6 Must-Visit National Parks for Homeschoolers

It’s the ultimate homeschool field trip! Plan a learning and outdoor adventure to one of the U.S. National Parks this summer. (And of course we have a book recommendation for every park!)

It’s the ultimate homeschool field trip: Plan a learning and outdoor adventure to one of these great U.S. National Parks this summer. (And of course we have a book recommendation for every park!)

PHOTO: National Park Service

When the United States first set aside the land that would become Yosemite National Park as protected wilderness during the Civil War, it was doing something brand-new. For the first time, a country was valuing wild-ness over development — and using its own legislative system to do it.

In a way, this made perfect sense: The United States didn’t have the centuries-old cathedrals and castles Europe did. What it did have was a continent full of natural wonders: mountains, geysers, prairies, mesas, beaches, forests. (It was also, of course, a continent full of independent nations and cities that had existed long before European colonizers — when artist George Caitlin first suggested the idea of a “nation’s park” in 1832, his idea was as much to protect Native Americans and their way of life as it was to protect the west’s wildlife and wild spaces.) More than century later, thanks to the efforts of committed conservationists like John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt, the United States parks system includes 392 national parks, monuments, battlefields, seashores, recreation areas, and other protected spaces. All of them are worth a visit — the writer Wallace Stegner called the United States’ national parks system “the best idea we ever had” — but these six should absolutely be on your homeschool bucket list.

1. Yellowstone

First established: 1872

Yellowstone was the first national park, due in large part to privately funded expeditions that reported geological and natural marvels like exploding geysers, alpine lakes, and roaming bison.

Why you should go this summer: Late spring is baby animal season at Yellowstone, so summer visitors might spot wolf pups, little pronghorns, or elk and bison calves roaming the park with their parents. (Take one of the park’s Xanterra tours to improve your wildlife-spotting chances.) Join the crowd to wait for Old Faithful geyser to erupt — it’s one of the rare experiences that feels totally worth the wait-time. Check out the spectacularly hued rainbow geology of the Grand Prismatic Hot Spring. Take a paddling trip to explore Yellowstone Lake, and bring your binoculars to keep an eye out for birds and wildlife.

Recommended reading: Letters from Yellowstone by Diane Smith

National Park Service Photo by David Quinn

2. Grand Canyon National Park

First established: 1919

“The Grand Canyon fills me with awe,” said Theodore Roosevelt, who believed the geological wonder was the one sight every U.S. citizen should see. “It is beyond comparison — beyond description; absolutely unparalleled throughout the wide world.”

Why you should go this summer: Though things get crowded in summer, by the end of August and into September, the park quiets back down. If you’re visiting in the busy season, get a more private view by walking the level, wooded trail to Shoshone Point — since it’s not accessible by car, this lookout point gets significantly fewer visitors. The 3-mile Kaibab Trail to Cedar Ridge delivers the most bang for your hiking buck, with great views and beginner-friendly terrain.

Recommended reading: Carving Grand Canyon: Evidence, Theories, and Mystery by Wayne Ranney

3. Great Smoky Mountains National Park

First established: 1934

Great Smoky Mountains National Park attracts the most visitors of any national park — more than 10 million in 2015 alone. (That’s more than twice as many visitors as the second-most popular park received.)

Why you should go this summer: June and July are the park’s busiest seasons, but August and September are much quieter — and warm days, a plethora of summer wildflowers, and lots of young wildlife make these months a magical time to visit the park. Greet the sunrise at Cades Cove, where the misty valley will help you appreciate the “smoky” name and the waking-up wildlife is often out and about. This is one park where being an early bird is a smart move. (You can always declare an early bedtime.) Walk up to the observation tower at Clingmans Dome to get a panoramic view of the Appalachian mountains.

Recommended reading: Bear in the Back Seat: Adventures of a Wildlife Ranger in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park by Carolyn Jourdan

4. Rocky Mountain National Park

First established: 1915

It’s easy to get your Rocky Mountain high at this park, where visitors can go from sea level to 12,183 feet at the park’s highest point. It took a lot of pressure from local nature lovers to protect this park, which miners, loggers, and other developers had their eye on during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Why you should go this summer: September, when the elk move to lower elevations in search of mates and the tundra turns crimson, is one of the most picturesque times to visit. The sheer variety of ecosystems in this park is staggering, and you can explore them all in the summer: wetlands, pine forested woodlands, montane areas, and alpine tundras stud the mountainous landscape, waiting to be discovered. Stand in the middle of the continental divide, and watch the water on one side head toward the Atlantic Ocean while the other side flows toward the Pacific.

Recommended reading: A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains by Isabella Lucy Bird

President Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir standing on rock at Glacier Point, Yosemite, May 1903; Yosemite Falls and cliffs of Yosemite Valley in distance.

5. Yosemite National Park

First established: 1890

“No temple made with human hands can compete with Yosemite,” wrote John Muir, whose conservationist crusading helped this California wilderness become one of the country’s first established national parks.

Why you should go this summer: By June, the entire park is open to visitors, which gives you an all-access pass to explore the park, including the many run-off waterfalls that peak in the spring and early summer. (By August, many have dried out for the season.) Rent a raft to float down the Merced River, a seasonal activity that can provide top-notch wildlife viewing. Wild- flowers come late to the park’s higher elevations, which means you can enjoy fields of wildflowers well into the summer. Though lots of people take advantage of the summer fun at this park, Cascade Creek is almost never crowded and makes a great spot for free play and nature exploration.

Recommended reading: The Camping Trip That Changed America by Barb Rosenstock

6. Acadia National Park

First established: 1916

The mountains meet the sea at this oldest national park east of the Mississippi. Acadia was originally named Lafayette National Park, for America’s favorite fighting Frenchman, but its name was changed to Acadia, in honor of the area’s original French settlement, in the 1920s.

Why you should go this summer: Museums and the nature center are open, tours are plentiful, and special events like concerts and plays occur during the summer months in Acadia. It’s also — barely — warm enough to take a dip at Sand Beach, home to some of Maine’s coldest water temperatures. Rent bikes to explore the carriage roads that criss-cross the park.

Recommended reading: Beckoning Landfall by Eric Berry

Homeschool Unit Study: The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

The U.S. Civil War was a bloody, bitter conflict about slavery that continues to influence our national consciousness. There’s no shortage of resources for studying the Civil War out there, but these are some of our favorites.

Books

Albert Marrin’s Civil War trilogy — Commander in Chief: Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, Unconditional Surrender: U.S. Grant and the Civil War, and Virginia’s General: Robert E. Lee and the Civil War (though this one is a little more apologist for Lee than I prefer)— makes a great read aloud spine for your Civil War studies if you are interested in the war part of the Civil War. Marrin does an excellent job illuminating the personalities and events of the Civil War while still presenting a straightforward, chronological history of the war.

Janis Herber’s The Civil War for Kids: A History with 21 Activities includes hands-on projects like making butternut dye (used by Confederate soldiers on their uniforms), baking hardtack (a food staple for soldiers in the fields), and decoding wigwag (a flag system used to pass messages long distances during the Civil War). This is written for younger students, but I find that high schoolers enjoy a few hands-on activities in their history studies, too.

How can neighbors fight on different sides of the same war? Harold Keith’s Rifles for Watie does a nice job illustrating the complexities of the war through the experiences of fictional Kansas teenager Jefferson Davis Bussey, who finds himself fighting for both the Union and Confederate armies over the course of the war. Keith also focuses his narrative on the war’s western front, which may not be as familiar to younger historians.

The Civil War was the first technology-assisted war, and new weapons, communication devices, and transportation systems played a significant role in the war’s outcome. In Secrets of a Civil War Submarine: Solving the Mysteries of the H. L. Hunley, Sally Walker explores the history of the Confederate submarine that became the first submarine to sink a ship in wartime — though it never resurfaced after the battle. Walker tackles both the science and history of the submarine’s Civil War days and the modern-day forensic work of discovering and investigating the sunken vessel.

Talking about slavery can be one of the hardest parts of studying the Civil War with your kids. Many Thousand Gone: African Americans from Slavery to Freedom by Virginia Hamilton manages to tackle to subject with a rare combination of sensitivity and thoroughness.

When Steve Sheinkin was writing history textbooks, he hated that the most interesting bits always seemed to get left out. He cheerfully remedies that problem in Two Miserable Presidents: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You about the Civil War, an engrossing, anecdote-rich history of the War Between the States that’s equal parts smart and surprising.

Irene Hunt’s Across Five Aprils focuses on life on the homefront. There are no heroic charges or dramatic battles for teenage Jethro Creighton, just the increasingly difficult task of keeping the family farm going while his brothers are away fighting in the Civil War.

In the Shadow of Liberty by Kenneth C. Davis isn’t just about the Civil War — but its collected biographies of Black Americans who were enslaved by former U.S. Presidents illuminate the hypocrisy lurking behind “the land of the free.” This book is an important reminder that talking about the Civil War without talking about how the United States justified, protected, and relied on slavery kind of misses the point.

Paul Fleischman’s Bull Run is a collection of sixteen monologues reflecting the personal experiences of people of different ages, races, genders, and regions during the First Battle of Bull Run.

Soldier’s Heart by Gary Paulsen is not an easy book to read, but this novel about 15-year-old Charley Goddard, who enlists with the First Minnesota Volunteers at the start of the Civil War and who returns home four years later, forever changed by his experiences, is powerful stuff.

Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts by Rebecca Hall is a fascinating graphic novel history of Black women’s leadership in enslaved people’s uprisings. I learned so much reading this book! Similarly, Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s biography She Came to Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman is a brilliant reminder that Black Americans were fighting against slavery before and during the Civil War.

The lasting impact of the Civil War is the central focus of Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. Though it’s more appropriate for older readers, Horowitz’s journey into the legacy of the Confederacy in the modern-day South raises the kinds of questions that can keep you talking for days.

Movies

Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990) is the undisputed must-see Civil War documentary. Though Burns caught some flack from historians for his“American Iliad,” his epic history of the Civil War is rich with details and emotionally charged. Balance it with thoughtful conversations about slavery and Reconstruction.

Glory (1989) tells the story of the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a platoon of African-American soldiers whose assault on Fort Wagner at the Battle of Fort Wagner helped the Union army win that battle. Though the story is exciting enough to be fiction, it’s firmly rooted in real historical details.

Gettysburg (1993) is based on Michael Shaara’s excellent novel The Killer Angels and was filmed on the battlefields of Gettysburg. The film focuses on the 1863 battle that prompted Lincoln’s famous address. (The follow-up film, Gods and Generals, is worth watching, too, if you want more.)

The tear-jerker ending of Shenandoah (1965) softens the film’s anti-war message, but the toll of war off the battlefield remains a major theme. Jimmy Stewart plays a Southern farmer who wants nothing to do with a war that doesn’t concern him — until his family, like so many families, is affected by the violence of the war.

Online Resources

The Valley of the Shadows project chronicles the history of two communities — Franklin County in Pennsylvania and Augusta County, Virginia — through the years leading up to, during, and following the Civil War. Thousands of primary sources tell the story of what life was like for people living through one of the United States’ most turbulent periods.

It would be hard to overemphasize the importance of the railroad in the progress and outcome of the Civil War, and the digital history project Railroads and the Making of Modern America walks you through the railroad’s role in military and political strategy.

The National Park Service’s Civil War hub has lots of information about the War Between the States, but one of the most practical resources for homeschoolers in search of a field trip is the comprehensive list of Civil War landmarks around the country.

One of the most interesting things about the Freedmen and Southern Society Project is its illumination of the role that slaves themselves played in the emancipation process.

Was the Civil War inevitable? See for yourself, as you face the same choices President Lincoln did in Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads, an interactive game developed by the National Constitution Center.

The 1862 battle at Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg) inspired Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. You can trace the pivotal battle online at Antietam on the Web, which includes handy maps and information about participants on both sides of the field.

Sherman’s march to the sea, cutting a swath of destruction through Georgia and effectively cutting off the Confederate Army, may be one of the best-known campaigns of the Civil War — and you can follow General Sherman’s route on the interactive maps at Sherman’s March and America: Mapping Memory.

The lines between North and South weren’t always as simple to draw as history books suggest, and New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War explores New York’s complex place in the war. The city supported a thriving abolitionist movement even as it relied on slavery-supported economic ties to the South.

Field Trip

Appomattox Courthouse National Historical Park has a full schedule of reenactments, lectures, guided battlefield walks, and more to commemorate Lee’s surrender here 150 years ago.

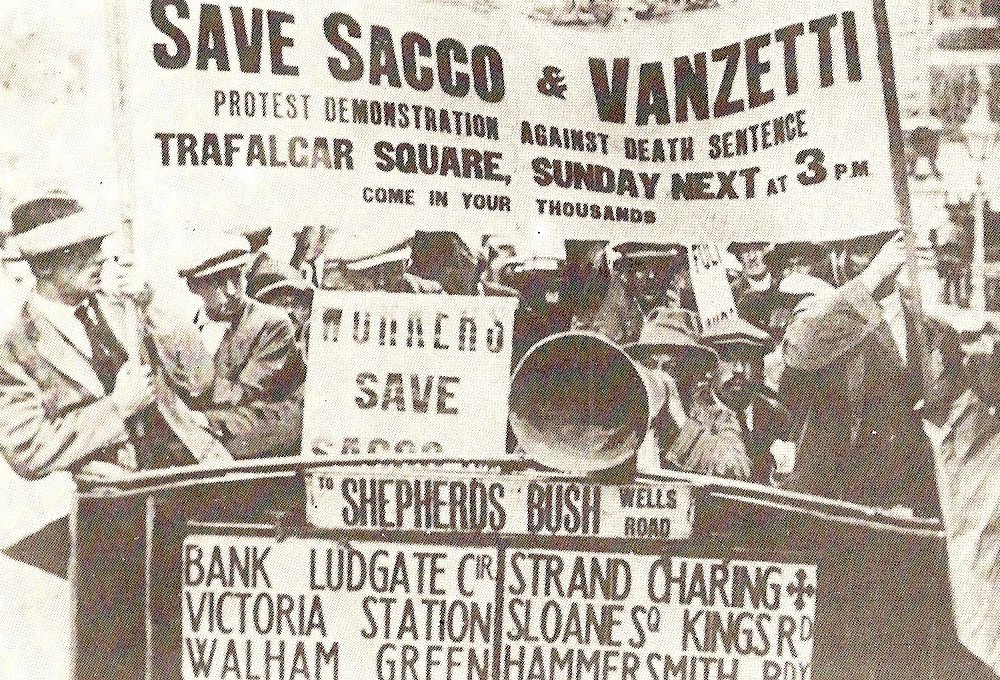

Homeschool Unit Study: The Sacco-Vanzetti Case

One of the most notorious trials of the 20th century United States makes a great starting point for big conversations about racism and the Red Scare.

How impartial is the U.S. justice system really? A deep dive into this notorious 20th century court case gives historical context for that big question.

The Sacco-Vanzetti case, which began in April 1920, remains one of the most controversial and debated cases in U.S. history. Did Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti commit the murder for which they were executed? The answer to that question remains less important than the other questions about immigrants, political opinions, and justice that it continues to raise. This is just one case, but digging into with your high schooler reveals a lot about the United States in the 1920s, anti-immigrant sentiment, and the Red Scare.

The Case:

On April 15, 1920, robbers killed a paymaster and a guard at a shoe factory in South Braintree, Massachusetts before escaping. Suspicion fell on two naturalized Italian immigrants: Nicola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a fish peddler. Sacco and Vanzetti were ideal villains — as atheists, draft avoiders, and anarchists, they represented a triple-threat to American ideas about the importance of religion, country, and property.

The problem was that they might not actually have been villains. Caught up in a maelstrom of prejudice and fear, their case moved rapidly to court and execution, in the end resembling a slow-moving lynch mob as much as an organized pursuit of justice. Neither man had a criminal record, and there was no evidence against them. Another known criminal actually confessed to the crime while the trial was happening. Despite numerous appeals and evidence of the innocence, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed August 23, 1927.

Listen to this: The Past Present: History For Public Radio’s episode on Sacco and Vanzetti includes historical audio of the defendants and other people involved in the case, Woody Guthrie ballads, Italian anarchist songs, and readings from the letters Sacco and Vanzetti wrote from prison. (Scroll to the bottom to download the full program.)

Talking point: Why were anarchists targets for suspicion in the 1920s United States?

Read this: How did people feel about the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti? The New York Times gave them the day’s main headline, and for the first time in modern history, the city of Boston shut down Boston Common in fear that activists would congregate there. The poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, one of many artists who tried to have the verdict overturned, wrote, “[the] men were castaways upon our shore, and we, an ignorant savage tribe, have put them to death because their speech and their manners were different from our own, and because to the untutored mind that which is strange is in its infancy ludicrous, but in its prime evil, dangerous, and to be done away with.’ And the Atlantic Monthly published a long essay by future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter highlighting some of the major problems with the case.

Talking point: How did anti-immigrant sentiment contribute to the sentence in this case? (You may want to look up the immigration quotas of 1924, which passed while Sacco and Vanzetti were in prison.)

Explore this: You can visit the virtual exhibit Sacco & Vanzetti: Justice on Trial from Boston’s John Adams Courthouse online and explore the history and after math of the trial, including court transcripts like this cross-examination of Sacco:

QUESTION: Did you love this country in the last week of May, 1917?

SACCO: That is pretty hard for me to say in one word, Mr. Katzmann

QUESTION: There are two words you can use, Mr. Sacco, yes or no. Which one is it?

SACCO: Yes.

Talking point: Would it have been possible for Sacco and Vanzetti to get a fair trial somewhere else?

Watch this: Tony Shaloub and John Turturro lend their voices to Peter Miller’s 2006 documentary Sacco and Vanzetti, which recreates the trial and incorporates modern forensic evidence.

Movies for Women’s History Month

Celebrate Women’s History Month this March with a homeschool movie marathon.

March is Women’s History Month, and every year, it feels more than ever like a time to think about how far women have come in the modern world — and how far we still have to go. These films will inspire and engage as you explore women’s history.

One Woman, One Vote

Susan Sarandon narrates PBS’s American Experience documentary on women’s rights, a well-rounded and informa- tion-rich introduction to women’s suffrage in the United States. Bonus: This documentary does a really nice job of exploring the role of black women in the suffrage movement.

Iron Jawed Angels

Hillary Swank and Frances O’Connor star in this sometimes weirdly directed but ultimately very compelling story about the U.S. battle for women’s rights. There are some invented historical incidents, but the overall story is rooted in real events.

Nine to Five

Maybe an indictment of women’s treatment in the 1980s workforce shouldn’t be this hilarious, but sometimes laughter really is the best social commentary.

Not for Ourselves Alone

Ken Burns takes on the women’s movement with this documentary focused on the lives of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two of U.S. history’s best known fighters for women’s rights.

The Magdalene Sisters

This film about the Irish institutions where“wayward women” were sent — and often abused — definitely deserves its R rating, so you may want to preview it. But since the last of these institutions didn’t close until the 1990s, it’s a movie worth watching with your older students.

The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter

The women who — more than capably — took on “men’s work” during World War II are the subject and stars of this poignant, powerful documentary.

A Midwife’s Tale

This fascinating documentary explores the life of an 18th century Maine midwife and the 20th century historian who discovered her diary and brought it to light.

14 Women

This sometimes overly earnest but still engaging 2007 documentary focuses on the — wait for it — fourteen female Senators in the 109th United States Congress.

Heaven Will Protect the Working Girl: Immigrant Women in the Turn-of-the-Century City

Before women won the right to vote, immigrant women crusaded for safer and more reasonable work conditions in booming factories and sweatshops. This short documentary illuminates their struggle — and victories.

The Burning Times

Some feminist scholars call the persecution of witches that occurred from the 1400s to the 1700s the “Women’s Holocaust” because of the huge number of women who were executed during this time. This documentary considers the history, causes, and effects of this problematic period in women’s history.

Black Women’s Biographies for Black History Month

In honor of Women’s History Month and Black History Month, we’ve rounded up some history-making Black women who should be better known than they are. Add them to your secular homeschool curriculum in Black History Month and every month.

Get these women in a history book! In honor of Women’s History Month and Black History Month, we’ve rounded up some history-making Black women who should be better known than they are.

Photo: Johnny Silvercloud via Wikimedia Commons

If women get short shrift in history textbooks, black women get doubly short-changed — and that’s a shame, because cool women like these deserve wider recognition. Fortunately, your homeschool can correct the omission, and now’s the perfect time to get to know some of these women a little better.

Ella Baker

“My theory is, strong people don’t need strong leaders,” said civil rights activist Baker, who worked mostly behind the scenes from the 1930s to the 1980s to develop the NAACP, eliminate Jim Crow laws, organize the Freedom Summer, and found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

READ THIS: Lift As You Climb

Elizabeth Keckley

Keckley — who bought her freedom from enslavement in the mid-1800s and started a successful dressmaking business — was Mary Todd Lincoln’s confidante and generated much controversy with her behind-the-scenes book about the Lincolns.

READ THIS: Behind the Scenes

Mary Fields

Six-foot-tall, cigar-smoking, shotgun-toting Mary Fields was born enslaved and became the first Black woman mail carrier in 1895 at age 60 by being the fastest applicant to hitch a team of six horses. She never missed a delivery — when snow was too deep for her horses, she strapped on snowshoes to deliver mail. “Stagecoach Mary” was so beloved that schools closed to celebrate her birthday and the mayor exempted her from Montana’s law against women entering saloons.

READ THIS: Fearless Mary

Ora Washington

Imagine if Serena Williams wrapped up her tennis career by becoming a pro basketball player — then she might considered a modern-day Ora Washington. Despite the racism of the early 20th century sports world — the top white woman player refused to meet Washington in a match — Washington won the American Tennis Association’s singles title eight times in nine years and went on to head up a women’s basketball team that dominated the sport for more than a decade.

READ THIS: Overlooked No More: Ora Washington, Star of Tennis and Basketball

Violette Anderson

Violette Anderson worked as a court reporter for 15 years before becoming the first woman to graduate from law school in Illinois. Her private practice was so successful that she was appointed assistant prosecutor for the city of Chicago. In 1926, she became the first black woman to practice law before the U.S. Supreme Court.

READ THIS: Her Story: A Timeline of Women Who Changed America

Biddy Mason

Bridget Mason, called “Biddy,” moved to California with the Mississippi Mormon family who had enslaved her. Technically, in 1851 California, this made Biddy — and all Smiths’ enslaved workers — free. Biddy took her owners to court to sue for her freedom, succeeding in freeing herself and all the other family slaves. Biddy went on to amass a fortune in Los Angeles real estate, which she used to fund charities, found schools, build churches, start parks, and more.

READ THIS: Biddy Mason Speaks Up

Nina Mae McKinney

It wasn’t easy being one of the first black actresses in a racist United States, but Nina Mae McKinney earned her reputation as “the black Garbo” with stellar performances in films like Hallelujah!

READ THIS: Nina Mae McKinney: The Black Garbo

Mary Bowser

Not many enslaved young women got sent to boarding school to be educated, but smart, resourceful Mary Bowser was lucky enough to be born on a Richmond plantation owned by a staunch abolitionist who not only appreciated Mary’s talents but wanted to help her develop them. When the Civil War started, Mary’s former owner risked her life to start a spy system to pass information to the Union Army. Mary was one of her recruits. The fact that she was both Black and a woman made it easy for Mary to fly under the radar when she was hired as a servant for Jefferson Davis. Assuming Mary was ignorant and illiterate, Davis had confidential conversations in front of her and left official papers where she could see them. Though Davis suspected a leak, it wasn’t until late in the war that any suspicion fell on Mary.

READ THIS: Mary Bowser and the Civil War Spy Ring

Homeschool Unit Study: The Harlem Renaissance

Black History Month is the perfect excuse to celebrate the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African-American culture that lit up the creative landscape of the 1920s with its epicenter firmly located in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood.

Black History Month is the perfect excuse to celebrate the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African-American culture that lit up the creative landscape of the 1920s with its epicenter firmly located in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood.

Jacob Lawrence, 1917-2000, To Preserve Their Freedom, from Toussain L'Ouverture series, serigraph, 1988-1997. Museum of Arts & Sciences, Daytona Beach.

The Harlem Renaissance is one of my favorite periods of U.S. history to explore in our high school homeschool. My students get excited by the sheer abundance of possibilities: You’ve got art, you’ve got literature, you’ve got music, you’ve got social criticism, you’ve even got food. On apparently every front, Black Americans were bringing their culture and creativity into play, and the result is almost an embarrassment of riches. There are several directions you could go with this unit: Treat it as a literature unit, and dive into some of the period’s most important works, or use it as a jumping-off point for a big, interdisciplinary study of early 20th century African American history. We usually do the latter, since the Harlem Renaissance also provides an impetus and meaningful background for the civil rights movements of the mid-20th century.

READ

Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois

The sociologist and activist W.E.B DuBois was in many ways the father of the Harlem Renaissance, and in this, his most important work, DuBois makes a claim for re-thinking of African-American identity that was to resonate with a generation of African-Americans. DuBois was himself a remarkable figure — the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University, he wrote many books, founded the Niagara movement, which opposed Booker T. Washington’s policies of conciliation, and fought for the rights of African-Americans to vote and enjoy the same privileges as other Americans. Souls of Black Folk memorably and movingly describes DuBois’ dawning awareness of his “double consciousness” as an African-American, “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

“The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” by Langston Hughes

One of the central debates of the Harlem Renaissance was the question of what art, specifically African-American art, was meant to do. Should the concern of black artists be to counter white stereotypes or simply to portray black life as realistically and authentically as possible? While DuBois thought the former, a younger, more militant generation of black artists, most prominent among them the poet and novelist Langston Hughes, aimed to show all of Black life in their art. In this essay, published in the Nation magazine in 1921, Hughes criticizes those middle-class Blacks who are ashamed of their race and calls on African-Americans to embrace their own heritage and “indigenous” art forms, such as jazz.

Cane by Jean Toomer

Blending poetry with sketches of black life in the South and North, Toomer’s Cane is one of the literary masterpieces of the Harlem Renaissance. Toomer was a racially mixed man who could pass as white and, according to Henry Louis Gates and Rudolph P. Byrd, often chose to.

Every Tongue Got to Confess: Negro Folk-Tales From the Gulf States by Zora Neale Hurston

Though best-known for the classic (and staple of high school English curricula) Their Eyes Were Watching God, Hurston began her career carrying out anthropological field work in the South. This collection of her sketches from her travels in Florida, Alabama, and New Orleans show how central the African-American experience in all parts of the United States, not just in Harlem, were to members of the Harlem Renaissance

LOOK

Carl Van Vechten

Van Vechten was one of the most unusual figures of the Harlem Renaissance. A prototype of what Norman Mailer would later call the “White Negro,” Van Vechten saw himself as a champion of African-American culture, and though his involvement in the movement was controversial, he was instrumental in bringing the work of African-American writers and artists to a wider public. A novelist, dance critic, and Gertrude Stein’s literary executor, he also photographed many of the Harlem Renaissance’s prominent figures, including DuBois and Zora Neale Hurston.

Aaron Douglas

The visual arts were central to the Harlem Renaissance, and Douglas’s African-influenced modernist murals caught the attention of the leading intellectuals of the movement like Alain Locke and W.E.B DuBois. Douglas’s best-known work were the illustrations he created for James Weldon Johnson’s books of poetic sermons, God’s Trombones.

LISTEN

“Prove It On Me Blues” Ma Rainey

Big, bold, and fearless, Ma Rainey was one of the first female blues singers to achieve fame. Though she didn’t have a great voice, Rainey delivered the double entendre-laden lyrics of her songs with a power and intensity that paved the way for later female singers like Bessie Smith. Here, Rainey sings in remarkably bold terms about her romantic pursuit of a woman, and of her preference for lesbian relationships. The theme of homosexual love was central to the Harlem Renaissance, the historian Henry Louis Gates even arguing that the movement “was as much gay as it was black.”

“T’aint Nobody’s Business if I Do” Bessie Smith

More than any other singer, Bessie Smith embodied the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance — its emphasis on race pride, its uncompromising view of the value of African-American lives.

“Black and Blue” Louis Armstrong

Originally written by Fats Waller for the musical Hot Chocolates, “Black and Blue” became, in Louis Armstrong’s hands, a defiant statement on what it was like to be black in America (Ralph Ellison riffs poetically on the song in his great novel Invisible Man.)

WATCH

The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross

Henry Louis Gates’ sweeping survey of African-American history provides a good general background to the movement and his section on Black popular arts and film of the 1920s is particularly helpful.

Against the Odds: Artists of the Harlem Renaissance

Focusing mainly on the visual arts, this documentary shows how art and politics were inextricably linked for members of the Harlem Renaissance.

Langston Hughes’ “The Weary Blues”

Jazz cadences and rhythms can be found throughout the poetry of Langston Hughes and in this spoken reading, Hughes reads his own poetry to jazz accompaniment, from a broadcast of The 7 O’Clock Show, 1958.

A Note About Affiliate Links on HSL: HSL earns most of our income through subscriptions. (Thanks, subscribers!) We are also Amazon affiliates, which means that if you click through a link on a book or movie recommendation and end up purchasing something, we may get a small percentage of the sale. (This doesn’t affect the price you pay.) We use this money to pay for photos and web hosting. We use these links only if they match up to something we’re recommending anyway — they don’t influence our coverage. You can learn more about how we use affiliate links here.