they want to write, but for students new to journaling, a prompt can help a lot with getting started. One fun way to generate topics is to use a MadLibs approach: Brainstorm a list of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, and write them on strips of colored paper — blue for nouns, yellow for verbs, etc. Then, draw words to fill in the blanks of a simple sentence: A/an (adjective) (noun) (verb). Tack on a prepositional phrase — before breakfast, in springtime, at the zoo — to connect to something relevant to your child’s current life. Set a 9-minute timer, and let the writing begin.

Tip: This kind of journaling can be most effective if you do it, too.

2. Use a journal to build analysis skills

Think of two-column journaling as annotating with hand-holding: By literally drawing a line between the text and your own ideas, you’re encouraging students to engage directly with what they’re reading. For newbies or really challenging texts, you may want to keep it simple and ask students to simply summarize as they go, but as you get more comfortable, you can track things like themes and symbolism across readings. You can copy passages into a journal, but students can also treat this like a kind of advanced annotation and write directly in the books they’re reading. This kind of journaling works best when you’re writing right beside the text you’re writing about.

“Students make these connections all the time, but two-column journals push them to articulate and defend those connections,” says Burke. It’s often useful to steer new journal-ers toward one specific idea at a time — look for symbols of hope, or focus on this particular character — so that the possibilities don’t get overwhelming.

For new students, this can mean picking out short passages for them to start with. It’s easy to print a paragraph, clip or tape it inside your journal, and write on the opposite page. If your student is having trouble identifying passages to write about, you can prep a few for them to choose from so that it’s easy to get started. Sometimes it can feel like doing part of the “deciding what to write about” part for your student is too much handholding, but if the writing is the point, make it easy for them to get to that part. You can focus on identifying important passages another time if you want to focus on that skill. One of my big homeschool lessons has been that you’re much more likely to feel successful if you keep your focus on one thing at a time.

Tip: Start with a short poem, and give each line its own page.

3. Use a journal to encourage deeper thinking

When students are ready to move beyond summarizing what they’ve learned, it’s time to dive into the world of asking big questions. For some kids this comes naturally, but other students need a little more guidance, and journaling can provide a useful framework.

Ask students to jot down three questions they have after every new chunk of learning — it might be a chapter of a novel, a podcast about the Norman invasion, or a new math concept. Help students figure out if their questions are informational — are they clarifying something? — or theoretical — are they considering how ideas, implications, and assumptions extend beyond the text? Over time, students will have more and more theoretical questions and become better at recognizing where information gaps manifest in their learning, two things that push deeper thinking.

I talk more about how to encourage kids to ask questions using the Good Thinkers Toolkit in episode 4 of the Thinky Homeschool podcast. (link to the HSL Patreon)

Tip: This journal technique works best if you use it consistently.

4. Use a journal to support self-evaluation

Journaling can also be an effective way to encourage students to evaluate their own work. It may help to have a list of questions for students to work from: What was the most interesting thing about this assignment? How much effort did you put into it? Are you pleased with your results? What do you think is the best part of this project? If you’d had another two hours to work on it, what would you have done? Asking students to write a journal entry at the end of major papers and projects can give you meaningful insight into their thought process, effort, and achievement, says Art Young, editor of Language Connections: Writing and Reading Across the Curriculum.

Figuring out how to evaluate student progress can be tricky for homeschoolers, but kids get a lot of benefit out of assessing their own growth. Taking time to do this not only helps students see where they can improve in the future (thoughtful people will always be able to find something to improve), it also helps them identify places they’ve improved from the past, boosting their overall academic confidence.

Tip: Ask students to submit a journal with every big assignment.

5. Use a journal to add rigor to rabbit trails

One of the great things about homeschooling is being able to follow where our child’s interests lead, but it’s not always easy to figure out how these rabbit trails fit into your curriculum. Sometimes, that’s just fine — after all, everything you study doesn’t have to be about your transcript — but sometimes, a rabbit trail becomes a passion that you want to keep a record of. Journaling makes a lot of sense here — it’s low-effort, but provides a useful history should you need it.

Every week — or as often as seems appropriate — ask your child to jot down what they’ve learned or wondered or been inspired by in their chosen area of interest. You might end up with pages about Minecraft mods or records of kitchen experiments. Over time, kids may come back to certain topics over and over again — when you’re stuck trying to figure out a topic for a history project, flipping back through these journals reminds kids what gets them excited. Maybe they’ll be inspired to build a Roman village in Minecraft or to write a medieval cookbook.

6. Use a journal to spur discussion

One of the best ways to learn about literature is to talk about it with someone else, and for homeschoolers doing their curriculum at home, that someone else is likely to be you. How do you help your student get beyond plot summary and generalizations to deeper discussion? The micro-journal is one effective approach.

After you read something or cover a new topic together, take 5 minutes to jot down your big ideas and questions on an index card. (Stick to a small writing surface so that it feels easy to fill up with ideas.) Don’t worry about complete sentences or perfect phrasing — focus on getting down as much as you can. If it helps your student to have a focus, concentrate on connecting themes to other literary elements, like plot, character, or setting — that’s loose enough to include lots of ideas, but it gives thinkers a place to start. This on-the-fly brainstorming will help student push past their initial impressions so they can dig into material in a less superficial way.

Tip: It may help students if you ask a directing question before you begin brainstorming.

Secular Curriculum Review: IEW’s Student Writing Intensive

IEW’s Student Writing Intensive is a practical, step-by-step writing curriculum that works great for kids who think they hate writing.

IEW’s Student Writing Intensive is a practical, step-by-step writing curriculum that works great for kids who think they hate writing.

When my husband and I decided to homeschool our children, I thought writing would be a cinch to teach. I still think it would be, if I had a kid who was like me when I was a child — a child who was always writing. Growing up, I wanted to write poetry, stories, novels, you name it. And I never balked at a writing assignment.

Many people say that the secret to getting kids to write is to let them write whatever they want, and you can even take dictation for them, if you want. I think that’s good advice for a lot of kids, but my son is different. He doesn’t have any interest in writing anything. If I told him to write whatever he wanted, that would cause him anxiety and not make writing fun.

For a long time I wondered how I could teach him good writing skills without making him hate writing. This is something that I’ll be thinking about every year — how to move forward in a way that’s right for him. Fortunately, this year, I found something to get started with that’s working well. It’s the Institute for Excellence in Writing’s Student Writing Intensive Level A, which is for 3rd-5th graders. Levels B and C are available for higher grades. (Note that you can pair this with their Teaching Writing: Structure and Style, which is a 14-hour DVD Seminar for teachers and much more comprehensive. However, for the sake of this review, I’m writing about the Writing Intensive as a stand-alone curriculum.)

I’ll tell you right up front that I would not recommend this curriculum, if you have a child who enjoys writing. While all kids might benefit and learn something from it, I think it is especially made for kids who don’t have any idea what to write about or how to get started. I’m about halfway through the curriculum with my son right now.

It comes with a set of DVDs, and your child can watch the videos as if he’s sitting there in the classroom, listening to the teacher explain the concepts to a group of students. It begins by teaching students how to create a keyword outline for a paragraph that’s included in the lesson. Basically, he has to pick the three most important words in each sentence. Next, using this outline, he’ll write his own paragraph without looking at the original one. This has taken away the angst of “what am I supposed to write?” that was the first hurdle my son needed to get over.

Subsequent lessons are similar. All the lessons provide a pre-written text to create an outline with, but they add in “dress-ups” that the student needs to include in their paragraphs. Some of the dress-ups include a who/which clause, a strong verb, quality adjective, a because clause, etc. It’s slowly building a toolbox of writing mechanics that will help a child make her writing more varied and interesting. After doing these exercises with short, non-fiction paragraphs, it moves on to longer short stories and teaches students how to write a Story Sequence Chart. I can see where after doing these exercises with pre-written texts and re-writing them in his own words, my son may gain confidence in his writing ability and this will later free him up to begin some of his own, original writing. So far, I’ve been happy with it.

However, I have a few, small issues with this curriculum. First of all, some of the paragraphs he’s been using at the beginning of this curriculum should be proofread a little more closely. I have found more than one poorly written sentence. I always tell my son what is wrong with it, but for a parent who doesn’t have strong writing skills, I see this could be a problem. I feel a writing curriculum should offer excellent writing examples, though I also tell my son that this gives him a chance to write the paragraph better.

I also have a problem with forcing the student to use one of each dress-up in their paragraph. While I see the benefit of repetition so that the student becomes more comfortable with the using these sentence structures, and I love how it reinforces grammar skills, forcing every dress-up does not always make the best writing, especially in a short paragraph.

I have dealt with this issue by explaining to my son the purpose of these exercises. I told him that his writing will sound better if he varies the length and type of his sentences. He should try his best to use the dress-ups, but if they don’t serve the writing by making it sound better, he doesn’t have to do it. I go over his work with him, and I make suggestions, if I see a way to do it, but I don’t make him, for example, include a who/which clause into his writing, if I feel what he wrote without one is good writing.

This Student Writing Intensive offers some tips for kids that have been great for my son as well. The first one is that he’s only allowed to write with a pen. This takes away the urge to stop and erase and make the writing perfect the first time. The rough draft does not need to be perfect, and he’s learning proofreading marks to make corrections. The other tip that this curriculum offers is that a parent should be a walking dictionary for the child, telling him how to spell any word he doesn’t know. This takes a lot of angst out of writing that first draft too.

Overall, I like how this curriculum is helping my son put words on paper in a way that is not making him hate writing. It is a very formal program, which doesn’t work for every child, but if you have a child who has no interest in putting words on paper and/or likes having a “toolbox” to work with, it might be worth looking at.

If you use one of the Student Writing Intensives, IEW also offers continuation courses. I’m not sure whether that will be the right next step for my son, however. We’ll see when we get there.

6 Tips to Wrap Up Your Homeschool Year

Get your end-of-the-year record-keeping and organizing done so you can enjoy some time off.

Get your end-of-the-year record-keeping and organizing done so you can enjoy some time off.

It’s May and I’ve lost my mojo. I even doubled my caffeine intake to no avail.

It seems most every homeschooling parent gets to a point when they need to wrap up their school year. Even those parents that homeschool year-round, feel the pull of spring in May; the need to be done.

Homeschooling parents can quickly be overcome with the amount of material that’s accumulated throughout a long and creative homeschool year. Wrapping up the year can seem overwhelming. Here are some tips to get that clutter off your kitchen counter and put the homeschooling year to bed.

1. File end of year paperwork.

Be sure to file any end of year paperwork required in your district. Evaluations, portfolios, or other measures of progress, as well as letters of intent to homeschool, may be due now. Spend some time and get those out of the way so you can enjoy the summer days.

2. Update transcripts/report cards and evaluations.

Don’t wait for months to finalize report cards or evaluations. You will want to complete this task while the information is fresh in your mind. Tracking courses and progress is especially important if you are creating a transcript for your high schooler. Grades, field trips, courses, online classes, community groups, service projects, lab work, job experience, internships, apprenticeships, extracurricululars; all are easily lost or forgotten if not immediately recorded. Unschoolers should also record any classes, experiences or community involvement for their portfolio or transcript.

Unit studies can be easily put away in file folders labeled with the year or grade of the child.

If your child has completed a class through another organization, be sure to gather certificates of completion or grades from the teacher, if that is offered as part of the class.

Kids' school work can also be saved digitally. Take a photos and file in a folder for your portfolio or create a scrapbook of your incredible year. Grandparents especially love thumbing through scrapbooks and sharing memories with their grandchildren. Scrapbooks are also a great way to deter naysayers who might think your kids sat around eating Cheetos all year long.

3. Toss the rubbish.

What do you do with the hordes of paperwork that have accumulated? If your children are in their elementary years, save a few special pieces of artwork and toss the rest. The craft stores have pizza-style boxes that you can buy which are great for storing both artwork and academic work. The pizza boxes stack and store easily on a shelf, don’t take up much room, and hold a lot of material. Save one or two papers each month from each subject and toss the rest. I usually save one paper that shows beginning skills and one that shows mastery. My district/state doesn’t require evaluations of our work but I do save the boxes for three years and then get rid of them.

If you have many 3D sculptures, dioramas, hanging mobiles, and the like for art projects, it can be tougher to part with these masterpieces. Gifting the grandparents or aunts and uncles is a great way to share your homeschooling days with relatives. We always told our kids that if it didn’t fit in the storage box, we could not keep it. Certainly, a few special pieces were kept but the majority went into the box or were gifted away.

4. Clean up the extras.

Dump the moldy bread science experiment that’s been sitting on your shelf for weeks. Organize your homeschool space if you have one, clean off the desks, put the glue sticks and crayons back in their holders, give everything a good spring-time scrub down.

5. Label and store books.

I have a filing system for all of my books. At one point, I was homeschooling three kids in three different grade levels. The number of books, texts, instruction manuals, and other material accumulated through the years, was astounding. Before you pack everything up for the year, label the inside of every single book with an approximate grade level. Include chapter books, workbooks, and manipulatives in this process. I also place grade level stickers on the spines, so that when I store them, I can easily pull the next grade level I need for the coming year. Having organized books has been a lifesaver on so many occasions.

Donate, sell, or trade any items that you won’t use again. As my kids aged up through grades, I save curricula that was going to be used again. Any grade level items that we’d no longer use were donated or sold.

6. Plan some fun activities to celebrate

Get out of the house by planning some time with friends to celebrate the great weather. A picnic in the park, care-free playground days, lunch out with the kids, or a field trip can give you some much needed energy to push through those last few weeks of homeschooling.

Be proud of all your kids have accomplished this year. Don’t worry about the small things that didn’t get completed. Your children have likely learned so much exploring their own love of learning. Enjoy these last days and finish strong!

“What If?:” How We Started Homeschooling

It all started with a brochure. Patricia looks back on the first days of her homeschool life and the decision that — in retrospect — seems inevitable.

It all started with a brochure. Patricia looks back on the first days of her homeschool life and the decision that — in retrospect — seems inevitable.

Let me take you back, way back, to the fall of 1996. Maybe you were in high school or college, listening to Alanis Morissette and getting riled up, or maybe you were younger, watching Boy Meets World on TV every Friday night. Because I am probably older than you, I was a young mother of a four-year-old boy and a baby girl. The four-year-old wore overalls and a deep side part in his hair and looked a lot like Dennis the Menace. His sister had such big eyes that she kind of looked like Yoda, and some of the fattest legs you’ve ever seen on a baby. And I was their mother, still wearing little black skirts that hit mid-thigh, with tights and oxford shoes, smitten with the notion of homeschooling.

It started with a brochure. Which is a fancy word for a piece of paper folded in thirds, but it was 1996, and we still got information from pieces of paper. It was at the library, on a shelf. A piece of paper, folded in thirds, from the Northern California Homeschool Association, listing resources for homeschooling.

Homeschooling. I’d thought about it when Henry was two, and I met the first homeschoolers I’d ever come across, a family with five kids. The kids didn’t go to school — none of them. They didn’t go to school! I was a former elementary teacher and the whole notion was as inconceivable to me as the concept of email in those days. Still, I was intrigued enough to find a book about home- schooling at the library, and played with the idea for a few weeks that fall. But ultimately I lay in bed thinking about lunchboxes, and school Halloween parades, and playing tether ball on the blacktop at recess. I thought about Septembers and the new shoes that came with them. My heart jittered as I flipped through the losses. Homeschooling meant walking away from the American childhood experience, and I just couldn’t do that to Henry.

When I picked up that brochure two years later, something had changed. Maybe it was that I knew Henry better now, or maybe it was how kindergarten lurked in my peripheral vision. Or maybe it was something inexplicable, like the way the boy who grew up down the street had a different gleam about him one day in pre-algebra class, and suddenly you couldn’t stop writing his name on the inside flap of your Pee-Chee folder.

It did feel a little like puppy love. I picked up that brochure and, like that, the idea of homeschooling wrote itself into every margin of my mind. I researched it at home, dialing up AOL on our computer — dial-tone, beeps, static, that unforgettable spring-sproing, rocket launch fuzz — and after two or three attempts got connected. Do you remember the Internet in 1996? How you spent more time looking at that little hourglass icon than you did actual content? How the images revealed themselves slowly, top to bottom, like a theater curtain in reverse? None of this seemed unreasonable to me back then; it was just what it took to get to the homeschooling message boards I found and lingered on that fall. People — mostly mothers — posted questions or shared their homeschooling experiences, and others responded. I scrolled and scrolled, searching for posts that might answer my concerns. How do you meet homeschooling friends? What do kids miss out on when they don’t go to school? How do you tell your in-laws? I clicked and hoped, clicked and hoped. Sometimes it took a full minute for a new page to load. There was a lot of bickering about what did and didn’t constitute unschooling, but what struck me most was the community on those boards. Homeschoolers were real, connecting with one another! What started as a wisp of a notion gathered the weight of possibility.

What if? What if Henry didn’t go to school the next fall? What if we found a local community of homeschoolers? What if I didn’t have to send my kids off to some other teacher’s classroom, while I got a job teaching other people’s kids? The possibilities glittered brighter than a new lunchbox.