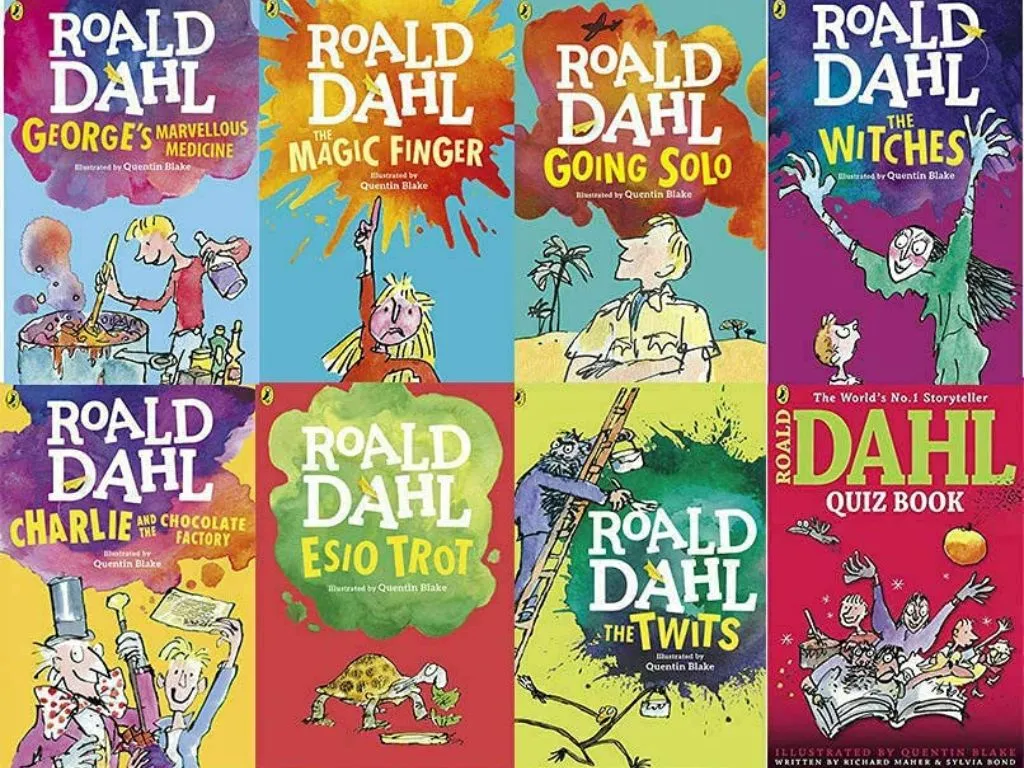

What to Read Next If You Like Roald Dahl

If you love the fantasy, fun, and humor of Roald Dahl, you’ll enjoy these books that capture some of that same playful spirit.

Madcap hijinks and memorable characters are the best ways to celebrate the (not uncomplicated) writer who brought us Willy Wonka and the BFG.

The Adventures of Nanny Piggins by R.A. Spratt

When miserly Mr. Green hires a pig to nanny his three children in an effort to save money, he has no idea what hilarious adventures await them with the sassy, sharp-dressed caretaker. Mr. Green is a classic Dahl-esque villain (his job involves helping rich people avoid paying taxes, and he has zero interest in spending time with his children), and Nanny Piggins brings a Pippi Longstocking-style madness to the Green children’s lives — she’s definitely not a real-life role model, but this isn’t supposed to be a real-life kind of book. As with so many of Dahl’s books, that’s part of its wacky charm. (Early Grades)

Karlson on the Roof by Astrid Lindgren

Fun and chaos ensue when Eric spots a funny man with a propeller on his back who happens to live on Eric’s rooftop. Karlson is very rude and annoying — he kind of reminds me of the cat in Dr. Seuss, who runs around making chaos and messes without ever having to deal with the consequences (I had no idea I could identify so much with a fish!), but that kind of whimsical chaos is definitely the stuff of Dahl. (Early Grades)

The Perilous Princess Plot by Sarah Courtauld

There’s nothing predictable about this fractured fairy tale, starring two sisters from The Middle of Nowhere who end up on a wacky adventure. Lavender is obsessed with being a princess, but when she’s kidnapped by an ogre, her little sister Eliza (who does not want to be a princess or discuss princesses at all, thank you very much) sets off on a rescue mission — whether Lavender wants her to or not. The sibling dynamic is a big part of the fun here. (Early Grades)

The Scandalous Sisterhood of Prickwillow Place by Julie Berry

When someone murders the decidedly unpleasant headmistress of St. Etheldreda's School for Girls, the school’s young-ladies-in-training decide to cover up the crime and keep the school going. I love the idea of Victorian “bad girls” (who are interested in devilish things like science and finance) going rogue and taking over their school to run it the way that suits them, even if it means going to great lengths to convince their community that their headmistress is still alive and chaperoning them appropriately. (Middle Grades)

Mr. Stink by David Walliams

Chloe befriends the town tramp and hides him in her backyard garden shed in this story from Little Britain star Walliams that’s equal parts funny and touching. (How can you resist a book with lines like “Mr Stink stank. He also stunk. And if it was correct English to say he stinked, then he stinked as well…?”) This is one of those readalouds that you have to stop mid-sentence to let the giggles subside. (Middle Grades)

You're a Bad Man, Mr. Gum by Andy Stanton

The truly terrible Mr. Gum has the prettiest garden in town in this darkly hilarious novel. Mr. Gum is as deliciously awful as the best Dahl bad guys, but there are also of other delightfully weird characters, including the enormous dog Jake who is a particular target of Mr. Gum’s rage and Jammy Grammy Lammy F’Huppa F’Huppa Berlin Stereo Eo Eo Lebb C’Yepp Nermonica Le Straypek De Grespin De Crespin De Spespin De Vespin De Whoop De Loop De Brunkle Merry Christmas Lenoir (you can call her Polly). The fairy who smacks Mr. Gum with a frying pan when she’s angry at him was a favorite in our house. (Early Grades)

Groosham Grange by Anthony Horowitz

Horowitz’s absurd horror story centers around David, whose awful parents ship him off to an equally awful—and deliciously creepy—boarding school. You might think this book is borrowing from Harry Potter — a magical school reached by train, students teaming up to fight evil forces, a boring history teacher who is actually a ghost — but Groosham Grange was actually published first. Horowitz, like Dahl, enjoys leaning into the dark side and laughing. (Middle Grades)

Good Omens by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman

I will never stop recommending this collaboration by two of my favorite British writers—a rip-roaringly funny apocalyptic story. When the Antichrist ends up being raised in a typical British town, a Witchfinder-in-training falls for one of the witches he’s supposed to be investigating, and a demon and an angel team up to save humanity from the Apocalypse, you know some crazy things are going to happen. (High School)

The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

Wilde’s wacky tale of intentional and accidental mistaken identity in very proper society is a delightful romp. Jack and Algernon both have secret lives that crash into each other spectacularly at a Very Polite country house weekend. My high school students laugh out loud the whole time we’re reading this play. (High School)

Peter Nimble and His Fantastic Eyes by Jonathan Auxier

When a blind boy who happens to also be a master thief steals three sets of magical eyes from a mad haberdasher, he’s propelled into an unexpected adventure. This has a little bit of a weird fairy tale vibe, but the fantastic characters and often-surprising plotting will definitely appeal to Dahl fans. (Middle Grades)

Which Witch? by Eva Ibbotson

Evil enchanter Arriman must find a bride if he hopes to ever retire, so he sets up a wicked contest to discover his witchy mate. White witch Belladonna, who is desperately trying to convince everyone she’s wicked, has a Dahl heroine’s plucky sensibility, and the real wicked witches are delightfully evil.

(Middle Grades)

The Joys of Summer Reading

Serious reading time should be at the top of your summertime to-do list.

Serious reading time should be at the top of your summertime to-do list.

These days I read in bits and pieces. I take a book with me everywhere I go, so I can grab 15 minutes while I’m waiting in the dentist or 10 minutes waiting in the car for the kids to finish class. (I’d read at stoplights if I could.) Our family readaloud time can also get fragmented. We have a strict policy of reading together every night — except when dinner plans didn’t go as planned and we eat an hour later than normal, or someone isn’t feeling well, or we had a rough day homeschooling and my readaloud voice is shot, or whatever. On those nights we might cut our reading time in half, or forgo it altogether in favor of a group viewing of the latest episode of So You Think You Can Dance.

It sometimes feels like my reading progress can be measured in paragraphs instead of pages, so this time of year, I think back with longing to my childhood summers, when I could read uninterrupted for hours at a stretch. I’d pick the thickest books I could find, or check out every book in a series and stack them up beside me, devouring them like potato chips. With few distractions, I could get absorbed in a book in a way that’s much more difficult for me today. I can remember exactly where I was sitting in my grandmother’s living room, heart pounding, as Madeleine L’Engle’s A Swiftly Tilting Planet blew my mind. Another time I was reading science fiction in the hammock on the porch at home and suddenly looked up, startled and alarmed at the idea that I was outside breathing open air — until I remembered that I was on planet Earth and the air was okay to breathe.

A while ago, I was talking with a friend I’ve known since third grade (we bonded over The Chronicles of Narnia) and I said that while I was enjoying reading The Lord of the Rings with my kids, it was a much different experience from reading it on my own, on the long summer days, when I didn’t do much of anything but hang out in Middle Earth and worry about Ringwraiths. “I wish I’d been able to do that,” my friend said wistfully. I didn’t understand what she meant. I knew she was at least as big a Tolkien-nerd as I was, and we’d read the books about the same time.

“Don’t you remember?” she said. “My parents thought I read too much, so after half an hour I had to go play outside.” (My friend was much too well-behaved to do the logical thing and sneak the book out with her.) Clearly, if I had ever known about such traumatic events, I had blocked them from my memory. Of course, now that she is a grown-up with a full-time job and a household to support, it’s very nearly impossible for my friend to go back and recreate the summers she should have had, visiting other worlds and inhabiting other lives.

I’ve used her sad story as a cautionary tale in my own life. Whether we take a summer break or homeschool year-round (we’ve done both), I try to take advantage of the unique flexibility of homeschool life to make sure that my kids have the time and space to find their own reading obsessions. This year my younger son is tracking down The 39 Clues as quickly as the library can fulfill his hold requests, my 11-year-old daughter is matriculating at Hogwarts for the umpteenth time, my teenage daughter is spending a lot of time in various apocalyptic wastelands, and my teenage son is hanging out in small-town Maine with terrifying clowns. I can’t always join them (no way am I voluntarily reading about scary clowns), but I do try to schedule some marathon readaloud sessions, so that we can finally finish the His Dark Materials trilogy or get started with our first Jane Austen.

Occasionally (oh, happy day!) the kids will even ask me for reading suggestions, so I can pull out some recent favorites from the children’s/YA shelf. At the moment that list includes Museum of Thieves by Lian Tanner, about a fantasy world where parental overprotectiveness has been taken to such extremes that children are literally chained to their guardians. Leviathan, by Scott Westerfeld, is an alternate-history steampunk retelling of World War I, where the heroine disguises herself as a boy to serve on one of the massive, genetically modified, living airships in the British air force. Garth Nix’s Mister Monday envisions all of creation being run by a vast, supernatural bureaucracy, which our 12-year-old hero must learn to navigate to save his own life and ultimately the world (encountering quite a bit more adventure and danger along the way than we usually find in, say, the average DMV office). Each of these books is the first in a series, fulfilling my requirements for appropriate summer reading.

And as much as possible, I try to carve out some time for myself to grab my own over-large summer book — maybe Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, or Hilary Mantel’s Tudor epic, Bring Up the Bodies, or maybe I’ll finally tackle Anthony Trollope’s Chronicles of Barsetshire— and snuggle next to the kids to do some side-by-side reading, ignoring deadlines and household chores to get lost in a book together.

Real Life Secular Homeschool Stories: What It’s Really Like . . .

Ready to be inspired? Real homeschool families answer the question we all want to ask: “How do you do it?” From managing the education of a big family to dealing with depression to traveling around the country in a 150-square-foot RV, these families make homeschool life work on their own terms.

Ready to be inspired? Real homeschool families answer the question we all want to ask: “How do you do it?” From managing the education of a big family to dealing with depression to traveling around the country in a 150-square-foot RV, these families make homeschool life work on their own terms.

What it’s really like to go away to college after homeschooling

I guess I always kind of thought I would go to college. My mom and dad both went, and they had lots of friends from college and told lots of stories about their college days. And as I got older, I knew that I wanted to study veterinary medicine, which is something you kind of have to go to college to do.

When people find out I was homeschooled, they often ask me if it’s weird to go from being home all day with my mom to living on a college campus. And I guess that would be pretty weird! But that’s not what it was like for me. I was homeschooled all the way through, from kindergarten through 12th grade, but it’s not like I spent every day at home. We always had park days and activities, and I usually took a few outside classes — I took history at our homeschool co-op and karate at a dojo and other stuff here and there. In high school, I started taking dual enrollment classes at a nearby college. By the time I was a senior, I was spending half of my week on a college campus. I’m not sure how much better prepared for college I could have been!

I actually think I was more prepared than a lot of students who went to school. One of the girls on my hall had no idea how to use a washing machine. I had to show her how to sort her clothes and get the machine started. She’d never washed her own clothes. I’ve been doing laundry since 6th grade — and cooking my own meals and cleaning up my own messes. I think all those dual enrollment classes served me well, too. Not because I learned so much but because I learned how to do things like talk to professors and navigate the campus. I notice that a lot of students are kind of shy or hesitant about approaching professors, but I’m totally comfortable taking advantage of office hours. One of my professors offered me a lab internship next year that I didn’t even apply for — I’d just been talking to her about internship opportunities over the course of the year, so she thought of me when one came up.

I know how to manage my time and my workload, too, because my parents gave me a lot of responsibility for that in high school. I think it helped a lot that my parents gave me a lot of freedom to mess up. One time, back in 5th or 6th grade, I signed up to do a history fair project at our co-op. I was really excited about it, but I flaked on doing the work and ended up throwing the project together the night before. I was so embarrassed seeing my slapped-up posterboards surrounded by everybody else’s cool projects. I learned that I have to care about my work more than anybody else does — and that’s something that has served me really well in college.

—Ginny*, sophomore in college and former homeschooler

What it’s really like to homeschool a big family

When people find out I homeschool five kids ages 2 to 15, they always ask me how we do it. The honest answer is that I don’t know — and that sometimes we don’t do it very well! It’s much easier now that most of the kids are older — they can work independently, get their own snacks, help each other out. In fact, at this point, it’s probably easier to homeschool them than it would be to get everybody up and dressed and ready to catch a bus in the morning. (I don’t know how people do that!)

In my life before kids, I would never have called myself an organized person, but homeschooling has forced me to become one. Without structure, our life would be impossible. I don’t know how I’d make sure we covered the academic bases with each kid if we didn’t stick to a pretty detailed schedule. At the same time, I have to be really flexible — if Sasha gets chosen for a ballet performance, we have to make time for getting to and from rehearsals, or if one of the kids comes down with a cold or the toddler refuses to take her nap, I have to improvise. On the other hand, sometimes there are days where we have a little extra time — the toddler naps longer or our math lesson clicks right away — and I try to make the most of that time. I actually keep a to-do list just for unexpected extra time so that I’m not just standing there with my mouth open in surprise until it ends.

I’ve learned over the years that the moments when we’re really connecting as a family, all working together, are some of my favorite parts of homeschooling. When I give those up, I feel more frustrated, less patient, less sure I’m doing a good job as a homeschooling mom. So I make sure we always have one subject we do all of us together — it’s nature study now, but we’ve done art and history together in the past. I think it’s good for the kids, too, but it’s something that I do for me.

As the kids get older, I’ve found that they can be a great help. Right now, my 10-year-old is teaching my 5-year-old math. Not only is Daniel loving learning from his big brother, it’s also reinforcing Ryan’s math skills and improving his math confidence. That’s what I call a win-win.

I also rely on the kids to help around the house. The way I see it, homeschooling them is my full-time job, and keeping up with the house is everybody-who-lives-here’s job. Even the littlest kids get chores. I make a monthly meal plan, which sometimes makes me feel a little blah about cooking, but ultimately, three meals and umpteen snacks a day is just too much for me to cope with on the fly.

We do have to sacrifice some things. We can’t really handle more than one outside class/activity per kid — I’d basically be running a taxi service if we tried to do more than that. And the younger kids sometimes have to wait a year on something they want to do because of the older kids’ commitments. That might get easier when Sasha starts driving next year.

Because we’re so scheduled, I try to shake up the routine every once in a while — take a day to play outside just because it finally feels like spring, rent a bunch of movies and make popcorn for a movie marathon, bake cookies after breakfast. I have to be so organized to make it all work that sometimes I start to feel like a draconian taskmaster rather than the fun mom I want to be. Fun days remind all of us, especially me, that we homeschool because it’s smart and good and right for us — but also because it’s fun.

—Kathryn*, homeschool mom to Sasha (15), Eric(13), Ryan (10), Daniel (5), and Ellie (2)

What it’s really like to work full-time when you’re homeschooling

Going back to work wasn’t the plan. When I quit my nursing job after Erin was born, I thought I was done with the working world for good. And for 22 years, I was. Then, my marriage fell apart, and I had to go back to work. Erin was already in college and Josh was about to graduate, but Stephen was just finishing 8th grade. We talked a lot about what to do: The schools near us aren’t bad, and Stephen is a good student. I thought he’d be OK there. But he was adamant that he wanted to keep homeschooling, so we’ve been figuring it out together. I do 12-hour shifts, three days on, two days off, so he does a lot of independent work. We plan out his assignments a month at a time — he doesn’t love that, but it’s the only way I have the space to plan things. He works on his own on my work days, and on my off-days, we check over his work together and talk about what’s interesting or what’s confusing. I also have to run errands, do housework, and manage everything else on those days, so it’s hard. It’s exhausting. But I see how hard he’s working, and it inspires me to keep at it.

—Lora*, mom to two homeschool grads and one homeschooled high-schooler

What it’s really like to live without a TV

Honestly, I don’t think it’s that different from living with a television. We got rid of our television set three years ago, and we really haven’t missed it. We read a lot and play a lot of games and work on a lot of big puzzles — we almost always have a big jigsaw puzzle going on the table in the dining room. We go to movies now and then, and the kids play Minecraft, and sometimes we’ll watch a documentary on the computer, so I wouldn’t call us screen-free. But I do feel like I am more intentional about my downtime, and I like that a lot.

—Emily*, homeschool mom to 10-year-old and 8-year-old boys

What it’s really like to homeschool a gifted child

People always said “Oh, she’s so smart,” and I noticed that she did a lot of things earlier than other kids — I remember her putting together puzzles all by herself before she was 3 — but I was still surprised when she scored 180 on a MENSA I.Q. test when she was just 10. We were already homeschooling Maggie when we found out she was gifted. I think we would have made the same decision if we had known. Homeschooling gives us a lot of flexibility. We can move at Maggie’s pace, which is often a lot faster than schools can move, but we can also slow down when we need to. There’s no busy work! And no waiting on anyone else to get it. It’s hard sometimes, though, because your kid is your kid, but sometimes it feels like whatever you say comes across as bragging. Or worse, you’ll seem like one of those Tiger Moms, pushing your kid too hard too fast. (Which you worry about all the time anyway. Am I pushing hard enough? Am I pushing too hard? It never ends.) Other parents at the playground don’t have to weigh their words to talk about things like reading lists and math scores, but I always do.

—Kim*, homeschool mom to 12-year-old Maggie

What it’s really like to homeschool when you’re depressed

At first, I didn’t know I had a problem. It just felt like a bad day, but the bad day kept coming. Just getting out of bed in the morning felt like it used up every scrap of energy I had. The prospect of making breakfast was more than I could handle — I felt so annoyed when the kids didn't want something easy, like cereal or toast, that they could get for themselves. They were younger then — my oldest was just in 2nd grade when my symptoms started — so they really did depend on me for a lot. And I was always letting them down. They’d want to take a class at our co-op, but I was too overwhelmed by having to call to sign up, so we’d miss the deadline. They’d want to go to a museum exhibit, but I’d keep putting it off until the exhibit was gone. They’d want to play at the park with friends, but I couldn’t make myself call the other moms to set something up. Every night, I’d lie awake thinking “Tomorrow will be better. Tomorrow we’ll go to the nature center and read books and have fun. Tomorrow I’ll make it up to them.” I felt guilty pretty much all the time.

I slept so much, but I was tired all the time. My phone’s voice mail filled up with messages I couldn't make myself listen to. Laundry piled up. The kids were spending their time playing video games and watching television instead of doing school work. And I was just moving in this haze, constantly telling myself that tomorrow would be different, tomorrow would be better.

Finally, my husband said, look, I think you should talk to someone, I think you might be depressed. I was honestly horrified. Mothers aren’t supposed to be depressed, especially stay-at-home mothers, especially stay-at-home homeschooling mothers. Wasn’t I supposed to get all the happiness I needed from taking care of my family and spending time with my kids? Wasn’t that what I had wanted? Wasn’t that why I had quit my job to stay home with the kids? What was wrong with me? Thank goodness he pushed, and I finally went to see a doctor. She prescribed me some medication, which I was really resistant to taking, and scheduled me for therapy.

I couldn’t believe what a difference the medication made. Suddenly, I felt awake again. A week after I started seeing my doctor, I woke up early and made scrambled eggs with bacon and hash browns for breakfast. The kids came into the kitchen and watched, like they were seeing a unicorn or something rare and amazing. We fell back into a routine of school work and park days.

Medication and therapy made a big difference, but depression isn’t something that magically goes away. I still have days where I don’t want to get out of bed, where all I want to do is sit on the couch. But I’ve learned to accept those days because they’re the exception rather than the rule now. A bad day is just a bad day (or a bad week sometimes), not a sign that I am a bad mother. Feeling guilty just makes me feel more depressed.

—Jennifer*, homeschooling mom to a 9th grader and a 6th grader

What it’s really like to homeschool for $0

My kids are young, so it’s probably easier, but I don’t spend any money on homeschooling. That was the deal we made — I could quit work and homeschool as long as our expenses stayed the same. I don’t even look at other people’s curriculum stuff because there’s no way I’m going to spend money on it, but there is a lot of good free stuff. I think there’s free stuff that’s better than curriculum you can pay for. What it costs is time because I have to spend a lot of time on the library website and searching online for materials. but they’re there. I just have to keep hunting until I find the right one and know that it sometimes takes longer than I want it to.

—Rachel*, homeschool mom to three kids

What it’s really like to homeschool on the road

We’ve been homeschooling since Amelia was in first grade, and Henry has never been to a traditional school. The idea of roadschooling just kind of happened. My partner and I have always loved traveling, and we spent a big chunk of our pre-kid days in planes, trains, and automobiles. Money and mobility slowed us down after Amelia was born, but one of us was always saying ‘Oooh, it would be so cool to take the kids here’ or ‘We’ve gotta plan a trip there.’ We wondered what we were waiting for, so we started planning a cross-country road trip with the kids. That morphed into buying an RV — after all, we’d be saving lots of money on hotel rooms, right? And once we had the RV and had done a couple of long weekends in it, we thought ‘Why don’t we just live this way?’ It felt right, way more right than living in the suburbs had ever felt to either of us. So we sold our house in Tennessee and most of our stuff (we still have some stuff in a storage space in Texas, where my mom lives) and headed out to explore North America.

I know we’re lucky to be able to make it work. Not everyone could. My partner does medical transcription work, which she can do from anywhere, but we do sometimes hit panic mode when WiFi is spotty for miles on end. We’ve checked into a hotel a couple of times so she can get her work done. I do freelance writing, so as long as I make my deadlines, I can work anywhere. We don’t make a ton of money, but we make enough to live a simple life and travel when we want to, which is all we need. Our permanent address is my mom’s place in Texas, which means we don’t have to worry about school paperwork for the kids — Texas is totally relaxed when it comes to requirements for homeschooling.

We’ve been on the road for almost a year now, and every week is different. Originally, I thought we would do all this research before visiting different sites, but it’s turned out to be the reverse — seeing sites, visiting museums, and experiencing different places is what makes us want to learn more about them. Another idea I had was for the kids to keep travel journals — to write down their experiences on the road — but they weren’t really interested in that. So I thought I’d keep a family travel journal instead. Of course, seeing me journaling made them want to participate, so now we all take turns writing in the journal. I love flipping back through the pages and remembering how many things we’ve done together. We have also become huge fans of the Junior Ranger program at the National Parks — the kids love completing the activities to earn badges.

The hardest thing is probably having such limited space. We have to be really selective about what we keep with us, and I’m always wishing I’d brought different books. There’s always something I want that’s in our storage locker! But thank goodness for laptops and e-readers, which have saved the day more than once.

—Carole*, homeschool mom to two roadscholars

*last names removed for online publication

How do we catch up when we’re behind in math (or anything else)?

Our student is testing behind in math — how worried should we be about getting caught up asap?

My sixth grader is really behind in math. She was struggling when we pulled her out of school last year, and she’s still scoring at least one grade level behind in every placement test. I don’t want her to stress about math, but I also don’t want her to keep falling behind. How can we catch up?

I’m going to answer the question that you’re asking, but first I’d like to tell you something that I think might reassure you. My husband teaches high school math, and over the last five years, he’s become a popular tutor for unschoolers who want to take the SAT or ACT. Most of these kids come to him with no formal math experience — many don’t know their multiplication tables or that decimals and fractions describe the same thing. He usually gets them about a year or two before they want to actually take the test, but sometimes they only have six months together. And you know what? All of these kids have always learned enough math in that time to get a decent score on their official tests. Obviously this isn’t the strategy you’re taking with your daughter — but isn’t it kind of reassuring to know that even if you do fall behind, catching up is easier than you probably think it is?

On to your question: If your daughter’s placement tests are putting her a year behind, I’d forget forging ahead and instead let her work at the level she’s ready for. There are a couple of reasons for this. First, you don’t have to hold onto rigid ideas about grade levels when you are homeschooling. I bet you wouldn’t worry if your daughter were a year ahead in math, right? The longer you homeschool, the more you’ll realize that grade levels are kind of arbitrary, and the important thing is to choose the work your child is ready for, whatever the number on the workbook happens to be. Second, there’s a good chance that your daughter just missed a foundational step in math that’s making it hard for her to move forward — she might have missed a few days of class or had a not-great teacher or just not been ready to make the mental connection. There’s a really good chance that if you go back and work through that grade level together, she’ll pick up what she needs to know and be ready to move on — maybe in less time than you think. (And sometimes it helps to play out the worst case scenario because it’s not as bad as you thought: What if your daughter is always a level behind in math? Maybe she won’t take calculus in high school, which isn’t terrible unless she has her heart set on taking calculus or a career in engineering.) Remember: You don’t have to follow the math book problem for problem. You can find the areas that are tripping her up and spend most of your time on those, and move on as she masters concepts. By not making a big deal about “being behind,” you’re also teaching your daughter that it’s more important to understand something and be able to put it to use than it is to learn just enough to get through a set of test questions.

At the same time, consider ways you can make math more of a part of your everyday life. Stock up on board games that make math fun (see the spring 2017 for ideas) and living math books. Use an alternative approach to math, like Simply Charlotte Mason’s Pet Store Math, which lets kids pretend they’re the bosses of their own pet store, or Life of Fred, which turns math into a playful readaloud. (Life of Fred isn’t secular, but I feel like the places where it’s not are so ridiculously over-the-top that it’s easy to discuss them as you go.) Encourage kids to use math in everyday life: Split your pizza into eight even pieces, double a cupcake recipe for a party, or see if your budget will stretch to that new video game. There’s so much math in life that it’s not hard to find opportunities to just do it, without a formal book or any worry about what level it is.

I honestly think a combination of these two strategies—being okay with starting at the level where your daughter is and increasing the numeracy, or math literacy, quotient of your home—will help your daughter’s mathematic knowledge increase significantly. But if you’re really concerned about getting her up to a specific grade level, double-time your way through the math she tests into—if you’d usually do three lessons a week, do five or six—until she’s working at grade level. Really, though, I think this is a place where going with your daughter’s flow and trusting that she’ll get where she needs to go if you keep working together will serve your homeschool best.

8 Ways to Celebrate the End of the Homeschool Year

Even if you’re a year-round homeschooler, late spring marks the end of lots of regular activities and is a great time to throw an end-of-the-year celebration for your homeschool.

Celebrating milestones like the end of the school year can be an important part of keeping joy alive in your homeschool, so pause to appreciate that you’ve made it through the year together.

Even if you’re a year-round homeschooler, late spring marks the end of lots of regular activities and is a great time to throw an end-of-the-year celebration for your homeschool. Celebrating milestones like the end of the school year can be an important part of keeping joy alive in your homeschool, especially as students move into middle and high school, so pause to appreciate that you’ve made it through the year together. Here are a few of our favorite ways to mark the end of the academic year:

Make a time capsule.

Add a few items that sum up the year: a favorite book, a CD with your in-regular-rotation tunes on it, pictures of fun science or history projects, and a favorite artwork or two. Ask your student to write a letter about her year, and add a letter of your own highlighting some of your favorite memories from the year. (Not that you have to think this far ahead, but you could open these boxes together to celebrate your student’s last day of high school.)

Take a camping trip.

Unplug literally by heading to the nearest campground and spending the night in the great outdoors. (If you’ve never camped before, many state parks have special newbie camper programs that set you up with gear and on-site assistance. Finishing up your last official readaloud by the campfire and toasting your year’s highlights while star-gazing is definitely a memorable way to celebrate finishing another grade.

Have an end-of-the-year scavenger hunt.

Bonus points if you can tie some of your clues to the year’s highlights: Find a plant mentioned in a Robert Frost poem, find a substance with a pH level of 7.0 or higher, find a historical marker that refers to the Civil War, etc. Do a little advance planning to choose your site and clues.

Make the world a better place.

Helping others can be a great way to celebrate — consider spending your last month of school collected canned goods for a food kitchen or dog food for an animal shelter and making your donation together on your last day of school. If you’re taking a summer break, consider signing up for a recurring volunteer opportunity during the summer — for example, kids can ride along on Meals on Wheels deliveries or participate with you in park clean-up days.

Freshen up your homeschool space.

By the end of the year, half the pencils are stubby, the bookshelves are sloppy, and everything’s just kind of a mess. Celebrate the end of the year by making your space beautiful again: Clean it from top to bottom, consider brushing on a fresh coat of paint, and update chair cushions or throw pillows to make everything feel new and shiny again.

Host a lawn games party.

Break out the classics: badminton, croquet, cornhole, water balloons, and bocce ball, and spend the day competing in old-fashioned outdoor games. If you want, keep score and award paper medals to the people who do the best in each category. A day like this is a fun way to officially welcome summer to your homeschool.

Go out for afternoon tea.

Something about a classic high tea feels so special, which is what makes it such a lovely way to celebrate the end of another year. Check high-end hotels and tea rooms in your area to find a place that serves high tea, make reservations, and wear your fancy best to nibble and sip your way through the afternoon.

Have a pajama party.

Spending the day in your pajamas is the epitome of homeschool life, right? Cozy up in your PJs with a movie marathon (rent the Harry Potter flicks or all the Studio Ghibli films), eat pancakes or waffles for dinner, and enjoy your well-earned day of rest.

The Book Nerd: Planning Our Day Around Readalouds

There are lots of ways to plan your homeschool days — but readalouds are Suzanne’s favorite.

There are lots of ways to plan your homeschool days — but readalouds are Suzanne’s favorite.

Some people begin homeschooling because they want to tailor their child’s education to his or her individual needs. Others want to give their child the opportunity to explore a particular interest or talent. I decided to homeschool because I wanted to read to my kids.

It started with a story on the “new homeschool movement” that aired on NPR many years ago, back when my 15-year-old was a toddler. I don’t remember anything they said about the hows or whys of homeschooling, but I do remember that they had a clip of the mother of a homeschooled family reading Harry Potter aloud to her children as (described by the reporter) they all snuggled together on a large comfy chair. I loved it. It started me thinking that maybe homeschooling wasn’t such a crazy idea after all. It sent me to the library to check out a stack of how-to books, and ultimately it led to 10-plus years of homeschooling for the toddler and his three (eventual) siblings.

I do realize that you don’t actually have to homeschool to read to your kids — all my friends who send their children to school like normal people read to their children on a regular basis — but I found it easy to commit to a lifestyle that involved wearing pajamas after noon, eating dinner surrounded by stacks of curriculum, and lots of snuggling on comfy chairs. And, just like I’d imagined it, we have plenty of time for the intersection of my two favorite things in the world: my kids and books. It’s not a surprise that our days revolve around reading aloud.

We begin each homeschool day with Mom’s readaloud, a tradition that grew out of our daily struggle to get everyone up and out of bed for lessons. The prospect of math wasn’t very motivating first thing in the morning, but now we ease into our day with about 20 minutes of reading aloud. I get to pick the book, so I can sneak in those personal favorites that the kids have not quite gotten around to reading. (This is how I made sure my teenage son didn’t miss out on Little Women.) When we read The Neverending Story by Michael Ende, I found an edition just like the one I checked out from my local library 30 years ago, printed in green ink for the story of young Atreyu and his friend, Falkor the luckdragon, and their quest to save Fantastia, and in red ink for Bastian, who is reading Atreyu’s story and gradually discovering that he may be part of the adventure. I’m sure my library also had a copy of Elizabeth Enright’s The Saturdays, the first book in the Melendy Quartet, but somehow I never discovered it, so my children and I were introduced together to the four Melendy siblings, growing up in pre-World War II New York and pooling their money to create the Independent Saturday Afternoon Adventure Club.

Another new acquaintance was Fern Drudger, modern day heroine of N.E. Bode’s The Anybodies, who discovers that despite being raised by tragically boring parents (they work for the firm of Beige & Beige and like to collect toasters), she actually belongs to a family with magical powers and a very special house made of books, where lunch is green eggs and ham and Borrowers live in the walls. We so enjoyed Fern (and her narrator, who likes to break into the action to complain about his old writing teacher) that we happily followed her through two sequels, The Nobodies and The Somebodies.

Once we’ve gotten around to math and our other morning lessons, we break for lunch and then gather together again on the couch for homeschool readalouds. We’ve done the same cycle of readalouds with each child, beginning with myths and legends from around the world, and moving on to adaptations of classic literature. It can be difficult to find adaptations that are clear to modern readers without sacrificing too much of the original story, but we always enjoy Geraldine McCaughrean, whose retellings of classic stories (from The Odyssey to One Thousand and One Arabian Nights to The Canterbury Tales and beyond) are witty and detailed. Another favorite retelling of an old story is T.H. White’s version of King Arthur’s childhood, The Sword in the Stone, which combines medieval culture and cheerful anachronism as it describes how Merlin turned the Wart (as Arthur was known) into various animals as part of his education. (T.H. White continues Arthur’s story in the rest of The Once and Future King, of which The Sword in the Stone is the first part, but the tone gets considerably darker and more adult, and I haven’t attempted that as a readaloud.) Towards the end of our readaloud cycle, we spend some time with Shakespeare and the best collection of adaptations I’ve found so far is Leon Garfield’s Shakespeare Stories and its follow-up, Shakespeare Stories II. Garfield also developed Shakespeare: The Animated Tales, a series of BBC-produced 30-minute versions of the plays which are fun and entertaining, along with being good warm-ups for full-length productions.

We end our day with evening readaloud, where each child gets to pick his or her own book. We’ve read everything from the Betsy-Tacy series to The Lord of the Rings, and a while back we spent several months working our way through all of Harry Potter, which involved lots of snuggling in Mom’s large comfy bed (as we don’t quite fit on a chair anymore). It was a lovely full-circle moment, but I’m happy to report that there’s no end in sight to our readaloud journey. I look forward to sharing more of our favorites for reading aloud or reading anytime, and I can’t wait to hear about yours. Happy reading!

Unit Study: Exploring the French Revolution

By the time the French Revolution ended, the class and political landscapes of the Old World has been completely redrawn to value democratic political participation and individual rights. All of this makes it a particularly fascinating period of history to dig into with your high schooler.

The rise of the proletariat launched the bloody end of the Old World and the beginning of a new one, and most people date the revolution’s official beginning to the opening of the Estates General, on May 5, 1789.

The French Revolution was the 18th century revolution that mattered. Across the Atlantic, the revolt of Britain’s colonies raised a few eyebrows, but it was the revolution in France that reshaped the European world. When the revolution began, Europe was dominated by virtually impenetrable class structures and wealthy aristocrats; by the time the French Revolution ended, the class and political landscapes of the Old World has been completely redrawn to value democratic political participation and individual rights. All of this makes it a particularly fascinating period of history to dig into with your high schooler.

SET THE STAGE

To appreciate the impact of (and motivation for) the French Revolution, you need to understand the world that preceded it. A big piece of that world is the pre-Enlightenment notion of royalty, captured in candy-colored opulence in the film Marie Antoinette. As you watch it, talk about the expectations of royalty: They really believed they ruled because some divine being wanted them to and had no problem living the high life regardless of the conditions in which their citizens were living. Were they evil or just completely oblivious? You can decide for yourself. And then you can watch 1938’s La Marseillaise to see the beginnings of this world’s unravelling.

CONSIDER THE SCOPE

Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities carries the reader from the first rumblings of the French Revolution to its bloody, battered climax through the story of two lookalikes who find themselves at the center of revolutionary action. As you read, think about how the revolutionaries are perceived — and how their aims and actions change over the course of the story. How do passion-fueled individuals become a violent mob?

For a non-fiction take, Alexis de Tocqueville’s The Ancien Régime and the Revolution isn’t a contemporary account (Tocqueville was born in 1805), but it’s a near-contemporary look at both the promise of democracy and the failures of democracy leading up to and in the wake of the French Revolution. As you read, think about what interests Tocqueville so soon after the revolution: How did this happen?

Finally, pick up The New Regime by Isser Woloch — it’s a bit staid, but it does a great job chronicling the Revolution’s major, world-changing effects (for better and worse). Divorce, universal education, revised penal codes — as you read, make a list of all the things we now take for granted that originated with the French Revolution.

GET PERSONAL

Once you’ve got a handle on the story of the Revolution, slow down and explore its impact on individual lives. You’ll probably have to read the subtitles, but the French film Danton, depicting the last weeks of Revolution hero-turned-public enemy number one Georges Danton, offers a meaningful look at the dark side of the Revolution (with a bonus commentary on late 20th century Poland). Think about the nature of betrayal in a world of shifting allegiances and power. Get outside of Paris with Daphne du Maurier’s The Glass Blowers, which focuses on the brutal royalist counter-revolution in the 1790s. The Broussard family (based on du Maurier’s real-life ancestors) are caught up in the prospect of revolutionary changes but find it hard to adjust to post-war hardships.

6 Ways to Use Journals in Your Homeschool

Journals can help make writing part of your routine, build analysis skills, add a spine to special studies, and otherwise give your homeschool a surprising boost.

Journals can help make writing part of your routine, build analysis skills, add a spine to special studies, and otherwise give your homeschool a surprising boost.

Journaling is old stalwart of school literature classes — such a stalwart that many homeschoolers dismiss it out of hand, remembering boring afternoons of trying to fill up three pages about nothing in particular. Journals deserve a better reputation, though. Used properly, journals can help students develop confidence, not just as writers, but as thinkers and learners — and not just in literature classes, but across the curriculum.

“Journal writing is a way to personalize every aspect of your curriculum,” says a spokesperson for the research team at Saint Xavier University. “Ultimately a journal is a record of a student’s travels through the academic world.”

Want to make journaling part of your homeschool? Think of these suggestions as a sampler platter of opportunities: Feel free to try the ideas that seem right for your particular student, ignore the ones that don’t, and make all the adjustments that you know work for you. Experiment to figure out how journals work best for your student, and keep experimenting so that your methods grow and develop with your student. Like everything about homeschooling, journaling isn’t a “right-way” kind of activity but one that adapts to the particular learners you have.

Journaling works well as a low-tech investment: Though the idea of a big, fat journal full of empty pages may seem inspiring, some writers tend do better with very small, fill-up-able journals that need frequent replacement. Experiment with different sizes to figure out which is the best fit for your child — you may find that different sizes suit different purposes. (Happily journals can be fairly cheap!) Studies show that students do best if they get meaningful feedback on journal entries — but also that journals are less stressful when students know they’re private. Compromise by asking students to choose which entries you read.

1. Use a journal to encourage everyday writing

The more you write, the more your writing improves — especially if you have a space where writing is all about expressing your own ideas and thoughts and not about producing a final product that’s going to be evaluated critically.

“Journaling helps students make connections between what is really important to them, their curriculum, and their world,” says Kay Burke, author of How to Assess Authentic Learning. Some students may have lots of ideas about what they want to write, but for students new to journaling, a prompt can help a lot with getting started. One fun way to generate topics is to use a MadLibs approach: Brainstorm a list of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, and write them on strips of colored paper — blue for nouns, yellow for verbs, etc. Then, draw words to fill in the blanks of a simple sentence: A/an (adjective) (noun) (verb). Tack on a prepositional phrase — before breakfast, in springtime, at the zoo — to connect to something relevant to your child’s current life. Set a 9-minute timer, and let the writing begin.

Tip: This kind of journaling can be most effective if you do it, too.

2. Use a journal to build analysis skills

Think of two-column journaling as annotating with hand-holding: By literally drawing a line between the text and your own ideas, you’re encouraging students to engage directly with what they’re reading. For newbies or really challenging texts, you may want to keep it simple and ask students to simply summarize as they go, but as you get more comfortable, you can track things like themes and symbolism across readings. You can copy passages into a journal, but students can also treat this like a kind of advanced annotation and write directly in the books they’re reading. This kind of journaling works best when you’re writing right beside the text you’re writing about.

“Students make these connections all the time, but two-column journals push them to articulate and defend those connections,” says Burke. It’s often useful to steer new journal-ers toward one specific idea at a time — look for symbols of hope, or focus on this particular character — so that the possibilities don’t get overwhelming.

For new students, this can mean picking out short passages for them to start with. It’s easy to print a paragraph, clip or tape it inside your journal, and write on the opposite page. If your student is having trouble identifying passages to write about, you can prep a few for them to choose from so that it’s easy to get started. Sometimes it can feel like doing part of the “deciding what to write about” part for your student is too much handholding, but if the writing is the point, make it easy for them to get to that part. You can focus on identifying important passages another time if you want to focus on that skill. One of my big homeschool lessons has been that you’re much more likely to feel successful if you keep your focus on one thing at a time.

Tip: Start with a short poem, and give each line its own page.

3. Use a journal to encourage deeper thinking

When students are ready to move beyond summarizing what they’ve learned, it’s time to dive into the world of asking big questions. For some kids this comes naturally, but other students need a little more guidance, and journaling can provide a useful framework.

Ask students to jot down three questions they have after every new chunk of learning — it might be a chapter of a novel, a podcast about the Norman invasion, or a new math concept. Help students figure out if their questions are informational — are they clarifying something? — or theoretical — are they considering how ideas, implications, and assumptions extend beyond the text? Over time, students will have more and more theoretical questions and become better at recognizing where information gaps manifest in their learning, two things that push deeper thinking.

I talk more about how to encourage kids to ask questions using the Good Thinkers Toolkit in episode 4 of the Thinky Homeschool podcast. (link to the HSL Patreon)

Tip: This journal technique works best if you use it consistently.

4. Use a journal to support self-evaluation

Journaling can also be an effective way to encourage students to evaluate their own work. It may help to have a list of questions for students to work from: What was the most interesting thing about this assignment? How much effort did you put into it? Are you pleased with your results? What do you think is the best part of this project? If you’d had another two hours to work on it, what would you have done? Asking students to write a journal entry at the end of major papers and projects can give you meaningful insight into their thought process, effort, and achievement, says Art Young, editor of Language Connections: Writing and Reading Across the Curriculum.

Figuring out how to evaluate student progress can be tricky for homeschoolers, but kids get a lot of benefit out of assessing their own growth. Taking time to do this not only helps students see where they can improve in the future (thoughtful people will always be able to find something to improve), it also helps them identify places they’ve improved from the past, boosting their overall academic confidence.

Tip: Ask students to submit a journal with every big assignment.

5. Use a journal to add rigor to rabbit trails

One of the great things about homeschooling is being able to follow where our child’s interests lead, but it’s not always easy to figure out how these rabbit trails fit into your curriculum. Sometimes, that’s just fine — after all, everything you study doesn’t have to be about your transcript — but sometimes, a rabbit trail becomes a passion that you want to keep a record of. Journaling makes a lot of sense here — it’s low-effort, but provides a useful history should you need it.

Every week — or as often as seems appropriate — ask your child to jot down what they’ve learned or wondered or been inspired by in their chosen area of interest. You might end up with pages about Minecraft mods or records of kitchen experiments. Over time, kids may come back to certain topics over and over again — when you’re stuck trying to figure out a topic for a history project, flipping back through these journals reminds kids what gets them excited. Maybe they’ll be inspired to build a Roman village in Minecraft or to write a medieval cookbook.

6. Use a journal to spur discussion

One of the best ways to learn about literature is to talk about it with someone else, and for homeschoolers doing their curriculum at home, that someone else is likely to be you. How do you help your student get beyond plot summary and generalizations to deeper discussion? The micro-journal is one effective approach.

After you read something or cover a new topic together, take 5 minutes to jot down your big ideas and questions on an index card. (Stick to a small writing surface so that it feels easy to fill up with ideas.) Don’t worry about complete sentences or perfect phrasing — focus on getting down as much as you can. If it helps your student to have a focus, concentrate on connecting themes to other literary elements, like plot, character, or setting — that’s loose enough to include lots of ideas, but it gives thinkers a place to start. This on-the-fly brainstorming will help student push past their initial impressions so they can dig into material in a less superficial way.

Tip: It may help students if you ask a directing question before you begin brainstorming.

Secular Curriculum Review: IEW’s Student Writing Intensive

IEW’s Student Writing Intensive is a practical, step-by-step writing curriculum that works great for kids who think they hate writing.

IEW’s Student Writing Intensive is a practical, step-by-step writing curriculum that works great for kids who think they hate writing.

When my husband and I decided to homeschool our children, I thought writing would be a cinch to teach. I still think it would be, if I had a kid who was like me when I was a child — a child who was always writing. Growing up, I wanted to write poetry, stories, novels, you name it. And I never balked at a writing assignment.

Many people say that the secret to getting kids to write is to let them write whatever they want, and you can even take dictation for them, if you want. I think that’s good advice for a lot of kids, but my son is different. He doesn’t have any interest in writing anything. If I told him to write whatever he wanted, that would cause him anxiety and not make writing fun.

For a long time I wondered how I could teach him good writing skills without making him hate writing. This is something that I’ll be thinking about every year — how to move forward in a way that’s right for him. Fortunately, this year, I found something to get started with that’s working well. It’s the Institute for Excellence in Writing’s Student Writing Intensive Level A, which is for 3rd-5th graders. Levels B and C are available for higher grades. (Note that you can pair this with their Teaching Writing: Structure and Style, which is a 14-hour DVD Seminar for teachers and much more comprehensive. However, for the sake of this review, I’m writing about the Writing Intensive as a stand-alone curriculum.)

I’ll tell you right up front that I would not recommend this curriculum, if you have a child who enjoys writing. While all kids might benefit and learn something from it, I think it is especially made for kids who don’t have any idea what to write about or how to get started. I’m about halfway through the curriculum with my son right now.

It comes with a set of DVDs, and your child can watch the videos as if he’s sitting there in the classroom, listening to the teacher explain the concepts to a group of students. It begins by teaching students how to create a keyword outline for a paragraph that’s included in the lesson. Basically, he has to pick the three most important words in each sentence. Next, using this outline, he’ll write his own paragraph without looking at the original one. This has taken away the angst of “what am I supposed to write?” that was the first hurdle my son needed to get over.

Subsequent lessons are similar. All the lessons provide a pre-written text to create an outline with, but they add in “dress-ups” that the student needs to include in their paragraphs. Some of the dress-ups include a who/which clause, a strong verb, quality adjective, a because clause, etc. It’s slowly building a toolbox of writing mechanics that will help a child make her writing more varied and interesting. After doing these exercises with short, non-fiction paragraphs, it moves on to longer short stories and teaches students how to write a Story Sequence Chart. I can see where after doing these exercises with pre-written texts and re-writing them in his own words, my son may gain confidence in his writing ability and this will later free him up to begin some of his own, original writing. So far, I’ve been happy with it.

However, I have a few, small issues with this curriculum. First of all, some of the paragraphs he’s been using at the beginning of this curriculum should be proofread a little more closely. I have found more than one poorly written sentence. I always tell my son what is wrong with it, but for a parent who doesn’t have strong writing skills, I see this could be a problem. I feel a writing curriculum should offer excellent writing examples, though I also tell my son that this gives him a chance to write the paragraph better.

I also have a problem with forcing the student to use one of each dress-up in their paragraph. While I see the benefit of repetition so that the student becomes more comfortable with the using these sentence structures, and I love how it reinforces grammar skills, forcing every dress-up does not always make the best writing, especially in a short paragraph.

I have dealt with this issue by explaining to my son the purpose of these exercises. I told him that his writing will sound better if he varies the length and type of his sentences. He should try his best to use the dress-ups, but if they don’t serve the writing by making it sound better, he doesn’t have to do it. I go over his work with him, and I make suggestions, if I see a way to do it, but I don’t make him, for example, include a who/which clause into his writing, if I feel what he wrote without one is good writing.

This Student Writing Intensive offers some tips for kids that have been great for my son as well. The first one is that he’s only allowed to write with a pen. This takes away the urge to stop and erase and make the writing perfect the first time. The rough draft does not need to be perfect, and he’s learning proofreading marks to make corrections. The other tip that this curriculum offers is that a parent should be a walking dictionary for the child, telling him how to spell any word he doesn’t know. This takes a lot of angst out of writing that first draft too.

Overall, I like how this curriculum is helping my son put words on paper in a way that is not making him hate writing. It is a very formal program, which doesn’t work for every child, but if you have a child who has no interest in putting words on paper and/or likes having a “toolbox” to work with, it might be worth looking at.

If you use one of the Student Writing Intensives, IEW also offers continuation courses. I’m not sure whether that will be the right next step for my son, however. We’ll see when we get there.

Unit Study: Queen Victoria

You could spend years digging into the life of the British ruler who gave the Victorian age its name and still make new discoveries, but consider these resources a delightful starting point for a high school history homeschool unit study.

Celebrate Victoria Day on May 22 by learning more about the British queen it’s named for.

When Alexandrina Victoria took the throne of England in 1837, she was a teenager inheriting a seriously tainted monarchy. By the time of her death in 1901, the Queen had become a global symbol of the British Empire, the time period had become eponymous with her name, and she would successfully redefine royalty for the modern world. Some of this was luck, some of this was the people who surrounded her, and some of it was the sheer stubborn determination of Victoria herself. You could spend years digging into Victoria’s life and still make new discoveries about the 19th century queen, but consider these resources a delightful starting point.

READ

Who Was Queen Victoria? BY JIM GIGLIOTTI

This is a predictably solid entry in the reliable Who Was elementary biography series, covering Victoria’s life from unhappy childhood to triumphant Jubilees. (Elementary)

My Name Is Victoria BY LUCY WORSLEY

Worsley imagines Victoria’s life through the eyes of her forced companion, John Conroy’s daughter — also named Victoria — who is brought to Kensington Palace to spy on the Queen-to-be but finds herself sympathetic instead. (Elementary)

Victoria: May Blossom of Britannia, England, 1829 BY ANNA KIRWAN

This historical fiction novel is part of the Royal Diaries series, so its focus is on Victoria’s unhappy princess period, when she dreams of being Queen as a way to escape her miserable life at Kensington Palace. (Middle grades)

Victoria Victorious BY JEAN PLAIDY

Jean Plaidy is less sparkly than usual in this historical novel, and like so many writers, she dwells on the romance of the early half of Victoria’s reign, when she is a young queen in love with her husband, but this first-person story is a thoughtfully researched introduction to Queen Victoria’s life. (Middle grades)

Queen Victoria BY LYTTON STRACHEY

For the post-World War I view of Queen Victoria, turn to Lytton Strachey’s very un-Victorian biography, a classic, snarky history as full of royal gossip as historical details. (High school)

Victoria BY DAISY GOODWIN

This YA-friendly historical fiction biography focuses on Queen Victoria’s first two years as Queen of the British Empire, bringing to life the larger-than-life personalties who defined the early years of her reign, including the very charismatic prime minister Lord Melbourne, Victoria’s cousin (and future husband) Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Victoria herself. (High school)

Victoria: The Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire BY JULIA BAIRD

If you’d like a frothy biography that reads like a well-researched version of “Keeping Up with the Hanovers,” pick this up: Baird writes a little like a romance novelist and holds firm to her theory that Victoria secretly married her servant John Brown, but it’s a fun read. (High school)

We Two: Victoria and Albert: Rulers, Partners, Rivals BY GILLIAN GILL

Even though Victoria reigned for half her life without Albert, his influence on her was so great that he permanently shaped her ideas (for better and worse) about what a monarch, a parent, and a woman should be. This dual biography illuminates the most important relationship of Victoria’s life and the constant tension between power and family love that it inspired. (High school)

Victoria’s Daughters BY JERROLD M. PACKARD

It was not easy to be the offspring of the ruler of the British Empire and her perfectionist partner, and this group biography explores the lives of the five women who called Queen Victoria mother. It’s a sad and fascinating history of female life on top tier of British society, with a special interest in the life of rebellious Princess Louise. (High school)

Uncrowned King: The Life of Prince Albert BY STANLEY WEINTRAUB

I’m always telling my students that had Albert lived as long as his wife, we would probably be calling the 19th century the Albertine Era. Weintraub does a great job painting a vivid picture of the reform-minded, ethically intense polymath who proved the perfect romantic and political partner for the woman he was steered to marry since childhood. (High school)

The Letters of Queen Victoria BY QUEEN VICTORIA

One of the best ways to get to know someone is through her own words, and Victoria is no exception. The Letters of Queen Victoria put the Queen’s best foot forward, clearly demonstrating how the chief figure of the Victorian era wanted to be seen by the people in her world. (And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that her children re-edited these letters, too.) (High school)

WATCH

Victoria

Jenna Coleman’s Victoria is neither prim nor proper, but she’s certainly interesting in this fairly faithful BBC adaptation created by Daisy Goodwin. OK, it veers a little toward the romantic with heartthrobs cast as middle-aged Melbourne, aristocratic Albert, et al, but who are we to complain about a little eye candy in period costume?

The Young Victoria

Emily Blunt is the lonely little girl crowned Queen of England in this dreamy biopic focused on the years 1836 to1840. Paul Bettany is a particularly disreputable Lord Melbourne, Mark Strong is a particularly vile John Conroy, and Miranda Richardson is a conflicted Duchess of Kent, but Blunt steals the show with her Victoria torn between the desire for freedom and independence and longing for a real family.

Victoria the Great

This 1937 film focuses on the early years of Victoria’s reign. The film, commissioned by Edward VII in honor of his great-grandmother, includes sets and costumes that are accurate reproductions of actual items in the British museum.

Mrs. Brown

Judi Dench is glorious as a middle-aged Victoria who cannot seem to get her Queenly groove back after the death of Prince Albert. Only Albert’s Highland servant, John Brown, cheers her up, but friendship between a Queen and a rowdy Scotsman seems pretty scandalous.

Victoria and Abdul

Judi Dench reprises her role as Victoria in another historical account of the Queen’s fondness for her servants: This time, it’s focused on Victoria’s late-in-life friendship with her Indian servant Abdul Karim.

Ohm Krüger

For a totally different perspective, screen this World War II German propaganda flick about the Boer War, which paints Queen Victoria as a ruthless alcoholic who tricks the Germans into signing an unfair treaty.

PBS Empires: Queen Victoria

This series focuses on the politics and geography of the Victorian empire, which ruled one-fifth of the world’s people during Victoria’s 64 years on the throne.

6 Tips to Wrap Up Your Homeschool Year

Get your end-of-the-year record-keeping and organizing done so you can enjoy some time off.

Get your end-of-the-year record-keeping and organizing done so you can enjoy some time off.

It’s May and I’ve lost my mojo. I even doubled my caffeine intake to no avail.

It seems most every homeschooling parent gets to a point when they need to wrap up their school year. Even those parents that homeschool year-round, feel the pull of spring in May; the need to be done.

Homeschooling parents can quickly be overcome with the amount of material that’s accumulated throughout a long and creative homeschool year. Wrapping up the year can seem overwhelming. Here are some tips to get that clutter off your kitchen counter and put the homeschooling year to bed.

1. File end of year paperwork.

Be sure to file any end of year paperwork required in your district. Evaluations, portfolios, or other measures of progress, as well as letters of intent to homeschool, may be due now. Spend some time and get those out of the way so you can enjoy the summer days.

2. Update transcripts/report cards and evaluations.

Don’t wait for months to finalize report cards or evaluations. You will want to complete this task while the information is fresh in your mind. Tracking courses and progress is especially important if you are creating a transcript for your high schooler. Grades, field trips, courses, online classes, community groups, service projects, lab work, job experience, internships, apprenticeships, extracurricululars; all are easily lost or forgotten if not immediately recorded. Unschoolers should also record any classes, experiences or community involvement for their portfolio or transcript.

Unit studies can be easily put away in file folders labeled with the year or grade of the child.

If your child has completed a class through another organization, be sure to gather certificates of completion or grades from the teacher, if that is offered as part of the class.

Kids' school work can also be saved digitally. Take a photos and file in a folder for your portfolio or create a scrapbook of your incredible year. Grandparents especially love thumbing through scrapbooks and sharing memories with their grandchildren. Scrapbooks are also a great way to deter naysayers who might think your kids sat around eating Cheetos all year long.

3. Toss the rubbish.

What do you do with the hordes of paperwork that have accumulated? If your children are in their elementary years, save a few special pieces of artwork and toss the rest. The craft stores have pizza-style boxes that you can buy which are great for storing both artwork and academic work. The pizza boxes stack and store easily on a shelf, don’t take up much room, and hold a lot of material. Save one or two papers each month from each subject and toss the rest. I usually save one paper that shows beginning skills and one that shows mastery. My district/state doesn’t require evaluations of our work but I do save the boxes for three years and then get rid of them.

If you have many 3D sculptures, dioramas, hanging mobiles, and the like for art projects, it can be tougher to part with these masterpieces. Gifting the grandparents or aunts and uncles is a great way to share your homeschooling days with relatives. We always told our kids that if it didn’t fit in the storage box, we could not keep it. Certainly, a few special pieces were kept but the majority went into the box or were gifted away.

4. Clean up the extras.

Dump the moldy bread science experiment that’s been sitting on your shelf for weeks. Organize your homeschool space if you have one, clean off the desks, put the glue sticks and crayons back in their holders, give everything a good spring-time scrub down.

5. Label and store books.

I have a filing system for all of my books. At one point, I was homeschooling three kids in three different grade levels. The number of books, texts, instruction manuals, and other material accumulated through the years, was astounding. Before you pack everything up for the year, label the inside of every single book with an approximate grade level. Include chapter books, workbooks, and manipulatives in this process. I also place grade level stickers on the spines, so that when I store them, I can easily pull the next grade level I need for the coming year. Having organized books has been a lifesaver on so many occasions.

Donate, sell, or trade any items that you won’t use again. As my kids aged up through grades, I save curricula that was going to be used again. Any grade level items that we’d no longer use were donated or sold.

6. Plan some fun activities to celebrate

Get out of the house by planning some time with friends to celebrate the great weather. A picnic in the park, care-free playground days, lunch out with the kids, or a field trip can give you some much needed energy to push through those last few weeks of homeschooling.

Be proud of all your kids have accomplished this year. Don’t worry about the small things that didn’t get completed. Your children have likely learned so much exploring their own love of learning. Enjoy these last days and finish strong!

6 Must-Visit National Parks for Homeschoolers

It’s the ultimate homeschool field trip! Plan a learning and outdoor adventure to one of the U.S. National Parks this summer. (And of course we have a book recommendation for every park!)

It’s the ultimate homeschool field trip: Plan a learning and outdoor adventure to one of these great U.S. National Parks this summer. (And of course we have a book recommendation for every park!)

PHOTO: National Park Service

When the United States first set aside the land that would become Yosemite National Park as protected wilderness during the Civil War, it was doing something brand-new. For the first time, a country was valuing wild-ness over development — and using its own legislative system to do it.

In a way, this made perfect sense: The United States didn’t have the centuries-old cathedrals and castles Europe did. What it did have was a continent full of natural wonders: mountains, geysers, prairies, mesas, beaches, forests. (It was also, of course, a continent full of independent nations and cities that had existed long before European colonizers — when artist George Caitlin first suggested the idea of a “nation’s park” in 1832, his idea was as much to protect Native Americans and their way of life as it was to protect the west’s wildlife and wild spaces.) More than century later, thanks to the efforts of committed conservationists like John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt, the United States parks system includes 392 national parks, monuments, battlefields, seashores, recreation areas, and other protected spaces. All of them are worth a visit — the writer Wallace Stegner called the United States’ national parks system “the best idea we ever had” — but these six should absolutely be on your homeschool bucket list.

1. Yellowstone

First established: 1872

Yellowstone was the first national park, due in large part to privately funded expeditions that reported geological and natural marvels like exploding geysers, alpine lakes, and roaming bison.

Why you should go this summer: Late spring is baby animal season at Yellowstone, so summer visitors might spot wolf pups, little pronghorns, or elk and bison calves roaming the park with their parents. (Take one of the park’s Xanterra tours to improve your wildlife-spotting chances.) Join the crowd to wait for Old Faithful geyser to erupt — it’s one of the rare experiences that feels totally worth the wait-time. Check out the spectacularly hued rainbow geology of the Grand Prismatic Hot Spring. Take a paddling trip to explore Yellowstone Lake, and bring your binoculars to keep an eye out for birds and wildlife.

Recommended reading: Letters from Yellowstone by Diane Smith

National Park Service Photo by David Quinn

2. Grand Canyon National Park

First established: 1919

“The Grand Canyon fills me with awe,” said Theodore Roosevelt, who believed the geological wonder was the one sight every U.S. citizen should see. “It is beyond comparison — beyond description; absolutely unparalleled throughout the wide world.”

Why you should go this summer: Though things get crowded in summer, by the end of August and into September, the park quiets back down. If you’re visiting in the busy season, get a more private view by walking the level, wooded trail to Shoshone Point — since it’s not accessible by car, this lookout point gets significantly fewer visitors. The 3-mile Kaibab Trail to Cedar Ridge delivers the most bang for your hiking buck, with great views and beginner-friendly terrain.

Recommended reading: Carving Grand Canyon: Evidence, Theories, and Mystery by Wayne Ranney

3. Great Smoky Mountains National Park

First established: 1934

Great Smoky Mountains National Park attracts the most visitors of any national park — more than 10 million in 2015 alone. (That’s more than twice as many visitors as the second-most popular park received.)

Why you should go this summer: June and July are the park’s busiest seasons, but August and September are much quieter — and warm days, a plethora of summer wildflowers, and lots of young wildlife make these months a magical time to visit the park. Greet the sunrise at Cades Cove, where the misty valley will help you appreciate the “smoky” name and the waking-up wildlife is often out and about. This is one park where being an early bird is a smart move. (You can always declare an early bedtime.) Walk up to the observation tower at Clingmans Dome to get a panoramic view of the Appalachian mountains.

Recommended reading: Bear in the Back Seat: Adventures of a Wildlife Ranger in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park by Carolyn Jourdan

4. Rocky Mountain National Park

First established: 1915